We Talk a Lot As a Nation About Service Members and Veterans. What We Don’t Do Well Is Include Them. Gestures of support for military families often miss the mark.

Andrew waited long enough to be born a North Carolinian. After weeks in an Extended Stay America in Jacksonville, North Carolina, our family finally got a move-in date for our tiny base house—and the belongings we’d long been parted from moved back in with us.

As the sky darkened on a late July day spent almost entirely on my swollen feet, I waddled down the staircase from the girls’ room and mentally prepared for the next day. Boxes to unpack. Groceries to buy. We would start with the kitchen and go from there. Now that we’d made it into the house, I needed to pack a hospital bag too. I reached the third step from the bottom, and I knew.

Andrew Suttee was born into a Marine Corps family in North Carolina two years before 9/11. (Photo courtesy of the author)

My third child, Andrew, reported for duty at 6:39 a.m., 10 days early and on day two in our new home. He arrived six months before Y2K, joining a peacetime Marine Corps where deployments were for training, not combat. That would soon change, but he would never remember the time before.

We moved to Virginia when Andrew was two years old and then on to Australia when he was five, returning to North Carolina three times before he entered high school. I would say he’s Tar Heel born and bred, but he would not like that. He’d decided as a young teenager, standing in the sports team section of our local Kmart, that he preferred the Wolfpack red of North Carolina State University to the distinctive Tar Heel blue of its rival.

Now, after three more moves, my husband Lee and I have claimed North Carolina as our forever home following 35 years of dutifully obeying orders. Andrew, now grown, lives with us while he continues his studies as a graduate student in international affairs at North Carolina State University. Lee, newly retired, encouraged Andrew to apply for a scholarship through the North Carolina Department of Military and Veterans Affairs earlier this year to help pay for it.

The North Carolina Scholarship for Children of Wartime Veterans has two eligibility options for residency: The veteran must be a legal resident of North Carolina at the start of service, or the veteran’s child had to be born in North Carolina and to have been a resident of North Carolina continuously since birth. (A strange requirement, I think, for the child of a veteran whose military career dictated almost constant relocation.)

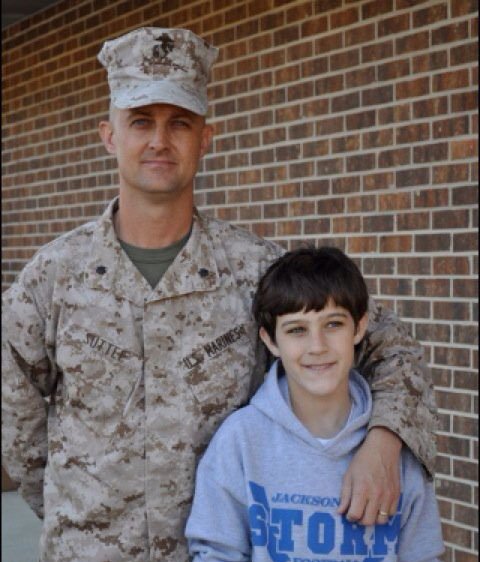

Lee Suttee with son, Andrew. Lee Suttee served in the Marine Corps for 35 years. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Lee was a resident of Oklahoma when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. So, it was on Andrew, the veteran’s child, to fulfill eligibility.

Was Andrew born in North Carolina? Yes.

Was he a resident continuously since birth? No.

Together, Lee and Andrew filled out the residency questionnaire, and Andrew hit submit.

One week later, we were sitting in the living room at my in-law’s house back in Oklahoma for a wedding. As we all settled in, Andrew, next to me on the couch, leaned over and whispered, “I didn’t get the scholarship.”

“Did they give a reason?”

“It was the residency thing.”

A couple of minutes later, I squatted next to Lee, touched him lightly on the forearm, and said, “He didn’t get the scholarship.”

Lee’s exterior remained calm as the line of his jaw tightened. He wrapped his arm around Andrew’s shoulder, speaking briefly with him before retreating to his phone, crafting, I was sure, an email.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

A quiet rage was building inside me as I looked at our now-adult kids and thought about the unnecessary struggles each had faced.

This is not about the scholarship, I thought. Of course, it is, but it isn’t just about that. It’s about being a sophomore and moving midyear to your third high school and learning the honors classes are full. It’s about being 16, thrilled to finally get your driver’s license, and moving to another state only to be ticketed for driving without a license. It’s about what it means to be a kid born into military service, the only group of draftees in an all-volunteer military.

This is also not about me. Maybe it’s not even my story to tell. My role has been to watch and support, cushioning blows, normalizing stressful things. I’m aware now that, in needing them to be OK, I probably encouraged some avoidance and denial. Their obstacle courses always seemed to include a bonus round.

Andrew Suttee, center, with his sisters, Elisabeth and Rachel. Andrew was born in North Carolina but moved away when his father, a Marine, received new orders. He returned three times before high school and graduated from North Carolina State University. (Photo courtesy of the author)

The dandelion has become synonymous with military kids. A plant with the ability to be uprooted and successfully replanted across the world. But for much of society, dandelions are invasive weeds. We can tell military kids that they are resilient and resourceful, that we value them enough to give them their very own month, but unnecessary obstacles reinforce the fact that just because you can grow anywhere doesn’t mean you’ll ever be considered a native.

For Andrew, being a resident wasn’t enough. Emails were exchanged, but ultimately the wording of the scholarship was clear. Andrew had not been a resident since birth, regardless of why, and he was ineligible for the scholarship.

One night, weeks later, as Lee stood at the sliding glass door, looking at the full moon, I sat on our couch wrestling with the thoughts that would become this essay. I went back to the scholarship website, checking for the wording, sure that it referenced the sacrifices made by military children. I was ready to write about how gestures of support, although well-meaning and intended to show gratitude, often miss the mark.

I looked up from my laptop.

“This says, ‘The North Carolina Scholarship Program was created to show its appreciation for the services and sacrifices of its war veterans.’”

I continued, “The scholarship is about veterans, not kids.”

“I’m just not one of their war veterans,” Lee said as he turned and walked past me. There was no anger in his voice, just a resigned acknowledgment of the truth.

I was sorry I had made him say it out loud.

The Suttee family in Washington, D.C. (Photo courtesy of the author)

In my righteous anger on behalf of my kids, of all military kids, I had missed the big picture. His service and sacrifice were not enough. The birthdays and first drives, volleyball games, and honor roll ceremonies, so much that Lee had missed, were among the sacrifices his service would demand when he entered the then-standing Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, some 36 years ago, raising his right hand and swearing an oath to the Constitution.

We talk a lot as a nation about service members and veterans—worshipping them, fetishizing them, and fearing them. What we don’t do very well is include them. Lee’s words repeated through my thoughts—not their veteran. I wanted to be able to argue otherwise, but it’s hard to say he’s wrong. I’m certain what he feels is not appreciation.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

In the end, I am writing about how gestures of support, although well-meaning and intended to show gratitude, often miss the mark.

Only I thought I was writing about military kids.

This War Horse reflection was written by Valerie Suttee, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.