US Army, Navy reduce dependence on China for ‘critical technology’

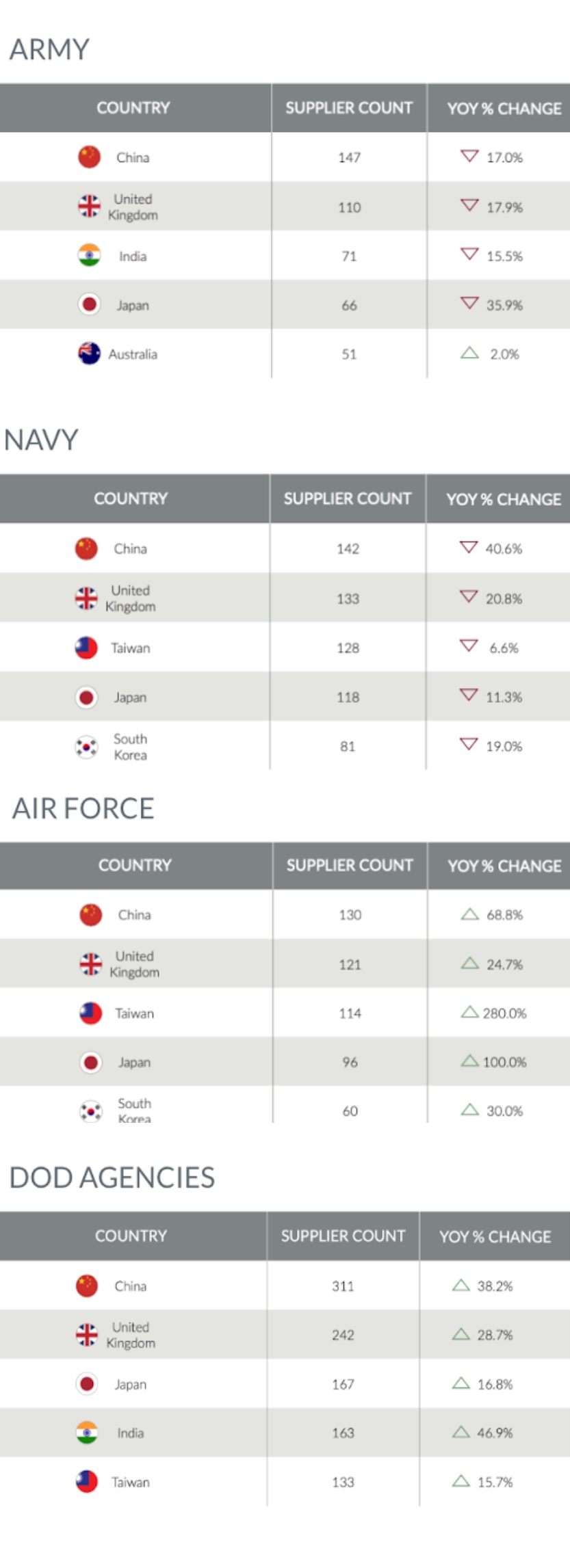

Last year, the U.S. Navy reduced the number of Chinese suppliers in its “critical technologies” supply chains by 40 percent. The Army achieved a 17 percent reduction from 2022 to 2023. But the Air Force and defense agencies increased their dependence on China, according to a new report by a government-data analysis company.

“When we’re working with these program offices on a day-to-day basis, it remains just problem after problem after problem. And I think the good-news story is that…the department, in places, in certain spots, is really starting to become proactive about managing their supply chains,” Tara Murphy Dougherty, Govini’s chief executive officer, told reporters Wednesday, ahead of the report’s release.

The report, built with Govini’s Ark data-analytics platform, looked at Pentagon purchases of 15 so-called critical technologies: biotechnologies, data interfaces, nuclear modernization, space, communications and networks, engines, advanced manufacturing, robotics and autonomy, advanced engineering materials, AI and machine learning, hypersonics, clean energy and storage, microelectronics, advanced computing, and directed energy.

Since 2018, when Congress passed a ban on China-made communications technology, Pentagon leaders and lawmakers have been pressing Defense Department components to reduce their dependence on Chinese-made components and gear as part of an effort to develop more resilient supply chains.

“We know we’re never going to get China fully out of U.S. supply chains,” said Murphy Dougherty. “That’s not even the goal, but managing the presence of lots of different foreign suppliers and aligning those to the right level of capability or component or parts, making sure we have redundancy where we need it and that the most sensitive parts are fully protected and coming either directly from the United States or from friends and allies is really what the call to action is.”

Murphy Dougherty said she was surprised at the military departments’ progress, but said there was room for improvement.

“When you look at the set of foreign countries that appear in defense supply chains—and really, U.S. government supply chains—China is the most prominent and contributes the most even at incredibly high levels of the supply chains. These are not, you know, buried-down core components that don’t matter. These are as high as suppliers at the tier one level,” Murphy Dougherty said.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the fragility of U.S. supply chains and a disproportionate reliance on China-based suppliers for weapons. However, in the past four years, supply chain challenges have somewhat stabilized but still remain high on defense companies’ list of concerns—whether it’s parts or cybersecurity.

Earlier this year, the Pentagon released its first strategic document for defense contractors, followed by a cyber-focused strategy, both of which stressed supply chain security and risks.

But some defense officials don’t want to hear suppliers blame supply-chain woes for program delays or cost overruns.

“I have seen a lot of smaller space companies have absolutely no issues with supply chain. I see it more fundamentally in our bigger primes that whine about supply chain, and I think they are the ones that have the resources and the assets to actually do something about it and actually be smarter,” Frank Calvelli, Space Force’s acquisition chief, said in February. “Buy your parts early, get your orders in, be organized, be effective. But yeah—I can’t stand when they come in and say supply chain or COVID is why they can’t meet their schedule. I think it’s a lack of planning why they can’t meet their schedule.”

But there could also be a lack of cohesive policy, Murphy Dougherty argues.

“Even if it’s just OSD coming out and saying, ‘We’re not going to centralize the approach and we want the services to figure out what they’re each going to do, and then the services say we’re gonna let the program offices do it.’ Whatever the approach is, give us an answer. And that’s been lacking, which means you still have programs who aren’t doing anything to turn that corner,” she said. And “when it’s too late to do anything about it. The program inherits that challenge, and then it impacts production and ultimately availability.”

CHART: Foreign suppliers of “critical technologies” components by service in 2023

Comments are closed.