New Public Database Will Let Anyone In Swing States See How Their Neighbors Are Voting

When political foot soldiers canvass a neighborhood, they do so armed with voter information, including how many people live in a home, their party, and when they last voted.

Democrats are skilled at canvassing door-to-door because they have so much data about the people in the neighborhoods where they work, some Republican operatives have told The Federalist.

Now a nonprofit, Votermaps.org, is making that information — your information — available online, for free, to any member of the public.

The map is the brainchild of John LeFevre, an author with a banking background; Morgan Warstler, a technology expert who has founded several companies including GovWhiz Inc., according to his LinkedIn page; and Lawrence Abramson, who has a background in entertainment, business, finance. All three are Republicans and support Former President Donald Trump for president, but they say their website is nonpartisan because anyone can use it.

They hope members of the public will become “vote detectives” and look for inconsistencies in voter registration.

“VoterMaps is a searchable, map-based database of all voter histories and current ballot status — updated in real-time. House by house. Block by block. State by state,” the website says. “We level the information playing field transparently, allowing all citizens to be activists, influencers, fraud detectors, and champions of free and fair elections.”

In previous elections, there have been troubling examples of suspected voter fraud, Abramson told The Federalist. For example, a large apartment building where 100 percent of the occupants requested mail-in ballots.

“Nobody can deny that trust and faith in this system has been significantly diminished for a long time,” LeFevre told The Federalist. “If we provide a little transparency to the process … to both encourage people to vote and also to address issues of fraud, or even dissuade fraud, that does, at the very least, help restore some trust and faith and integrity in the process through transparency.”

So far, the website is populated with current data only for Pennsylvania, but it has two states with old data, Ohio and Florida, to show users how it will work.

Fresh data obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State was added to the website this week. The site will then be updated nightly. They plan to cover all the battleground states in this way, as the data becomes available.

Image CreditScreenshot

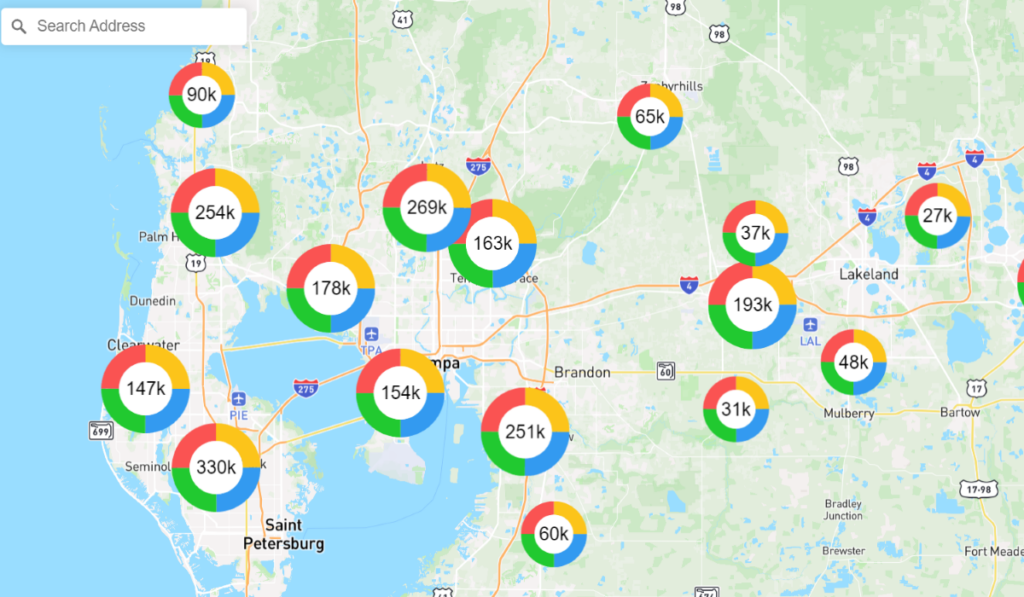

Users can click on an active state where they will find circles with numbers indicating the population of registered voters. Zoom in and the numbers get smaller until the user is close enough to see individual houses on a street map.

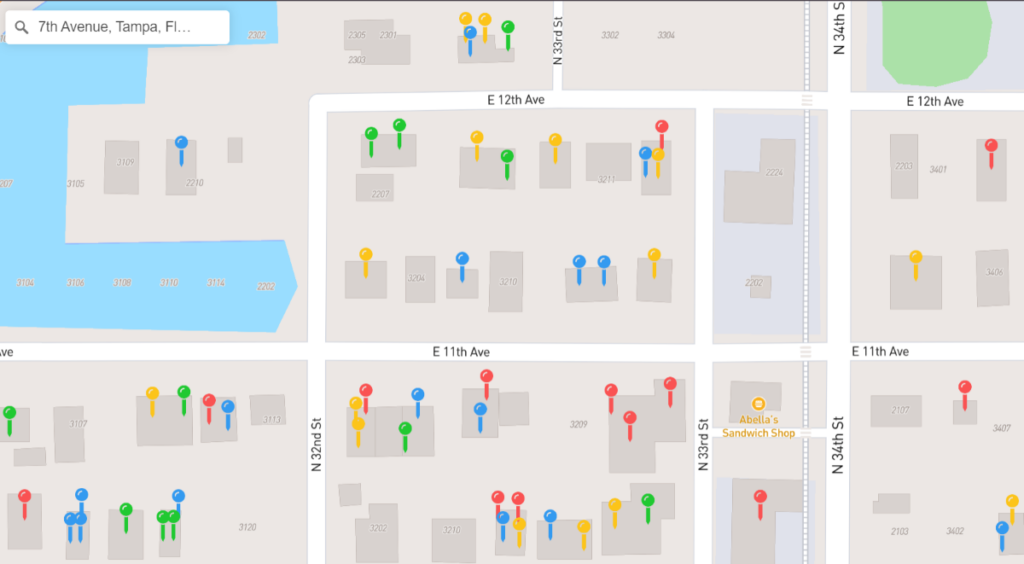

Each address has a number of markers, one for each registered voter in the house. Apartment complexes have loads of markers.

Image CreditScreenshot

The data goes back to 2016 and lists the name and party of each voter. It also shows whether the person voted by mail, and if they voted in the primary or general election. It will indicate if they requested a mail-in ballot for 2024.

Image CreditScreenshot

The co-founders of the site envision citizens looking at the map in their own neighborhood and discovering anomalies. Did the person who died 10 years ago request a mail in ballot recently? Has your neighbor moved away but still appears at your neighboring address? Did the pizzeria down the street where no one lives request 10 mail-in ballots? Did an apartment complex request twice as many mail-in ballots as previous years? LeFevre invites anyone seeing an anomaly to make it public by posting it on X.

“We see too many problems that need to be simplified and I think this is one way to put eyes and ears on this thing.” Abramson said. “Maybe people wake up, and maybe people get a little nervous about doing things they shouldn’t be doing.”

But what about privacy? The data will make it simple to learn someone’s party affiliation, even if they never put a political sign in their yard.

It is public information, LeFevre said, and door knockers already have it. He says there will be a place to click to have your name removed from the map. Although that does not appear on the sample states, it is on the Pennsylvania map. Simply promise to vote and your name is removed. Those who return their mail-in ballot will be removed from the map, he said, keeping the information fresh with only people who have not yet voted.

Although the full voter roll and history is publicly available, it is costly and in a hard to read format. Pennsylvania is charging $6,000 for the data, and Alabama is charging $37,000, LeFevre said.

In many cases it comes in an illegible format that reads like lines of code. It’s cumbersome for any individual to decipher, and every state has a different format. The intention of Votermaps.org is to clean up this data and make it accessible for everyone to use for free.

Beth Brelje is an elections correspondent for The Federalist. She is an award-winning investigative journalist with decades of media experience.

Comments are closed.