A Presidential Palace, a Haunted Rolls Royce, and a Historic Election in Haiti

“This place needs a fresh coat of paint,” Mike said to me as we stood in the flag-bedecked United Nations Square in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Mike, my executive officer, was the king of dry wit. Besides his sense of humor, Mike was a superb executive officer, and I wouldn’t meet his equal until years later when another snarky “minion” named Bryan kept me laughing through a year in Kabul, Afghanistan. Of course, in the grand tradition of the Army’s “small world continuum,” Bryan and Mike, both retired from the military, worked together until recently. Oh, to be a fly on their connecting cubicle wall. But back to our story.

Newly installed Haitian President René Préval gives his inauguration speech. Photo courtesy of the author.

Mike was right. After decades of turmoil—corrupt and dictatorial regimes, violence, gangs, natural disasters—Haiti couldn’t seem to catch a break. Yet on this day, Feb. 7, 1996, the nation seemed to be turning a corner.

Mike and I stood across from the Palais Legislatif checking out the preparations for the installation of René Préval as the new president of Haiti and its first-ever peaceful, democratic transition of power.

We’d arrived in Haiti the previous fall as part of the United Nations Mission in Haiti. By now, my medical company from the 101st Airborne Division had been here more than four months providing medical support out of three small base camps around the country: Les Cayes on the southwest peninsula, Gonaïves in the central part of the country, and Cap-Haitien, in the north. We were part of a medical task force attached to the 131st Field Hospital in the industrial area just south of the international airport. After the successful elections two months earlier, those various base camps started closing. No longer needed, my platoons gradually moved back to Port-au-Prince where they joined my small command team in the cramped warehouses we called home.

Today, I had teams supporting three sites around the city. The first was around the corner from where Mike and I stood, just behind the Palais Legislatif where the Haitian Parliament met. A second team of medics was just outside the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de L’Assomption, and the third at the Palais National, commonly known as the Presidential Palace. Each of these locations had inauguration events, including the formal swearing-in ceremony and celebration of a Mass to bless the change in leadership.

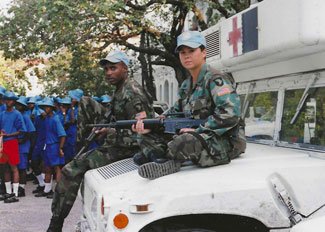

Soldiers from C/426 FSB, 101st Airborne, supporting Haiti’s inauguration day ceremony. Photo courtesy of the author.

As we wandered around, the square quickly filled up with Haitians and foreigners alike, all there to witness the historic event. The news media were out in full force, with heavyweights like Agence France Press and CNN positioned to capture the details. Despite tight security that included a cordoned-off area and sniper positions on neighboring roofs, a large, celebratory crowd gathered. There were a few protesters too, including one older man dressed in red and blue animatedly waving his fists about something he clearly cared deeply about.

To us, it all seemed pretty amazing.

As the swearing-in approached, Mike and I sat directly outside the shuttered windows of the very room where Aristide transferred the presidential sash to Préval, and I snapped some halfway decent photos of the new president. It was surreal to be witness to the event from such close proximity, especially as a relative nobody.

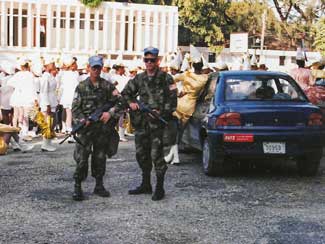

Former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, third from the right, leaves the Palais Legislatif. Photo courtesy of the author.

As the ceremony ended, we had a great vantage point from which to watch the old and new presidents exit the palais, enter their limousines—in Aristide’s case, a dodgy-looking early ’90s blue Chevrolet Caprice Classic that I did not expect—and drive off to the cathédrale for the inauguration Mass.

We released the first team to go back to the industrial area and the hospital, hopped in our white HMMWV, and drove to the cathédrale to make sure our team remained alert and ready. Finding everything under control, we hung around with them while Mass went on inside the beautiful and immense white-and-pink church.

After an uneventful hour and a half or so, Mass ended, and we proceeded to the final spot where we had a team, the Palais National. Here, in addition to checking the troops, the platoon leader, a second lieutenant named Katie, showed us around. For some reason, we had access to the roof, and we went up and quickly took a few photos—with real film cameras since there was no such thing as fancy cell phones or selfies back then.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

“Sir, do you want to see something really cool?” Katie asked after we descended.

I am all about things that are cool. “Absolutely,” I said, wondering what could be cooler than hanging out on the Haitian president’s roof.

“OK then. … Follow me.” She led us out of the building and to the car park in the back. There, under a layer of dust in the dim recesses of the garage, was the allegedly haunted Rolls Royce Silver Shadow limousine that once belonged to the dictatorial Duvalier family.

The “haunted” Rolls Royce that belonged to François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Photo courtesy of the author.

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier served as president of the Republic from 1957 to his death in 1971 and is primarily remembered for his personal death squad, the Tonton Macoutes, his embrace of traditional Haitian vodou, and his cult of personality. He even rewrote the Lord’s Prayer to say, “Our Doc, who art in the National Palace …”

Duvalier once had the head of a guerrilla conspirator cut off so he could use his occult powers to divine information about plots against him. So, not really a great guy. Seeing his personal limousine felt super creepy. I don’t know about you, but I’m not sure what to think about ghosts and other haunted stuff. I’m sure I don’t want anything to do with such things. Heck, when we lived in Japan, my wife, who was also in the Navy, made me go watch Ju-on (The Grudge) at a Halloween party. Afterward, whenever she was out to sea on the USS Kitty Hawk, I’d never even look at the tatami closet in our home, lest the Ju-on girl come crawling out of it.

Have you ever been someplace that just had an unsettled feeling in the air? The palace was one of those places. Thoroughly creeped out, I snapped a quick picture of the car, hoping not to get any Papa Doc residual bad juju on me, checked my watch, and said, “Oh, golly! Look at the time! We’ve got to get going!”

“Goodbye, Titid, See You Soon,” mural, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Photo courtesy of the author.

After making my excuses, we headed back to the industrial park where we gave a quick after-action review to the hospital commander and called it a day. And what a day it had been. The first-ever peaceful transition of power between Haitian presidents. Not that we had a lot to do with it in any sort of direct way, but being there, seeing the process unfold, and actually witnessing history up close felt significant. Never before or since have I witnessed, from 50 feet away, such a historic moment—or stood on the roof of a palace and peeked inside a haunted Rolls Royce, for that matter.

Yet despite that historical bright spot—and the hope it inspired—Haiti’s story remains turbulent, even tragic.

In 2010, a massive earthquake killed more than 200,000 people and displaced more than a million. Palais National and Cathédrale Notre-Dame de L’Assomption were casualties of that catastrophe and, some 14 years on, are not yet restored and may never be. In 2012, the country suffered the worst cholera outbreak in history, claiming nearly 10,000 lives. In 2021, another earthquake rocked Haiti and its last elected president was assassinated—an event that sent the country into a downward spiral that continues to this day.

David Fugazzatto and his executive officer outside the Palais Legislatif, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Photo courtesy of the author.

On Feb. 29, violence erupted as Haitian gangs carried out a series of coordinated attacks. Haiti’s acting President Ariel Henry resigned, and in that vacuum, one of the country’s most notorious gang leaders, Jimmy Cherizier, aka “Barbeque,” seems to have consolidated much of the power in the capital city. U.S. Marines were sent to Haiti to protect the U.S. Embassy and airlift Americans to safety.

Last week, the United Nations human rights office called the situation in Haiti “cataclysmic,” with one expert telling reporters that it is the worst violence he has seen in the country in decades.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

At the time of this writing, it is a nation in chaos, plagued by violence and now famine.

After witnessing Haiti in a relative state of peace and stability during the peacekeeping mission in the mid-1990s, this is especially heartbreaking.

It will take a lot more than a fresh coat of paint to bring it back from this latest setback.

This War Horse reflection was written by David Fugazzotto, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett contributed the headlines.

Comments are closed.