My Dad Should Have Lived a Long and Joyful Life. His Love Was Meant to Fill This World.

My dad knew two things. He wanted to serve this country, and he wouldn’t live until his 40th birthday. In 2006, his last prophecy came true. He was 36.

“On behalf of the president …” were the last words I remember hearing two uniformed officers say before my ears felt like they heard an explosion. The words left me paralyzed. I felt my heart rate accelerating. My vision slowed and blurred. My mouth went dry.

I didn’t say anything. I just froze.

I remembered what my dad, an Army intelligence officer, told me months earlier, the night before he deployed to Iraq.

“Princess,” he said with a soft smile, “I need to talk to you about something pretty serious.”

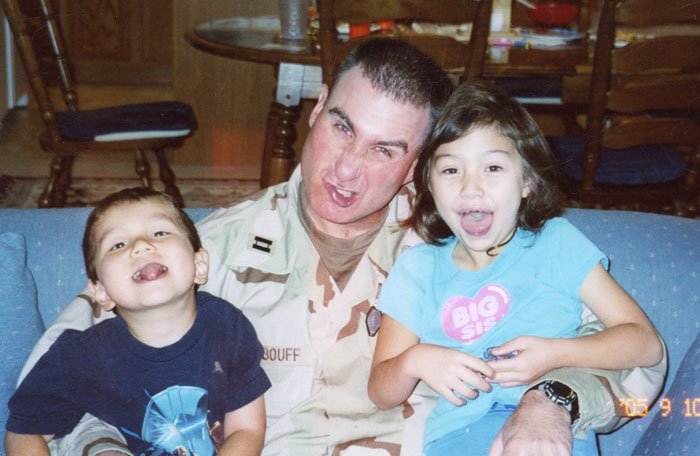

Douglas A. La Bouff with his children, Cassidy and Doug, making funny faces. La Bouff, an Army intelligence officer, was killed in Iraq in 2006 along with 11 other soldiers when their helicopter crashed. Photo courtesy of the author.

I was only six years old, all bangs and no front teeth. His tone was stern, but his voice was soft.

His eyes were the same.

“I might not come home,” he said. “If that’s the case, you have to help with the house and make sure Mom and little Doug are taken care of. Promise me.”

I didn’t say anything. I just stood there. I understood the bigger picture—it was his turn to fight for his other great love, this country. And it was our turn to give him to this country we love.

* * *

It was the last Saturday of Christmas break in January 2006, and I’d slept in later than usual. In the night, I’d dreamed my family and I were in a plane crash in the mountains. My mom, brother, and I were strapped in our seats, but Dad was nowhere to be seen. I screamed for him, but there was no response.

Then I woke up. It took a long time to fall back asleep.

The sun was out as I walked downstairs, and I noticed that it had melted the snow enough to play on the swing set. Mom, Grandma, and Doug had just finished breakfast. Doug returned to his pile of Christmas gifts. I went to put on my favorite Disney album.

Knock. Knock.

Our front door has two glass windows in the middle, and there they stood, two officers in blue. Their jackets were crisp, and they wore berets slightly tilted over their left eyes with badges that gleamed in the sun. Their faces gave away nothing—a stark contrast to my mother’s guttural cry.

It sounded like a knife scraping across a chalkboard. Her body sank to the floor. She could not get herself up to open the door.

The air seemed to vanish from my lungs.

My first clear thought in those awful moments was to “suck it up,” a phrase Dad often used in our household.

At some point, the door was opened. Helicopter crash, I heard them say as I sprinted to find my brother.

I didn’t want to hear the rest. Maybe it wouldn’t be real if they didn’t finish the story. Maybe I was still trapped in my nightmare.

U.S. Army Maj. Douglas A. La Bouff died in January 2006 when the UH-60 Blackhawk he was in crashed in Northern Iraq. Photo courtesy of the author.

It seemed like our house was immediately packed full of friends and family, a sardine can of military brass and their obligatory condolences.

“We are so sorry for your loss. … ” The words bounced from wall to wall, over and over. Friends from church said it. Our neighbors from down the street said it. People from the base. It seemed that was all they could think to say.

Through the crowd, a little blue swing caught my eye—my brother Doug outside. That’s when it hit me.

Dad would never get to see him grow up.

This was our new reality. Watching life go by without him standing next to us.

I am now the protector.

I promised Dad.

Grief is a running joke. Sometimes it lands, sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it leaves you laughing, and then sometimes, it leaves you in tears. And if it lands on target, it’s a mix of all these.

Cassidy La Bouff and her dad, Maj. Douglas A. La Bouff. Photo courtesy of the author.

My mom, after the initial inertia, did not miss a beat. Her days without him consisted of early mornings straightening out the house, getting us to school and after-school activities, and going to her classes. After Dad was gone, she decided to finish her degree. When the lights were out, when everything else was done, she turned on one small lamp and did homework.

She finished her undergraduate degree in two years while grieving and caring for her kids. She said we saved her, but we all know she saved us.

I ran through the motions, checked days—and then months and years—off like items on a grocery list.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Seven. My classmates talk about their dresses for the father-daughter dance at church. They ask me what I’m going to wear. I have no answer. I’m not going to the dance. No one wants to talk about Dad, but I long to.

Twelve. I’m mad all the time. I’m falling behind in class. The doctor’s diagnosis: trauma and dyslexia. I feel stupid, incurable.

Fourteen. I’ve lived longer without him than with him. I am always in a state of anxiety. Always waiting for the next shoe to drop.

Twenty. I’m selected to attend a career symposium with a military nonprofit. For the first time, I cross paths with another Gold Star child, and this is a turning point. My world—gray for so long—is now tinged with color. And for the first time since that morning when the uniformed men approached our door, I feel air in my lungs.

Everything that came before led me to this moment, and I have the feeling that I am exactly where I am supposed to be.

Cassidy La Bouff, center, with her mother and younger brother. Photo courtesy of the author.

Three years later, I’m at the Louvre in Paris, looking at The Winged Victory of Samothrace. It is an angel made of the finest stone, intricately detailed, perfect and imperfect. I feel my heart accelerating. My throat tightens and my eyes fill with tears. Dad was a lover of history.

I wish he could’ve seen this.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

But this is not a sad story. I see and feel Dad in everything around me. I hear his laugh in my brother’s. I feel his warmth when I hug Mom. I see his courage and perseverance in my fellow Gold Star friends. I feel him guiding me through my philanthropic work. I see his self-sacrifice when the American flag waves in the wind. I feel him in my prayers, when the sun hits my face, when a baseball cracks on a bat, when waves crash on the shore, when birds sing.

I feel him now, as I gaze at this ancient sculpture.

I realize that loss no longer feels joined with sadness. This is a new feeling. This is peace.

This War Horse reflection was written by Cassidy La Bouff, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.