‘Where Were You?’–Memories of Sept. 11 Still Surface Through Veteran’s Portrait

Sitting for a portrait can be fun: tilt your head this way and move your shoulder down. Give a hint of a smile, like the Mona Lisa. That’s perfect. Yet being photographed for the Veterans Portrait Project in the Military Women’s Memorial unnerved me to tears.

I had intended to give a print to each of my children. However, the results were gruesome, and I can’t say where the prints are—just somewhere in the house. I looked for them to help me write this, but they are MIA.

An intriguing online ad introduced Stacy Pearsall, who chose to work through her war-related injuries from deploying to Iraq by photographing other veterans. The idea took off, and within a shutter stop, she had funding for the Veterans Portrait Project to travel around America, shooting candid black-and-whites of any veteran who signed up. A project that had an abundance of volunteers.

Stacy offered a photo shoot the same weekend I traveled to Washington, D.C., with Kelly, a retired Navy chief. Kelly and I met at an Armed Services Arts Partnership veterans’ writing workshop and had become writing and travel buddies. We planned to visit the women’s military museum on the day of Stacy’s event. I encouraged Kelly to sign up too, for she had a distinctive style with red spiky hair and freckles. It would be fun to do it together, like Glamour Shots with grit. Kelly wanted no part of it.

The hardest part was deciding what to wear, a conundrum faced by service members figuring out the uniform of the day. The question of appearance has a different connotation for a military person than a civilian, translating to, “Which uniform is required or appropriate?” A seemingly simple matter, but deckplates humor contended that no two officers or noncommissioned officers ever answered the same way.

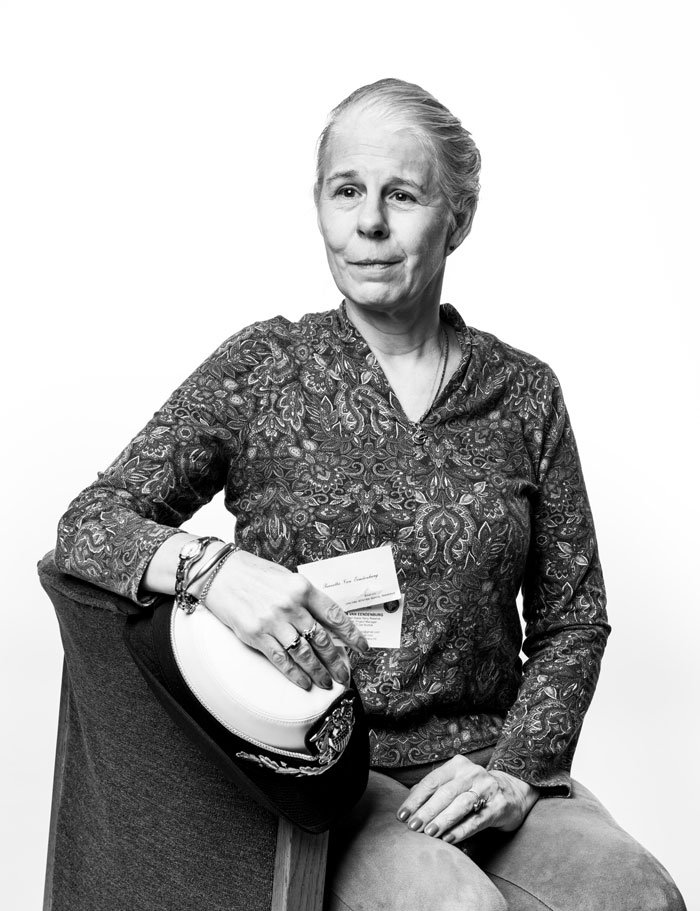

Capt. Reinetta Van brought her Navy officer women’s dress hat—“the same shape as Blue Bunny ice cream cartons”—to a photo shoot for the Veterans Portrait Project. (Photo by Stacy Pearsall/Veterans Portrait Project)

I didn’t want to carry my uniform, so I brought the item from my sea bag that I disliked since first encountering it. The combination cover, the navy brim complementing the bright brass officer’s emblem with a white canvas top, never fit my head. It symbolized my strain of striving to be professional while encumbered by uniforms—read regulations, the culture of ostracism, being set up to fail—that were ill-designed for comfort or performance.

This dress hat, unique for Navy women, would be phased out as the cacophony about matching uniforms between the sexes grew louder. As of Oct. 31, 2016, the oval-shaped hat—the same shape as Blue Bunny ice cream cartons—would be replaced by a unisex version, just like the men wore. It had been different from the start due to the Navy’s effort to offer stylish uniforms to entice women to join.

Kelly let out a howl when I put my hat box in her Jeep. “What the fuck is that?”

“I carry my chapeau in its original hat box. I decorated it with decoupage over 36 years of service.”

She guffawed. “Not so much decoupage as clumsily glued cutouts from magazines: a purple cow, a Cabbage Patch doll, pug puppies. Really?”

I feigned indignity. “Their symbolism should be obvious. And I’ll have you know that ‘Where’s the beef?’ and ‘Don’t bother me I just can’t cope’ saved my sanity often enough to merit inclusion.”

Air Force veteran Stacy Pearsall and her black lab, Charlie, traveled the country for more than 10 years, taking portraits of veterans as part of a project she started in 2008 while rehabilitating from the combat injuries she suffered in Iraq. (Photo courtesy of Veterans Portrait Project)

With that, we drove to Arlington National Cemetery. Knowing it to be huge—639 acres—I had called ahead for disabled parking. I felt relieved when the guard waved us to a small lot only a short distance from the museum. Like many struggling with the shackles of chronic pain, I use energy rationing as a major strategy for completing an agenda. A long walk would have done me in for the day.

This first visit to the Military Women’s Memorial at Arlington Cemetery’s entrance started on a positive note. Kelly and I admired the museum, a curved glass art deco building at the entrance to the national cemetery. After we entered the huge glass doors, Kelly turned left to explore the displays of women serving in uniform. I turned right, carrying my hat box, following the Veterans Portrait Project signs.

Rounding the corner of one wing, I saw the photographer’s setup. What looked like klieg lights surrounded a large white backdrop. An alert black lab lay nearby. I followed the dog’s gaze to Stacy, a slight woman holding a large camera, hair buzzed short and sticking out under a ball cap, a blur of movement.

After introductions, Stacy asked about my service.

Why did you bring this hat? Put it on. I hesitated. I hadn’t anticipated wearing it, only using it as a prop. I would be out of uniform if I wore it with my clothes and non-standard earrings. Oh, what the hell, what can the Navy do to me? I worked for free anyway, as a Reservist drilling for retirement points.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I put on the hat, adjusting it by habit, remembering the repeated instructions the women received at Officer Candidate School about wearing it:

Place your pointer and index fingers on the top of your nose, between your eyebrows. That’s where the brim should be. Reach up to find the gold button on each side. Ensure those eagles are flying true. Pull out the two black ribbons—its tail—to ensure they are free and not caught on hair pins or a collar.

Stacy’s next question elicited another recollection.

Do you feel different with the hat on? The Officer Candidate School training beat it into me: You’re either in or out of uniform. I don’t like being out of uniform. I only wore this bucket hat with my service dress uniform, for formal occasions. Truth be told, putting on my uniform gave me a rush like Clark Kent must have experienced donning his Superman garb. I felt centered, capable, and clear in my identity.

Why did you choose that particular one from your uniform wardrobe? The Navy woman’s bucket hat is iconic. Only officers are authorized to wear it, so it makes a statement. This particular version signifies a senior officer, with gold embroidery on its brim—referred to as “scrambled eggs.” The distinctive oval shape identified it for women.

The light and relaxed conversation between Stacy and me ended with a crash—Where were you on Sept. 11th?

No one had ever asked me that before. I answered curtly, “In uniform at ACT, Allied Command Transformation.”

She circled, snapping shots. “Isn’t that by Naval Base Norfolk? What happened?”

“After the second plane crash, a Marine contingent formed a perimeter defense around the building.”

“Why?”

I rubbed my eyes, wishing I had a Lifesaver peppermint to help divert the upswell of emotions. “ACT is NATO’s North American headquarters. Along with its location by the world’s largest naval base, crashing the building’s huge windows would be a dramatic image.”

Stacy kept buzzing around me, snapping shots. “What did you do?”

“I went home.” I recalled the security officer’s voice over the public address system: Nonessential personnel are ordered to evacuate the building immediately. Shut down your computers. Leave your desk now. Go home until further notice. Her strong voice brooked no room for conversation or deliberation.

Stacy’s questions pushed me into a far-off crypt, overgrown with burrs and frustrations. I couldn’t articulate my anguish that I had no role in stemming or recovering from this national crisis. Support, not service. Always backfill, never the front lines.

I considered pulling my children from school. But to what end? I phoned the schools to ask if it would be a shortened day. However, the schools, like the community, were “business as usual.” Only military bases and stations were evacuating and closing, tightening their perimeter defenses.

Useless. My entire service career had been superfluous. This emergency underscored how expendable I was to the Navy and the country.

Stacy continued shooting and pulling more details out of me. “And then?”

“I started cooking a big chicken dinner.”

Capt. Reinetta Van was shocked by the emotion on the woman’s face in the 20-by-30 black-and-white print that she posed for as part of the Veterans Portrait Project. “Was that really me?” (Photo by Stacy Pearsall/Veterans Portrait Project)

An unnamed dam broke, leaving me unprepared for the painful memories that rolled out in anguished images and sobs. I stood in my kitchen that day and decided to maintain as normal a routine as possible when the family returned. I remember the opening scene around the dinner table that Tuesday as a Norman Rockwell painting. The long mahogany table, covered in food, just fit in the glass-enclosed sunroom. Frank sat at one end, our eldest son at the other. The youngest two sat across from me. My back was to the door so I could pop in and out to the kitchen. And be within arm’s reach of Jimmy, our foster child.

Welcoming another child into our home fulfilled a long-time dream Frank and I shared to raise a big family. Jimmy was the same age as our youngest, although a year behind in the middle school they both attended. His red hair and strawberry-freckled complexion stood out from our brown eyes and hair appearance. His move-in and integration had been more difficult than we had anticipated. Now, three months after he arrived, the lines were drawn: me defending Jimmy while the four overtly rejected the newcomer.

Our differences were underscored pitifully at that dinner table on 9/11. Jimmy chortled, convinced the day’s events were staged, a movie stunt. The stark contrast to our worry and fear as a military family with colleagues worldwide could not have been stronger. Frank and I knew already of two friends on one of the planes that hit the Twin Towers. We braced ourselves for more bad news. We were shocked into silence as Jimmy repeatedly asked to see “the cool TV show” and made airplane and explosion noises.

That marked his death knell in my heart: the realization that regardless of effort or counseling, Jimmy would not join our family. Neither my perseverance nor creativity would change what was a bad match. I could not “make it so.”

Stacy consoled me with a hug. Somehow I regained composure or just ran out of emotion. We had shared an intimate moment, as happens with those who serve, regardless of age difference, combat experience, or career paths.

Stacy signaled the end of the session by putting her camera aside. “Van, you were a good camper. Lots of emotion. Some of the shots are compelling enough to use in my book.”

I joked, “Is that good or bad news for me?” and thanked her for the experience.

Kelly waited for me in the hall. She looked at my mottled face. “How did it go? You okay?”

“Maybe. Not.”

“Not Glamour Shots?”

“Kelly, I don’t know what happened. All this stuff from 9/11 spewed out. …”

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

A clerk handed me a large envelope a few minutes later. I pulled out the photos and gasped. The large format of the black-and-white print, 20-by-30 inches, magnified every line, every pore, and every hair. Not a pretty sight for a 61-year-old. Was that really me?

This shocked me: The emotion that jumped from the woman’s face. Swap the hat for a babushka and she could be a refugee recalling a pogrom that decimated her ancestral village. A mother whose child died. A person facing death.

Four-and-a-half million people have died in war zones since the 9/11 attack on American soil and the USA’s subsequent war on terrorism around the world.

So many reasons for an old woman to cry.

VETERANS PORTRAIT PROJECT To see more portraits and learn more about the project, go to www.veteransportraitproject.com

This War Horse reflection was written by R. Van, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.