What the Assange saga says about the state of the American empire

US allies have cravenly capitulated before Washington’s demands for the journalist’s blood, but his ultimate release is a ray of hope

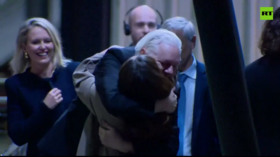

This week prominent journalist and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was freed from a UK prison after striking a plea deal with US authorities and President Joe Biden.

The deal involved Assange pleading guilty to one charge of conspiring to obtain and disclose national defense information under the US Espionage Act – 17 other charges under the act were dropped – and then being pardoned by President Biden.

After being released from Belmarsh prison, Assange was immediately flown by chartered jet to the US-controlled Pacific island of Saipan in the North Mariana Islands, where he appeared before a US District Court judge and formally entered his guilty plea.

Assange, an Australian citizen, then flew back to Australia, thereby ending (for the time being at least) the saga that commenced in October 2010, when WikiLeaks published reams of classified material relating to US involvement in its ill-judged and disastrous wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

That classified material had been leaked to Assange by Chelsea Manning, a former US soldier, and its publication seriously embarrassed Washington and the US military.

The leaked material revealed, amongst other crimes and questionable activities, that the US military had killed unarmed civilians in Iraq (the infamous “collateral murder” video) and that the US had regularly spied on United Nations leaders.

The US – outraged at having its nefarious activities exposed – responded by conspiring to have trumped-up sexual assault charges brought against Assange in Sweden, with a view to having him extradited to America after he was convicted.

Assange responded by handing himself over to authorities in London, and commenced proceedings in the UK courts to avoid being extradited back to Sweden.

In June 2012, Assange skipped bail and sought refuge in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where he remained a virtual prisoner for the next seven years.

In 2017 the Swedish charges were dropped, and in 2018 Assange was formally charged by the US Department of Justice – thereby triggering his protracted battle in the UK courts to avoid being extradited to the US, which only ended this week.

In April 2019, Assange left the Ecuadorian Embassy and was taken into custody by UK police and imprisoned for having breached his bail conditions in 2012. He remained in prison in London until he was released earlier this week.

The Assange saga is a salutary tale about the exercise of US power as the American Empire declines, and the continuing willingness of US allies like the UK and Australia to comply with America’s demands – even when they involve persecution of citizens of those allied countries.

Assange’s release is understandably being portrayed by some commentators as a victory of sorts – the international Federation of Journalists called it “a significant victory for media freedom” – and insofar as Assange has regained his personal freedom, it is.

But it should not be forgotten that for the past 14 years the US has been able to successfully – with the abject complicity of governments and authorities in the UK and Australia – imprison a journalist of international stature for simply engaging in genuine investigative journalism.

Assange is a journalist – not a whistleblower or leaker of classified material. Nor did Assange’s publishing of the classified material in question cause any real harm to the US – other than to embarrass it by disclosing the truth about American conduct during its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

America’s fabled commitment to freedom of speech and the press – embodied in the first amendment to its constitution – has never been absolute, but, as the Assange saga clearly shows, it has probably never been weaker than over the past few decades.

That is not surprising – given that pursuing the inherently corrupt aims of the Empire overseas must inevitably result in the curtailment of domestic freedoms.

Barrington Moore Jr described this relationship as “aggression abroad and repression at home” during the height of the Vietnam war in the late 1960s, and America’s founding fathers were well aware of how the British had been corrupted by their Empire.

Washington in his farewell speech warned against America becoming involved in “foreign entanglements” – and John Quincy Adams famously said “America goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all.”

And Edmund Burke, the conservative 18th-century British statesman, and stern critic of British policy in America and India, pointed out that “the breakers of the law in India are also the makers of the law in England.”

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the US persecution of Assange should have occurred during a period in which America has engaged in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and promoted and funded proxy wars in Gaza and Ukraine.

And there can be no doubt whatsoever that if Assange had been extradited to the US and had been tried in an American court, that he would have received a very lengthy jail sentence. One prosecutor suggested that a term of 175 years would have been an appropriate punishment for him.

Nor should it be forgotten that America’s persecution of Assange was carried out on a bi-partisan basis. Mainstream Democrats and Republicans were equally keen to put Assange in prison. Hillary Clinton was a particularly rabid critic of Assange, as was Biden until very recently. In fact, Donald Trump had a measure of sympathy for Assange because WikiLeaks had published the emails that had damaged Clinton’s reputation in the lead-up to the 2016 election.

America’s internal decline over the past 50 years can be gauged by comparing Assange’s likely fate with what happened to Daniel Ellsberg – who famously leaked the Pentagon Papers to the Washington Post in the early 1970s. When Ellsberg was prosecuted, the US courts threw the case out on the basis the Nixon administration had subjected Ellsberg to unlawful persecution.

Equally troubling – especially for the citizens of the UK and Australia – is the fact that, until very recently, governments in both of these countries cravenly capitulated to US demands in relation to Assange.

Here in Australia, the conservative government that was in power until 2022 refused to do anything at all to support Assange for a decade. And it was only very recently that the Albanese Labor government began negotiations with the Biden administration to arrange for Assange’s release.

In the UK, the Conservative governments have shown little or no interest in the Assange saga – and were content for the matter to be dealt with by the courts. Nor has Kier Starmer’s Labour Party supported Assange – although Jeremy Corbyn, to his credit, did so.

And, until very recently, the UK courts have consistently ruled against Assange. That approach changed earlier this year when the UK Court of Appeal granted Assange leave to appeal from his latest adverse decision and evinced a belated interest in ensuring that Assange would be able to rely upon first amendment rights if extradited and tried in an American court. Assange’s appeal was due to be heard early next month.

It appears that the plea deal struck this week may have come about as a result of President Biden’s desire to avoid the Assange saga becoming an election issue – apparently the perpetually-confused leader of the tottering American Empire is particularly keen to retain the support of the younger radical wing of the Democratic Party who have supported Assange for some time.

Here in Australia the reaction to the Assange plea deal by conservative politicians and media outlets has been predictable – condemnation of Assange for having dared expose the truth about American war-mongering and endangering the precious American alliance, coupled with strong criticism of Biden for having settled the matter for anything less than Assange rotting in an American prison for the rest of his life.

Nothing less could be expected from these people, however, perpetually trapped, as they are, in their quasi-Cold War world view – willing to justify anything that America does on the world stage, including what is happening in Gaza; demanding increased support for the failing regime of Vladimir Zelensky in Ukraine; and trying to sabotage Australia’s recently improved relationship with China.

One optimistic aspect of the end of the Assange saga it is that such conservative interests in the US, Australia, and the UK, have ultimately not succeeded in their persecution of Assange – and that their failure was in large part due to the widespread public protests and campaigns supporting Assange that have taken place in many countries over the past 14 years.

Assange’s release is also perhaps a further sign that the power of the American Empire is continuing to wane.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

Comments are closed.