VA Buried Their Brother as an ‘Unclaimed Veteran.’ Now They’re Working to Bring Him Home. The remains of veterans – some dating back to the Civil War – sit neglected at funeral homes across the country.

One Saturday in March, with a few minutes to spare before choir rehearsal, Patti Pugh engaged in what had become a habit over the last two years: “One of my Alvin searches.”

In February 2022, her 60-year-old brother, Alvin Jerome Pugh, seemingly vanished. He lived in New York City, far from his siblings in Pueblo, Colorado, but he always responded to texts and calls. Suddenly, he was silent. At first, Patti, her sister, and their three brothers thought Alvin had lost his phone, but as his absence dragged on, they grew more worried.

Patti and her sister, Theresa, started contacting dozens of hospitals in New York City, including VA Medical Centers, because Alvin was an Air Force veteran.

They couldn’t file a missing person’s report with the NYPD because they didn’t have Alvin’s latest address. The family searched a database that lists missing and unidentified people. Nothing. No luck for two years.

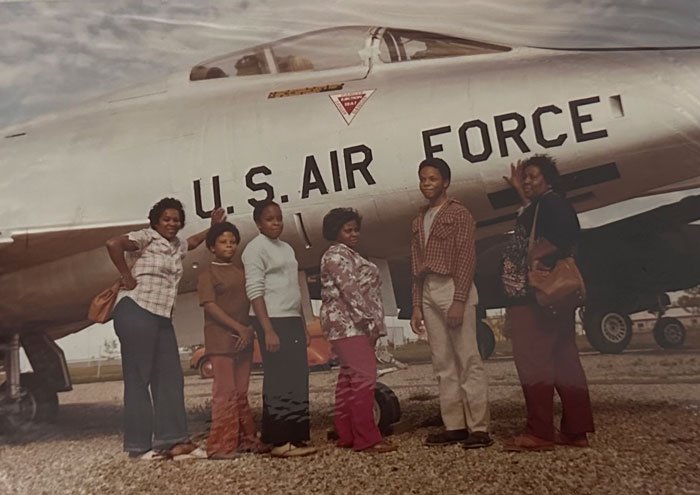

After enlisting in the Air Force, Alvin Pugh (second from right) poses with his mother to his right, aunt (far left) and sisters at the Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum in Pueblo, Colorado. (Photo courtesy of the Pugh family)

But on that morning this past March, sitting at her computer in the brick house that her father and brothers built in 1965, she Googled “Alvin Pugh” and “NYC.”

Findagrave.com popped up: Calverton National Cemetery, section 51A, site 2098.

“Oh my God,” Patti said with astonishment, “Alvin is dead.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs had buried her brother in 2023. But nobody notified his family.

Stacked on Shelves Like Forgotten Paint Cans

Disbelief gripped Patti and her siblings. Had anyone even tried to look for them? Sure, they lived 1,800 miles from New York City, but Patti, Theresa, and their brother Kennedy reside in the same house Alvin lived at when he enlisted and was honorably discharged from the military. And Alvin’s paperwork with the Veterans Health Administration even listed Theresa as a contact.

Still, somehow, Alvin Pugh mistakenly became one of the 2,300 “unclaimed veterans” buried by the VA’s National Cemetery Administration across the country last year. By law, the VA is required to ensure that deceased veterans without a next of kin receive dignified burials, with a casket or urn. Next week, a few days after Memorial Day, the unclaimed remains of 25 veterans will be buried at Tahoma National Cemetery in Washington state, their service dates ranging from the Spanish-American War in 1898 to the Persian Gulf.

Missing in America Project volunteers say tens of thousands of unclaimed veterans’ remains are piled up on funeral home shelves across the country, similar to those pictured above at a storage facility in Washington state. (Photo courtesy of Tom Keating)

But for decades, bureaucracy and a lack of coordination among the VA and local agencies has allowed tens of thousands of veterans who die alone to pile up, in funeral homes and morgues around the country, as their cremated remains linger in storage facilities, stacked on shelves like forgotten paint cans, some collecting dust for more than 100 years.

Outrage over the discovery of 28 veterans who had spent 44 years in a mortuary in Oregon spurred an Office of Inspector General investigation and promised reforms by the VA in 2021.

A year later, the search for Alvin Pugh’s next of kin began.

VA Pill Bottles Provide a Clue

When they first lost touch with their brother in February 2022, Patti and her siblings hoped it was just Alvin being Alvin—private, a little mysterious, a total prankster. A few weeks before her brother’s death, Patti was in New York for work but couldn’t connect with Alvin. He ended up leaving her a voicemail acting like a hotel manager, barking at her about stealing from her room. “I freaked out,” she recalls. “At the end of the message, I realized it was Al.”

More coverage: How a volunteer group helped provide dignified burials for 5 forgotten vets.

Alvin’s siblings knew that for more than 15 years, he had struggled on and off with drug addiction. It began after the deaths of his mother and his longtime partner. “It was really difficult on him and he got really depressed,” says his brother Kennedy.

After a few months without answers, another one of Alvin’s brothers feared he was dead.

It took years, however, to piece together what happened. His death certificate cites a pulmonary embolism as his cause of death, his sickle cell disease putting him at a high risk for blood clots. He died Feb. 2, 2022, in his apartment, and a roommate called 911.

In a phone call with the medical examiner, Patti and Kennedy learned that the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner investigator noticed VA pill bottles in Alvin’s apartment. By early March 2022, the Veterans Benefits Administration had confirmed that he drew a monthly pension of $1,229 and that he qualified for burial in a national cemetery.

Members of the Connecticut Army National Guard Funeral Honors Team, and a veterans service organization member prepare to inter the cremated remains of eight unclaimed veterans at State Veterans Cemetery in Middletown, Connecticut, on Oct. 1, 2021. (Connecticut National Guard photo by Maj. David Pytlik)

In that same call, the Pugh siblings learned that the medical examiner office’s search for next of kin included calling Alvin’s phone to see if anyone would pick up. No one answered. They searched New York City public records and turned up a caseworker who worked with Alvin, but she didn’t return the office’s calls. Ultimately, Alvin was labeled “unclaimed.”

No one from the New York City medical examiner’s office responded to multiple phone calls and emails from The War Horse about Alvin’s case.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Without a relative coming forward, the VA took custody of Alvin’s remains. That’s why when Patti combed through Namus, a Department of Justice database listing missing and unidentified people, he didn’t appear.

So on Feb. 21, 2023, a year after his death, on a chilly, wet day, Alvin Pugh was given a “dignified burial” at Calverton National Cemetery in New York, according to VA spokesman Terrence Hayes. Halfway across the country, his family remained oblivious for another year.

Two generations proudly served

Hayes acknowledged that the VA never checked Alvin’s VA records, which listed his sister as a contact. If Alvin had died in a VA Medical Center, there’s a greater chance she would have been notified. But when veterans die alone on the streets or at home, the VA depends on local funeral homes, coroners, and medical examiners to complete next-of-kin searches, says Hayes, adding that state and local laws determine how thorough those efforts should be.

Every agency that handled Avlin’s remains has told Patti they followed protocols.

“I think we are in a mode where people are just trying to cover their ass,” she told The War Horse one recent afternoon in a phone interview.

Even a little Googling, she believes, likely would have uncovered Alvin’s family—the only Black family in Pueblo with the Pugh name, not to mention a family with deep military service.

Alvin Pugh (standing in red shirt) escorted his uncles George and Charles Pugh, brother (also standing), and father, Herbert Pugh (seated, right) to a 2013 honor flight trip to Washington, D.C. (Photo courtesy of the Pugh family)

Alvin’s late father, Herbert, lied about his age to join the Army during World War II at 14, his military records and birth certificate show. Two uncles also served. And then there was Alvin, who announced he was joining the Air Force in 1981 at the age of 20. He served in Germany and the Persian Gulf, earning achievement medals for his work in intelligence and the rank of staff sergeant before separating with an honorable discharge in 1995.

“This was an amazing man, an amazing veteran,” Patti says.

Alvin felt pride as a veteran, Kennedy says, and the two accompanied their father and uncles on a 2013 honor flight to Washington, D.C. In a photo from the trip, their father, who fought in the Battle of Normandy, wears a World War II cap as he sits at a meal. Alvin stands nearby, with a muted version of his signature beguiling grin. A decade after this photo, Alvin would be buried. Unclaimed.

“Part of the way this all went down,” Kennedy says, “It feels like he didn’t matter.”

Tens of Thousands of Veterans Remain ‘Unclaimed’

Hayes, the VA spokesman, told The War Horse in an email that “we deeply apologize” for not notifying the Pugh family before Alvin’s burial. “We are taking steps to prevent this from happening again in the future.”

Calverton National Cemetery, where Pugh lies, is among the newer national cemeteries, created in the late 1970s. The first cemeteries date back to the start of the Civil War. For decades, the Army coordinated burials, and in 1973, the Department of Veterans Affairs took over most interments.

On November 14, 2022, the Missing in America Project honored 99 unclaimed veterans in Washington state. A few days later, the veterans’ remains were laid to rest at Washington State Veterans Cemetery in a service with full military honors. (Photo courtesy of Tom Keating)

But for decades, there was no clear sense of how many unclaimed remains had accumulated in need of a final resting place.

Finally, in a 2018 report to Congress, the VA estimated that 11,500 to 52,600 veterans may be unclaimed at funeral homes nationwide, a sprawling numerical range that didn’t even include remains held by county coroner or medical offices.

Until April 2023, no office within the VA was responsible for the burials of all those unclaimed veterans. The VA’s Pension and Fiduciary Service Office is now in charge.

They’ve created a central database to track burials of unclaimed veterans in national cemeteries, and they’ve hired coordinators throughout the country to search the entire VA system to find a next-of-kin contact.

The VA recently surveyed funeral homes and counted 21,000 unclaimed deceased veterans.

Don Gerspach, director of the Missing in America Project, says that number seems low. There’s “probably 100,000 or more out there,” says Gerspach, whose nonprofit has located and identified unclaimed veterans and provided thousands of proper burials since 2007.

Looking for a lost veteran in your life? Tell us your story by emailing lostveterans@thewarhorse.org so we can investigate or connect you to volunteers who might be able to help.

Gerspach says it’s tedious work identifying unclaimed veterans stored for years in back rooms and storage facilities, and his nonprofit relies on a network of volunteers who act as detectives, relying on public records, VA paperwork, and, if lucky, relatives to confirm a veteran’s service.

While DNA is often used to identify the remains of service members killed or missing overseas—like a 19-year-old sailor identified last month who died during the attack on Pearl Harbor—it isn’t used with veterans who are unclaimed at morgues and funeral homes across the U.S. Many of them were cremated.

The longer veterans’ remains stay on shelves, the more challenging the work. Most of the 6,500 veterans the nonprofit has buried served between World War I and the Vietnam era, Gerspach says, though some date back to the Revolutionary War era.

Veterans like Alvin Pugh, who are mistakenly labeled “unclaimed,” happen occasionally, Gerspach says. Mostly, though, they have lost all ties to family.

Patriot Guard Riders and other veterans groups supporting delivery of cremains to the Washington State Veterans Cemetery. (Photo courtesy of Tom Keating)

Tom Keating, the nonprofit’s Washington state coordinator, recalls talking with a funeral director who was turning over the cremains of an unclaimed decorated Vietnam veteran. When Keating asked if the family had been contacted, the funeral director told him that the family advised to “flush him.”

Gerspach, who lives in Missouri, says the biggest hurdle in getting the tens of thousands of unclaimed veterans buried is that some funeral homes won’t turn over remains. “In fact there are two [funeral homes] here in St. Louis who won’t give us access,” he says. “And we’ve identified six veterans in their care.”

Jessica Koth, director of public relations for the National Funeral Directors Association, says some homes “fear they would be held civilly or criminally liable if they are not able to reunite” the remains with family should they pop up in the future, even though many states have laws that protect funeral homes, as long as good faith efforts were made.

In Washington, though, Keating and his fellow volunteers are busier than ever. A funeral home that merged with other homes is trying to clear out more than 3,700 unclaimed remains from a storage facility with urns packed onto wooden shelves, floor to ceiling. So far, Keating has identified 200 veterans from this site, some dating back to the Civil War.

Bringing Alvin home to Colorado

Now, the Pugh family has one goal: bring Alvin home.

In mid-April, they held a funeral mass in Pueblo, Colorado, even with Alvin’s body still interred in New York.

Pews filled with longtime family friends. Kennedy spoke of Alvin’s wit and resilience. Patti played the piano, ending the mass with “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” a patriotic song written by an abolitionist during the Civil War, and the one song Alvin learned to play on the piano.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Patti wants her brother’s remains exhumed and reburied at Pikes Peak National Cemetery north of Pueblo. In April the VA emailed Patti forms to begin the disinterment. On Wednesday, after weeks of inquiries from The War Horse, the VA informed the Pugh family it would cover all the costs to bring Alvin’s body back to Colorado.

Patti welcomed the news, but she still can’t believe what it took to find Alvin.

“I would put my life on it,” she says, “that there are other people this has happened to.”

Two months after discovering her brother is gone, she is unable to sit with her grief. It hovers, unsettled, awaiting release.

“I think it will bring closure for me,” she said, “when he’s finally home.”

This War Horse investigation was reported by Anne Marshall-Chalmers, edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.