Reunited Friends, a Missing Medal, and a Wrong Righted More than 50 Years Later

In the fall of 2000, I received a phone call from an unrecognized number with an unfamiliar area code and decided to answer.

“Is this Tigerman?” asked a voice on the line.

I thought for a second before answering.

“Is this LT?”

He knew he’d reached Tigerman, just as I knew I was talking to LT for the first time in 31 years.

Like most soldiers, I received a nickname when I joined my unit in 1968. And, as it is for most, the name endured.

I’d been drafted into the Army not long after the Tet Offensive, the first major escalation of the Vietnam War. After a brief swearing-in ceremony at the Navy base in Jacksonville, Florida, I headed first to basic training at Fort Polk in Louisiana, followed by Advanced Infantry Training at Fort Lewis in Washington. After a brief leave, I arrived at Camp Alpha and the 90th Replacement Battalion between Bien Hoa and Saigon in South Vietnam. This was a temporary assignment for soldiers to get jungle boots and lightweight fatigues and to acclimate to the tropics while waiting a few days for their in-country unit assignment.

After another stop a few miles away at Camp Frenzell-Jones, I joined my permanent unit—Alpha Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry of the 199th Light Infantry Brigade. I was assigned to 3rd Platoon, 3rd Squad. After arriving at the company, the first sergeant sent me over to the 3rd platoon area.

“This here is Lyons. He’s your new guy,” the platoon sergeant said by way of introduction.

“He don’t look like no lion to me,” the machine gunner, Steven Jensen “Groundhog,” said without missing a beat.

And so I became Tigerman.

Jerry Lyons earned the name “Tigerman” not long after arriving in Vietnam. More than 50 years later, the nickname endures. (Photo courtesy of the author)

That first night, I was assigned to drop M26 hand grenades—a standard infantry weapon—into the Saigon River under the bridge every so often. Pull the pin, drop it in, enjoy the muffled boom, and look at the bubbles, fish, and whatever else floated up. The concussion underwater, more than the shrapnel, was to deter the Viet Cong from swimming up at night to put explosives on the bridge structure in an effort to take the bridge out of service.

During most of my tour, our platoon leader was Lt. Al Watson, who’d arrived in February 1969 not long out of Ranger school. LT earned our respect right away. And even though he retired from the Army as a colonel, he never lost the nickname “LT” either.

And I never forgot his voice—not even over the phone in 2000 after 31 years.

LT told me about an Alpha Company reunion later that year in Dayton, Ohio, and asked if I was interested. A few he’d contacted didn’t want any part of it. But I looked forward to going that year and to the reunions every two years after, meeting up in different parts of the country, seeing the sites, and reminiscing.

It was during these visits that I realized all the guys I’d served with had at least one Air Medal, and some had multiple.

I’d earned a Combat Infantry Badge—a most coveted honor for an infantry soldier—and gotten promoted to buck sergeant while in Vietnam. I’d been issued all the standard ribbons and medals. But I did not have an Air Medal, first authorized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942 to recognize “meritorious achievement” while participating in an aerial flight and awarded to infantry soldiers who participated in 25 air assaults.

We all spent many hours traveling by Huey and Chinook helicopters, participating in well more than the required 25 air assaults. I even traveled in the LOH, now called “Little Bird,” a time or two as part of a two-man sniper team. But my DD214, a report of separation from the service, showed that I had never been awarded the Air Medal.

Jerry Lyons–also known as “Tigerman” top left, with “Chief,” “Groundhog,” and “Ozzie,” in a River Assault Group (Rag) boat in Vietnam. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Not that big a deal in the grand scheme of things, I thought. I had, after all, made it home with all my limbs and most of my brain. I’d moved on with my life. But as time passed, it started to bug me. So I set out to fix it.

First, I applied for my official military records; maybe the Air Medal was there and my copy just hadn’t been updated. That proved a rather arduous task. My request was routed through the system via snail mail to the records office in St. Louis. When I finally got my official DD214, I found, again, no record of the Air Medal.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

There must be some mistake, I thought. So I took what I thought was the next logical step—I filled out a DD214 Correction of Military Records form, explained the situation, and sent it off to the Army Review Boards Agency in Arlington, Virginia.

More time passed.

A response finally arrived. No correction.

OK, I thought. At least I tried. No big deal.

But when I learned later my US senator had a veterans help aide in his office, I felt sure he could help get this done. It was suggested I get affidavits from those with firsthand knowledge of the air assaults.

No problem. Another reunion came up that year, and several Air Medal recipients from the 3rd Platoon agreed to write letters. The oversight seemed to bother them as much as me—maybe more.

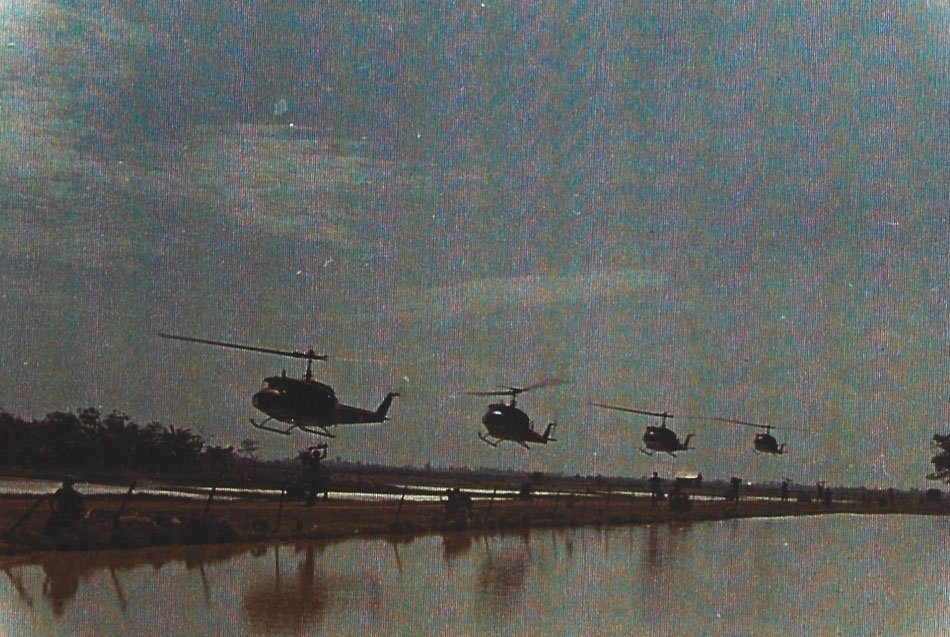

An air assault over rice paddies in Vietnam in October 1969. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Soon after the reunion, the letters arrived—from LT in Washington state, “Doc” Sam Rankin in Montana, “Wimpy” Jim Wiemken in Illinois, and “Moose” Alan Copeland, at the time a prison warden in Pennsylvania.

I expected a quick resolution. It wasn’t quick. It also wasn’t resolved. The senator’s aide advised that without flight records and manifests from the flights, nothing could be done.

I decided that was that.

But it still must have bugged me, because one day I was watching the news and saw a new Louisiana US senator—Oxford-educated, a former state treasurer—making a point about something and thought maybe, just maybe, he could get things done.

I made an appointment and took my thick Air Medal file to his office. This time, I included in my file an explanation of what I thought would have been obvious—that helicopter air assaults by the infantry in Vietnam did not have records of who, what, when, and where. No manifests of passengers existed then or now. These flights had very little detailed planning and were often a short-notice reaction to current events in our area of operations around the dense jungles and open swamps and rice paddies of South Vietnam.

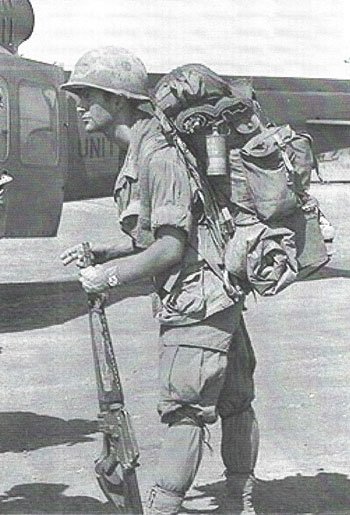

A typical workday in Vietnam. (Photo courtesy of the author)

The incurable optimist that I am, I just knew this was finally going to be the recipe for success.

More time passed. Finally, a letter from the senator’s office. There was nothing they could do.

I’d given it multiple tries, and you can’t fight city hall. I put the file away. That’s the way it goes sometimes, I thought.

Then, a couple of years ago, my niece and her husband—a retired Army colonel who’d commanded an artillery battalion in Afghanistan—visited for dinner.

“I have a bone to pick with that Army of yours,” I said during our visit.

“What’s up?” he asked.

So I told him how, for years, I’d tried to get an earned but never awarded Air Medal entered into my DD214. I speculated that it was probably a simple clerical mistake from the late 1960s. And that, well, we all know how the military bureaucracy works.

Tell us your story: Have you ever battled the bureaucracy to make a change to your military records? Tell us your story by emailing us at pitches@thewarhorse.org to include it in an upcoming newsletter. .

He asked me to copy and send him my file. I did. While I appreciated the thought, I didn’t expect anything to come of it.

Six months later, on a Saturday morning, a package arrived at my house.

What the heck did I order from Amazon or late-night TV this time? I thought as I opened the padded envelope.

Inside was an official-looking leather case. And inside that was an Air Medal.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

What a nice guy, I thought. My niece’s husband went out and bought me an Air Medal.

I called to thank him for the kind gesture.

“Did the corrected records come with it?” he asked.

“No records, but thanks for the Air Medal.”

Then, a few days later, another large envelope arrived containing a corrected DD214 and a full narrative of the proceedings that had resulted in the change by the Army Review Boards Agency in Arlington, Virginia.

I finally realized that this was a real Air Medal—not store-bought. My niece’s husband seemed to know and understand the system, accomplishing in a matter of months what I hadn’t been able to over many years. Now, I looked closely at the back of the medal.

It was engraved with my name.

This War Horse reflection was written by Jerry Lyons, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.