Isolated in an Alien World. Separated and United by a Submarine.

The difficulty of separation from loved ones in the military is no secret. It’s well documented to the point of cliché in books, stories, and movies.

It’s reported that troops in WWII would weep upon hearing the song “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.” Just about everyone knows what a Dear John letter is.

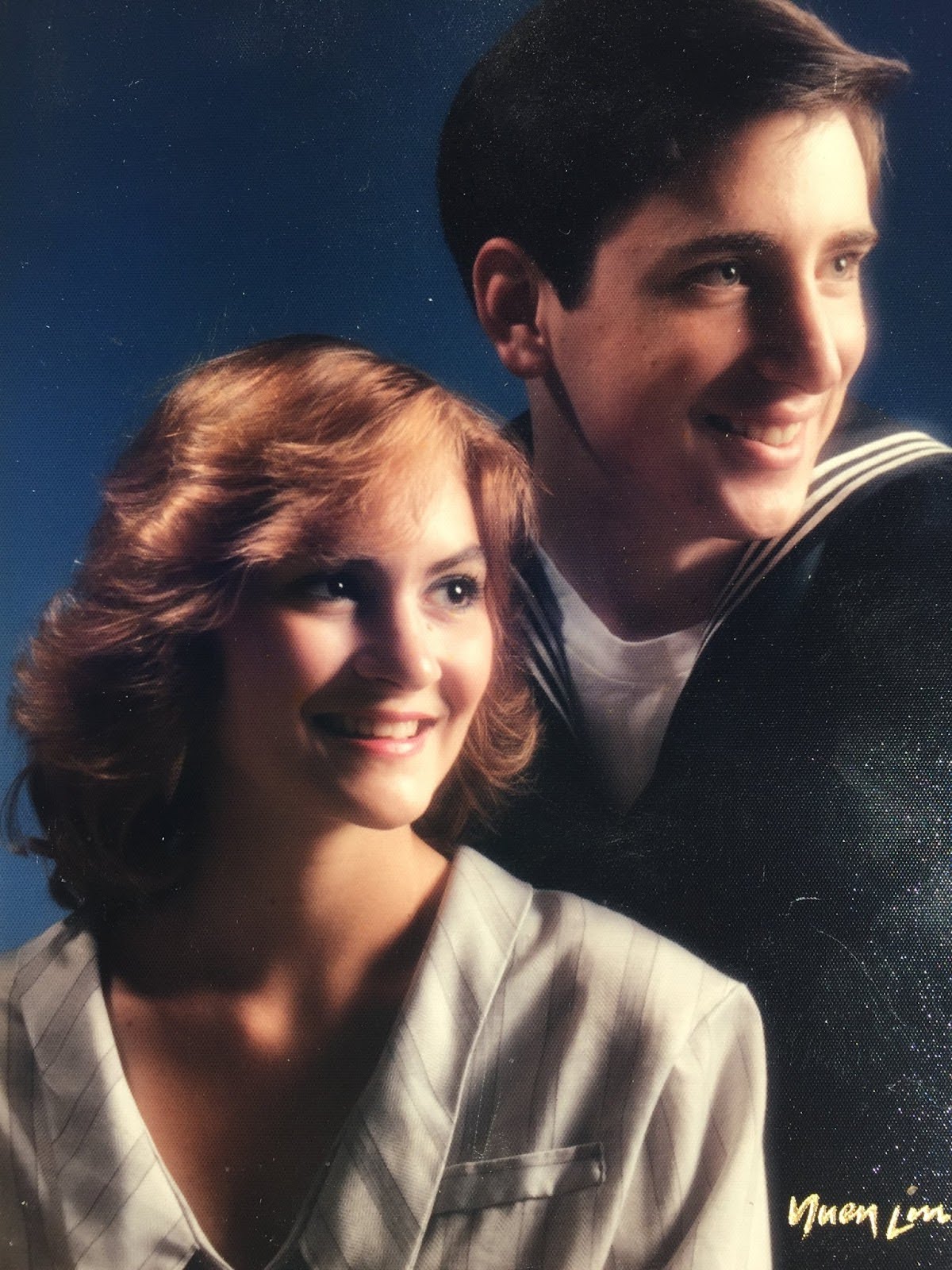

Joelle Bolivar and David Chetlain married in 1985 and would soon endure long separations during his submarine patrols on the USS Nevada. (Photo courtesy of the author)

When I left for Navy recruit training myself, I wondered if I would receive such a letter from my then-girlfriend, Joelle Bolivar. I did not, but several of my peers did—from wives and girlfriends alike. While I shared in their pain, this was just a preview of challenges that lay ahead.

Within a year, Joelle and I married and moved in together. I thought “We made it!” Our relationship survived some long separations—“We can do this!” We had a lot to learn and it’s probably good we didn’t realize everything that awaited us.

While I was still in training, several years of submarine patrols loomed ahead. What nobody tells you about submarine patrols is that they aren’t just separation—they are isolation. Spouses, girlfriends, family, and loved ones have no contact while you are submerged.

No phone calls, letters, or emails, nothing for months at a time.

A submarine could sink on its first day of patrol and it’s possible that nobody would know until they were late to return to port. When the USS Scorpion SSN 589 sunk with all hands, nobody knew when it happened. Family members and loved ones waited hours on a pier in Norfolk, Virginia, for its scheduled return on May 27, 1968, only to be sent home in suspense. The Scorpion was officially reported missing that evening, and family members received the message on the evening news. It took several months of searching before the remains of the Scorpion were found on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, where it rests today with all 99 crewmembers.

Lost at sea, they left behind 99 families whose isolation never ended.

The nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Scorpion rests on the ocean floor 10,000 feet deep, 400 nautical miles southwest of the Azores. (Photo provided by Naval Historical Center)

I completed my sonar training pipeline at Naval Submarine Base Bangor in Washington state, then received orders to report to the PCU Nevada SSBN 733 at the Electric Boat shipyard in New London, Connecticut. Joelle and I were both excited about the cross country adventure and the idea that I wouldn’t be doing any long deployments for a year or more while the submarine was still under construction. At least, that was the hope.

My first day on board, the sonar chief escorted me around the barge and introduced me to the crew. When I met the tactical systems officer, he threw me for a loop with a question: “Petty Officer Chetlain, how would you like to go to sea?”

“I would not like to go to sea, sir,” I immediately responded. “I’m recently married, and my wife and I just moved into an apartment with our dog.”

Clearly the wrong answer.

I was a sonar technician, and “sonar techs belong at sea.”

There was little for me to do in the shipyard, and all of the operating Trident submarines were shorthanded. They augmented their sonar crews with sailors from the shipyard. So within a month, I was sent packing across the country back to NSB Bangor and reported aboard the USS Georgia SSBN 729 along with 5 other Nevada shipmates.

The “refit” period of getting a ballistic missile submarine ready to depart on deterrent patrol is a flurry of activity seven days a week. Between long hours of repairs, store loads, and duty days, I managed to make a few phone calls home to check in. Then we slipped out of port early Sunday morning.

And the isolation began.

While I was in my alien new world, Joelle was left 3,000 miles away in our tiny one-bedroom apartment in the worst part of New London.

This was the point where the submarine community stepped up. The wives club was active and engaged other spouses to make sure they were doing OK. While Joelle has always been very self-sufficient, leaving her in a new and potentially dangerous environment was cause for concern.

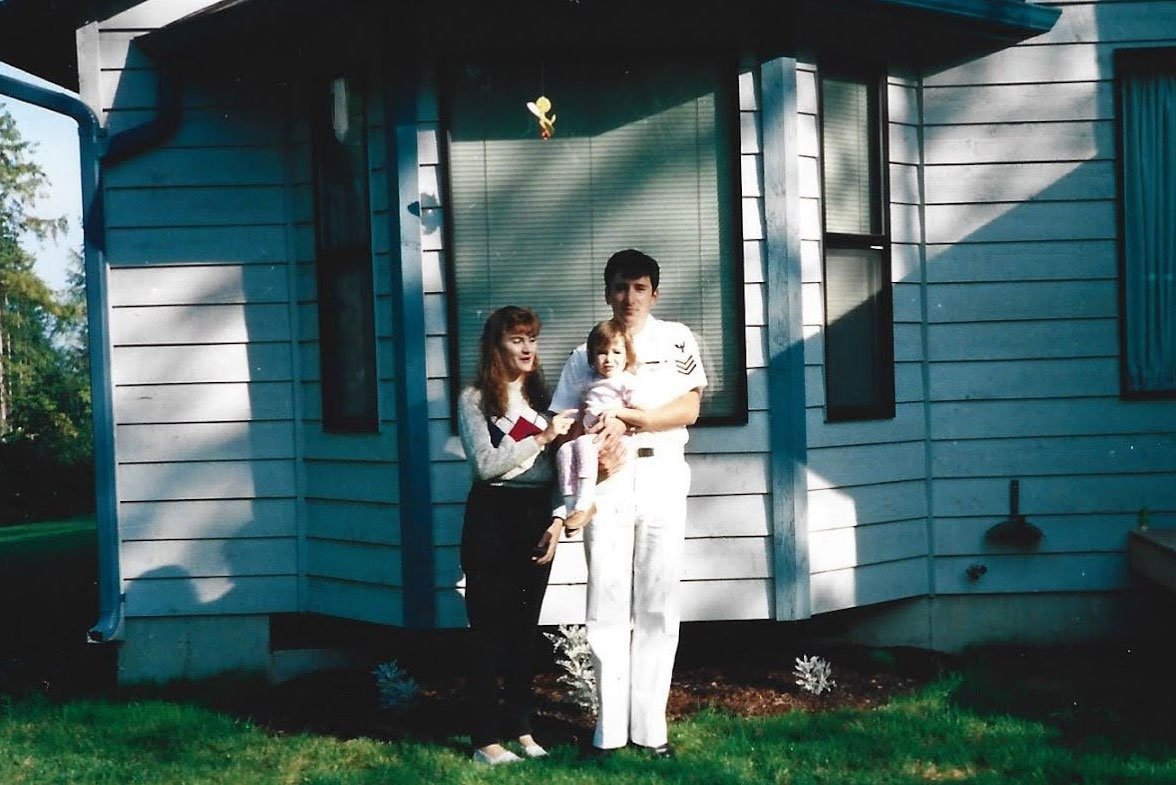

Joelle, David, and daughter, Hayley, lived in this home in Poulsbo, Washington, in 1990 while he was stationed at what was then known as Naval Submarine Base Bangor. (Courtesy of the author)

On my end, the isolation wasn’t 100%. Before leaving, I was issued eight blank “familygrams” that I could send to anyone I wanted.

Of course, I sent them all to Joelle. A familygram was a form that you could enter up to 50 words on and then mail to the submarine squadron or deliver it in a drop box. Once received by the squadron, it was reviewed for content and, if deemed acceptable, would be sent out in encrypted radio transmissions.

There wasn’t much you could say in 50 words, and with censors trying to block bad news from us, one had to be careful what they wrote if they wanted the message to get through at all. We might go weeks without getting any familygrams, but when they were dispatched, it was always an event.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Word quickly passed among the crew that the “familygrams” had arrived, and then the radiomen would print them off and personally deliver them to each crewmember. I treasured every one I received, and I made a habit of taping them on the wall in my bunk.

I can still remember stumbling ashore in Guam 82 days later and finding a pay phone to call back to Connecticut. Thirty-four dollars for a 16-minute call was a lot of money for a young petty officer, but it was money well spent.

I returned to the Nevada just in time for three months of sea trials. After commissioning on Aug. 16, 1986, I went with the Nevada to Florida, and once again Joelle was left behind. So much for our year in Connecticut. By the time we left the state for good in November, we had probably spent about two months out of the past year together.

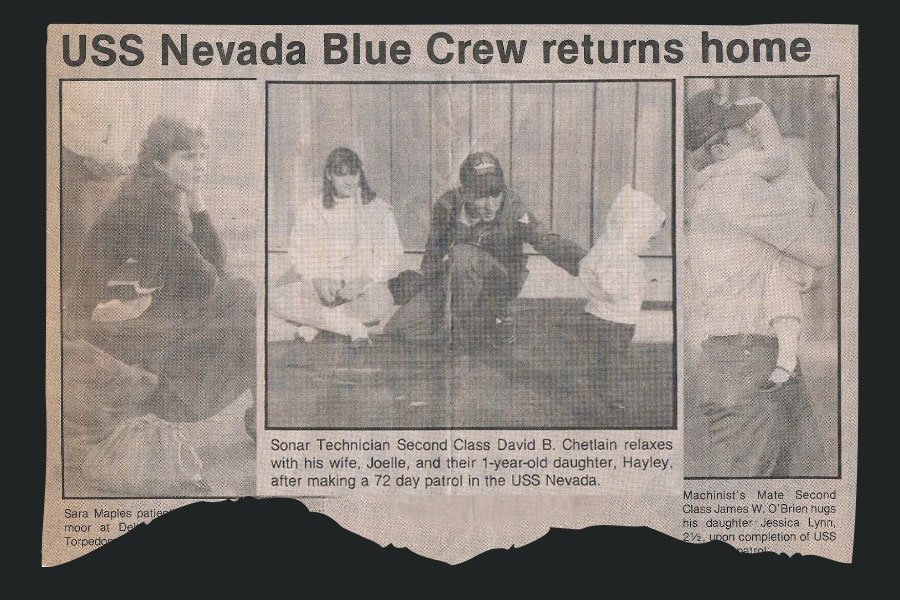

The Chetlains’ scrapbook is filled with memories like this 1988 newspaper clipping, where David, Joelle, and their baby daughter at the time, Hayley, in the center photo, were featured in a photo spread marking the return of the USS Nevada to the Delta Pier at Naval Submarine Base Bangor. David missed Hayley’s first step while he was at sea. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Submarine movements are a closely guarded secret. However, the operating tempo of a ballistic missile submarine has a bit of a rhythm. We would usually go out to sea for 11-12 weeks and then turn the sub over to the “other” crew.

We would help them get ready to go on patrol, and once they left we enjoyed some R and R and spent most of our time in training until they returned. This routine may have created a little more predictability than most people experience in the military. But it also provoked anxiety in family members.

Like clockwork, my mom would call me up when she sensed the submarine was back in port, and we would have this conversation:

Mom: “When are you leaving?”

Me: “Mom, you know I can’t tell you that.”

Mom: “OK, not the exact day—but just give me a window.”

Me: “Mom, no windows. I’m especially not going to tell you anything from my phone in base housing.”

Mom: “OK. … Will you leave before Christmas?”

Me: “I can’t tell you that.”

Mom: “Fine, when will you return?”

Me “I don’t know and I couldn’t tell you if I did know.”

Mom: “OK, then, make a guess.”

Me: “I’m not even going to guess.”

Mom: “OK. … Do you think you will be home by Easter?”

Submariners’ family members often gathered on the Hood Canal Bridge to wave goodbye as the USS Nevada left port for patrols. Chetlain recalls an officer proposing to his girlfriend over a megaphone during the departure. When the sub returned, she was waiting with a sign that said, “Yes.” (Photo by the author)

I couldn’t tell my mom, but I always knew when we were leaving, and so did the wives. That date loomed over every relationship like the sword of Damocles just waiting to drop. The “refit” period when the sub was in port and we were preparing it to deploy again was particularly difficult.

There were no regular working hours, and we could spend days at a time on board. When we would make it home, our clothes stank like amine and we were often too tired to do much more than sleep and turn around and return to work the next day.

Both Joelle and I looked forward to a more regular routine while we despaired about our upcoming isolation. Though, she used to say, “The back-and-forth of refit was worse than the being gone itself.”

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

While we were at sea and unreachable, the wives, girlfriends, mothers, and family relied on each other. In the days before social media or email, the wives club relied on a “phone tree.” And when the crew was finally ready to return home, the news would pass to the wives through the phone tree.

I spent 5 1/2 years assigned to a submarine and completed seven full deterrent patrols along with several “other” deployments. In that span we built a house and Joelle gave birth to our first child. She had a lot on her plate while I was gone.

I was never home for any significant period of time. Relationship problems were often kicked down the road and then picked up again when you reunited.

During that time, Joelle and I would often speculate if we were married because of the sub or despite it. I’m happy to say that after 39 years of marriage, we now know the answer to that question.

This War Horse reflection was written by David Chetlain, edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.