Military Newspapers Told Stories No One Else Did. It Was Our Job to Care.

Newspapers—the old-fashioned, printed, published kind—are meant to be replaced. A day or week of stories and photos, then a new edition. They are like soldiers, giving way to who’s next, like how my responsibilities, across five years and six duty stations, became someone else’s job after I had moved on. Same destiny, no matter how big a day’s headline, or how high a rank.

As the soldier-editor of Fort Belvoir’s Castle newspaper, I used that idea as the June 28, 1991, headline for post commander Brig. Gen. Arvid West’s retirement ceremony—“West Moves On,” above the image of his final salute after 35 years. Commanders are like royalty, a lineage of predecessors and successors. An average soldier needs to trust the Army’s memory that their little effort might be remembered.

The Castle once did its part to be that memory. Each week, headlines, pictures, and stories cataloged Belvoir’s history. Production finished at Comprint Military Publications in Gaithersburg, Maryland, where I pasted down blocks of text and pictures. Comprint took advertising revenue and published the Castle for free, distributing it to racks at the PX or commissary.

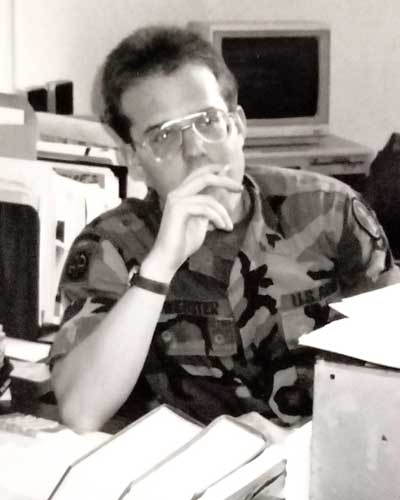

In 1991, Army Sgt. Nathan Webster in the Castle’s office at Fort Belvoir’s Flagler Hall. (Photo courtesy of the author)

Originally named for Belvoir’s then-departed Engineer presence, the Castle modernized its logo that summer of 1991, adding a bald eagle to better connect with the post’s Accotink Bay Wildlife Refuge.

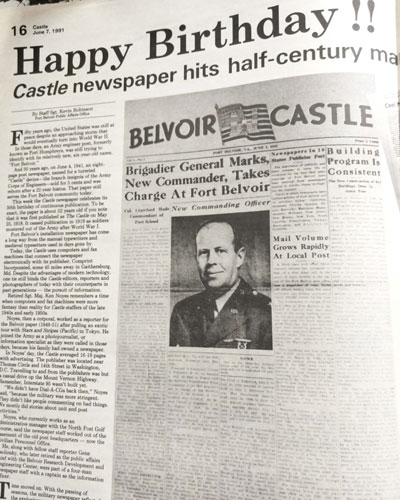

The changes coincided with the 50th anniversary of the Castle’s uninterrupted printed publication. The June 7, 1991, edition used the original Castle logo from June 4, 1941.

Using that old logo was probably my idea. Even if each newspaper was discardable, it made history feel permanent, part of a lineage—that for 50 years, other soldiers had told Belvoir’s story under their era’s Castle logo, same as me.

I had arrived at Belvoir from South Korea in mid-1990, was a Castle journalist, made sergeant, deployed to Desert Storm, and had returned to fill the Castle editor’s role for a couple months before an upcoming reassignment to then-Fort Bragg.

That summer of 1991, I leaned into being in charge. I was a puffed-up popinjay, both insecure and full of himself, high on postwar emotion. I was brusque, I was blunt, and I didn’t care about feelings.

Or I was a young sergeant and had seen other sergeants showing up first and leaving last and who expected everyone’s equal effort. I did what I thought I was supposed to do, and copied what they had shown me.

A new private got too familiar, tried copying the grizzled specialist who I let use my first name. He needed to at least make PFC before earning that privilege.

“I don’t know any ‘Nate.’ My name is Sgt. Webster,” I told him, and I wasn’t joking. I felt obligated to pull rank—isn’t that what rank sometimes requires?

A civilian staff writer enjoyed writing about arts and theater. He reviewed Thelma and Louise and wanted hijrah in the headline—something like “Thelma and Louise: A duo’s epic hijrah.”

It was Arabic for “journey,” and it fit the review, but I said no way that overblown word would appear in a newspaper directed toward average soldiers and their families. If I don’t know a word, nobody knows the word. Get a grasp; this isn’t college.

He wasn’t happy. He changed my mind some of the time. Not that time.

He cared, though. And if I wasn’t nice, I just expected everyone to care. It’s not hard.

Caring was the Castle’s job. The finance clerk, Judge Advocate General’s noncommissioned officer, or civilian data analyst, they just wanted information about why the fire department cordoned off the shoppette—“oh, a propane leak.” Why a bunch of kids were filling the athletic fields—“oh, it’s summer Bible camp.” We quoted their humility when they won Civilian of the Year; maybe they saved the article.

They didn’t care about the rest. It wasn’t their job to care. It was our job.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

The Castle cataloged events small and sometimes dramatic: “Storm Batters Davison,” a headline proclaimed over a front-page picture of a huge hanger roof torn off by a microburst. I sent the private out to do the story. They took him up in a helicopter to get an aerial shot; I assume I was jealous, but it was his turn to do that sort of thing.

No both-sides, no debates, little controversy. If our stories made anyone cynical, that was their fault—we didn’t give anybody anything to be cynical about.

I can read my old stories and say I did OK. I was organized and on point. If my leads were derivative and obvious, that’s the nature of learning how to write.

I’m a better writer now, though it only shows up as an older man’s hobby of now and then.

I have learned how West maybe felt at the end of his career, when one more job, one more rank, could have validated it all.

The June 28, 1991, edition of the Castle commemorates the retirement of Brig. Gen. Arvid West.

West died in 2018. I’m sure by 1991 he understood the leveling. The compromises, disappointments, sacrifices, the running out of steam, and disappearance, after handshakes and a fare-thee-well.

I left the Castle that autumn, left Flagler Hall’s corner office, and my evening runs down to the Potomac, and solo drinking and sundown brooding. I headed south to Fort Bragg, where I never drank alone.

Fort Bragg’s gone—renamed Fort Liberty last year—good riddance to Braxton Bragg. Belvoir could have used a refresh—named for a slaveholding plantation.

But Belvoir’s still here—the Castle’s not, became the Eagle in 1992, foreshadowed by our logo change. Then in 2021, the Eagle flew away, part of the purge of printed base newspapers when the advertising math stopped working. Now, news and events appear on a digital Belvoir Eagle or the Fort Belvoir Facebook page, the command’s information alongside social media’s screeds and nonsense.

In this era of misinformation, that’s not enough separation. The Castle was simple, and simple’s needed, then and now. What happened and why.

In 1991, I believed the printed Castle was irreplaceable—not each week’s edition, but its creation of a lineage. Back then, I read old issues, bound in thick volumes chronicling past decades. I assumed future young soldiers would someday do the same and see their contributions within that shared lineage.

It feels wrong to have surrendered that physical record.

This past summer, I had dug out my small Castle archive for research to argue against the mistake of closing these military newspapers, which told stories no one else did. I would deploy my skills at melodrama and overstatement, and use this War Horse Reflection to make that case.

The more the 30-year-old newsprint stained my fingers, the less that fight stayed in me.

I read the stories from 1991—a school principal’s retirement, an Agent Orange action group, a recycling campaign, the criteria for the Southwest Asia Campaign Ribbon.

These days, stories in the digital Belvoir Eagle still do that job—yearly awards, features on soldiers or civilians doing good work, changes to post policy, visits by retired officers.

Marking its 50th year of publishing, the June 7, 1991, edition of the Castle used the original logo from June 4, 1941.

Printed newspapers didn’t do it differently or better.

On Facebook in April 2024, the Fort Belvoir page posted daily updates about a fuel leak on Davison Airfield, explaining steps to prevent contamination within the wildlife refuge. In 1991, we couldn’t have done that—at best, one story one week, and a follow-up the next.

Websites and Facebook are more convenient, that’s for certain.

Still, convenience is not the same as presence.

Physical newspapers had a presence. A consistent appearance each week, in the barracks and the break rooms. A presence, same as the flag in front of the headquarters. Like the flag, permanence.

In West’s retirement photo, he stands before the Army flag bedecked with campaign streamers—the lineage and honors.

Today’s online era lumps that lineage into a maze of random links. There is no searchable database for the Castle or Eagle. Nor for the Paraglide, Signal, Southern Star, or anywhere I once wrote for the Army. Without a permanent record, history becomes just one more assumption.

Does it matter? Reading about Army life in 1991 is equivalent to myself in 1991, listening to some old-timer drone on about 1958. Maybe it’s silly to care at all.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

It’s silly if campaign streamers are silly—if it’s silly to remember the lineage of Fort Belvoir, and history growing around soldiers who ground through ever-distant days.

In this digital, ephemeral age of 2024, history is a casualty, collateral damage to convenience and efficiency. It’s true that newspapers were made to be discarded each week, but they cataloged history for years into decades. Printed newspapers aren’t coming back, but it should be easier to remember the job they did.

On Fort Belvoir’s 2024 webpage is digital art of almost the same bald eagle I pasted down for its first front-page appearance in June 1991. The eagle is the lineage of replaceable men and women who come and go.

Irreplaceable history. Like I said, it was my job to care.

This War Horse Reflection essay was written by Nathan Webster, edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.