It Took 8 Deployments, 3 Pregnancies, and $43,700 in IVF Treatments for Kristin and Joe to Have Their Baby Infertility struggles impact women in the military at a rate three times the national average, a survey reveals. This is how one Navy couple overcame the obstacles.

The crib and changing table are still in the baby’s room, empty and untouched since Lieutenant Commander Kristin Bowen and her husband, Lieutenant Joe Turnbull, assembled them more than a year ago.

Inside the closet that she painted pink, a collection of yellow and blue dresses remain on hangers organized by wooden placards: 0-3 months, 3-6 months, 6-9 months. Tiny shoes overflow a bin on the shelf above. Striped, floral, and polka-dotted headbands with bows dangle over hooks on the wall.

Kristin and Joe, both Navy pilots, are expecting a baby in three months. It’s their third try in more than four years—the dates blurring into a jumble of anticipation, elation, and crushing disappointment. For young military couples like the Turnbulls, serving their country can mean sacrificing their chances of starting a family, especially when fertility issues arise.

On this rainy April afternoon in the couple’s coastal Virginia home, Kristin, 37, beelines for the closet, passing the dresser that Joe, 35, carried down from their attic with the help of a cousin. In bare feet and maternity yoga pants, she approaches the center of a rose-colored rug and steps over the spot where in May 2023—on what would have been her due date of pregnancy number two—she collapsed to the floor and wept beside an empty bassinet.

Almost a year later, with hope restored, she plucks a yellow onesie and a Ranger-green headband from the closet and hurries downstairs. “Do you want to see my favorite outfit?” asks Kristin, a curvy five-foot-nine with a baby bump. She displays a yellow one-piece that reads “Mommy’s CO-PILOT” in camouflage lettering with a helicopter depicted underneath.

Baby clothes still hang in the pink-painted closet, separated by ages, waiting for the baby girl who will wear them. Kristin’s favorite is a onesie with a helicopter for “Mommy’s Co-Pilot.” (Photos by Erin Edwards)

By now, Kristin had expected the outfit to be covered in spit-up, faded from repeated washing, and too small for the daughter she and her husband had tried so desperately to bring into the world.

From the moment Joe got down on one knee and fished a ring out of his sock on a beach in 2019, they started trying to get pregnant.

Kristin cared more about a baby than a wedding. Having seen Navy friends struggle to conceive, she was aware that her journey to motherhood could carry more hardship than those of her civilian friends.

She didn’t know at the time that servicewomen, who make up about 17% of active-duty forces, have a higher infertility rate than the general U.S. population, according to a Women’s Reproductive Health Survey. A 2018 survey revealed that 37% of servicewomen and veterans said they struggled with infertility, a rate that is three times the national average.

Kristin knew her fertility could be negatively affected by her age. But she didn’t consider what the stress of her job, unpredictable and long separations from her husband, disruptions in medical care due to deployments, potential radiation exposure from ships, and limited insurance coverage would mean for her chances of starting a family.

No Benefits for IVF Treatments

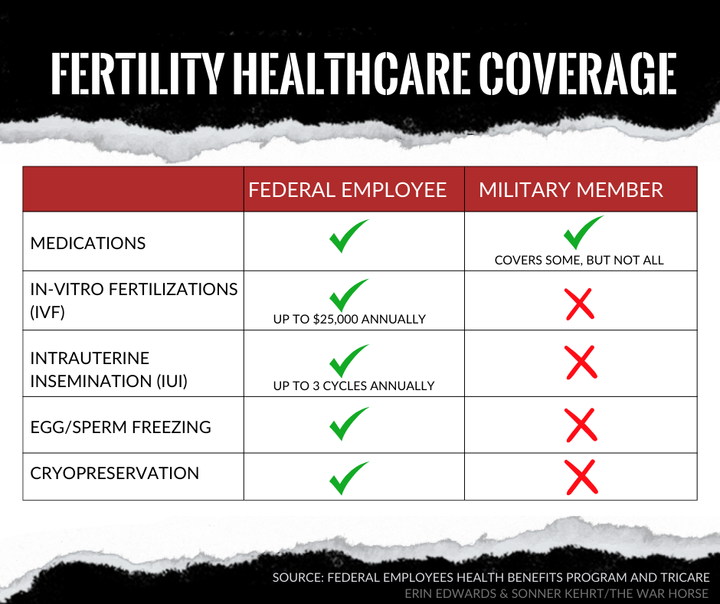

Military service members do not receive funding for assisted reproductive services unless their fertility issues are a direct result of an injury on active duty. That’s in sharp contrast with benefits that civilian federal employees receive: In 2023, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program started covering fertility services from in vitro fertilization to egg freezing for federal employees with additional coverage to come in 2025.

Democrats in Congress introduced a bill this year to extend coverage for fertility care to active-duty servicewomen, but Republicans have twice shot down the Right to IVF Act, which would make access to in vitro fertilization and other treatments a right to women nationwide.

“I’m happy that some people can get care,” Kristin said, “but I’m jealous that it’s not the same for us.”

In April, 14 weeks until their due date, the couple’s meticulous, four-bedroom home in Norfolk, Virginia, is filled with symbols of sorrow and hope—the emotions locked in the compartments of Kristin’s mind.

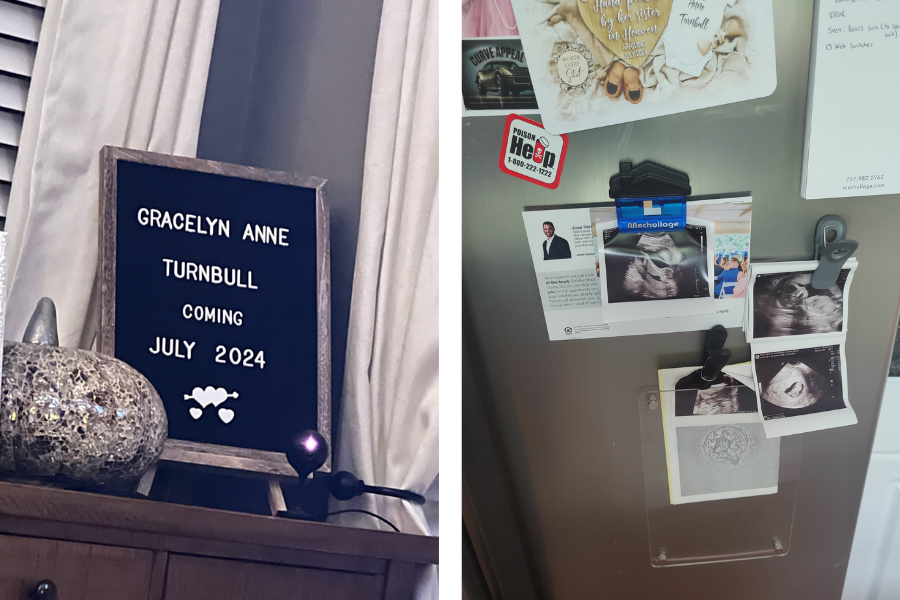

In the living room sits a felt letterboard announcing “Gracelyn Anne coming July 2024.” The stainless steel refrigerator displays images of sonograms between an organized calendar and to-do list. Across the granite countertop is a large sink underneath a bay window overlooking the backyard pool. Kristin washes a glass near a collage of framed photos: One is of her in a blue hospital gown holding a palm-sized baby wrapped in a pink-and-purple knit blanket and cap. In the dining room, on the middle shelf of an armoire, is an unassuming white porcelain jar, bearing a name and date—Charlotte, Feb. 19, 2023—the urn of their stillborn. Underneath her name are imprinted tiny footprints.

The same footprints are now tattooed onto Kristin’s forearm and Joe’s back.

There are signs throughout the couple’s home in Norfolk, Virginia, that Kristin is pregnant again. One in the living room is like a movie marquee announcing the coming attraction while images of sonograms cover the refrigerator in the kitchen. (Photo courtesy of the Turnbull family)

‘I Watched the Clock Tick Away’

In October 2016, a mutual friend introduced Kristin and Joe at a busy bar in Yokohama, Japan, during a port call. A friendship over their New Jersey roots eventually blossomed into a romance. She noticed his Jersey boy tan and bicep tattoos. He fell for her womanly curves and strong convictions.

By November 2019, they were engaged and began trying to get pregnant, despite only seeing each other on weekends with Kristin being stationed in Virginia and Joe in Florida. After almost a year had passed with no success, Kristin and Joe wanted fertility testing, one of the only reproductive benefits covered by TRICARE, their military health insurance. But TRICARE would not schedule testing until the couple tried getting pregnant for an entire year regardless of deployment cycles, Kristin recalled.

In the Navy, deployments or detachments are typically defined as time away from a servicemembers’ home base. They can last from several weeks up to six months at sea. So in January 2020, Kristin adhered to her official deployment orders, packed her sea bags, boarded an aircraft carrier, and served as a flight-deck “shooter” where she worked long hours, checking winds and crouching low to launch jets in the Middle Eastern heat. For four months, she shared a computer with 12 officers to communicate through email with her then-fiance who was in a time zone eight hours behind.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

“I watched the clock tick away without any hope of starting a family,” Kristin said.

The deployment ended by the beginning of May, and she returned to her duty station in Norfolk. But Joe was stationed in Milton, Florida, so they were still 900 miles apart. They planned visits based on Kristin’s ovulation schedule. During the severe lockdown stage of Covid-19, this meant driving 15 hours in a day to continue to try for a baby.

After two and a half years of trying, Kristin, then 34, got pregnant six weeks before their wedding. Everything was coming together—the wedding, the man of her dreams, and a baby to follow. Then, just before the July 4th weekend in 2021, two days before “what was supposed to be the happiest day of my life,” she miscarried. Compartmentalizing as she is trained to do, she put on her white wedding gown, posed for photos with a big smile, and danced as they had rehearsed.

Kristin and Joe put on a good face for their wedding in 2021, just days after a miscarriage ended Kristin’s first pregnancy. (Photo by Deborah Ryan)

Navy family planning schedule

She and Joe were determined to start getting fertility testing. However, Kristin said, their military doctor told them that they needed to be “unpregnant” for at least a year to confirm they had a fertility issue.

Kristin did her best to adhere to an unwritten Navy family planning schedule, but, like many women, her reality looked different than the Navy’s recommendation. The expectation is to find a partner, get pregnant, and deliver within what is known as a “shore tour.”

Shore tours are typically three-year periods where the service member is in a nondeployable job, meaning they go home at night and have a more predictable schedule. For a naval aviator, this type of tour occurs about ages 28 to 31 and 36 to 39.

“Family planning is usually during shore tours. That first shore tour is traditionally the optimum time to aim for pregnancy,” said Capt. Chandra Newman, prospective commanding officer of Naval Air Station Pensacola.

But romantic pursuits, biological clocks, and deployments don’t sync up that easily. Kristin was 29 when she met Joe, who was 27. By the time she and Joe got engaged and started trying to get pregnant, she was 32, the age when females’ eggs decrease more rapidly until 37 when there is a significant decline, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Kristin and Joe were often separated, like in December 2021 when she attended mountain flying school in Nevada above. Long deployments and stressful jobs as Navy pilots added to the Turnbulls’ challenge of starting a family. (Photo courtesy of the Turnbull family)

Fertility treatments such as egg or sperm freezing, artificial insemination, IVF, and egg storage would help women service members meet the demands of the job, advocates say, and allow male service members to better plan a family around their deployment schedules.

In January 2022, at age 35, Kristin packed her sea bags again, boarded another ship and sailed 6,000 miles from Norfolk, typing emails to Joe for six months. After she returned home, Joe finally moved in with his wife—six years into their relationship. They were ready to pursue assisted reproductive technology services.

Instead, they got a surprise. They were pregnant again.

Kristin’s friend Meghan planned a baby shower in Norfolk while her mom sent out invitations for one in New Jersey. Gifts flooded their four-bedroom home with the backyard swimming pool. At 22 weeks, mauve drapes and lavender curtains completed the nursery.

But at 27 weeks, there was more devastating news. She couldn’t detect a heartbeat.

‘Saying It Out Loud’

Kristin was having trouble breathing. A self-sufficient, headstrong woman, who thought, “I think I’m being dramatic,” she told Joe to stay in bed while she drove herself to Chesapeake Regional Hospital where her blood pressure registered 190 over 110 and rose to more than 200, indicating severe preeclampsia, a life-threatening hypertensive disorder.

The nurses performed an ultrasound without delay. When the heart monitor appeared on the screen, there was nothing.

“I didn’t believe it until the doctor came in and said it. I called Joey. Having to say it out loud …” Kristin’s voice trembled, then she continued through tears, “that made it real.”

After three rotations of nurses and more than 10 hours of labor, Kristin gave birth to their stillborn, Charlotte. She and Joe wept as they held their child for the first time. Then a chaplain baptized Charlotte in holy water from the Vatican that Kristin brought back from deployment before the couple held her for the last time.

Photos of Joe and Kristin holding their stillborn baby girl are accompanied by Charlotte’s tiny footprints. (Photo by Erin Edwards)

Joe imagined carrying their baby home. Instead, he clutched three funeral pamphlets. He sat alone at the computer reading reviews of funeral homes. Joe was determined to have his daughter cremated. “I saw it as us leaving her, if we buried her,” he recalled, struggling to complete the sentence. “Kristin doesn’t even know this, but I walk by [her urn] and I either kiss my hand and touch it or I blow her a kiss before I go to work.”

After six weeks of living in a fog, imagining what they would have been doing had Charlotte lived, Joe returned back to flying MH-53E Sea Dragon helicopters out of Naval Station Norfolk. Kristin followed to her military desk at Naval Support Activity Hampton Roads soon after.

But they weren’t giving up.

Sparing no expense

In June of 2023, they began IVF treatments, hormones, an egg retrieval, embryo transfer, more doctor’s appointments, and racked up $43,700 in medical expenses.

“It’s robbery,” Joe said. “They’re not selling a product. They’re selling a life, a lifestyle, and a future.”

Those are the expenses that Sen. Tammy Duckworth, an Illinois Democrat and military veteran who used IVF to have her two children, fought to eliminate when she championed the Right to IVF Act in June of 2024. The bill—twice blocked this year by Senate Republicans, despite former President Trump’s recent pledge of support for IVF—would have required insurers to cover fertility treatments for military members and veterans.

“Our servicemembers expect to sacrifice for our country—but they should never have to sacrifice the ability to start a family,” Duckworth told The War Horse in a statement, vowing to keep fighting for IVF access. “Learning about Kristin and Joe’s struggles is heartbreaking.”

For Kristin, no amount of money would surpass her emotional and physical investment to have a child. So she and Joe embarked on a five-month IVF journey.

“For 100 plus days, I stuck massive needles into my wife,” Joe said.

Inside the needles are hormone medications that stimulate the ovaries to produce eggs. Each injection carried hope—and, eventually, positive results.

Six eggs were retrieved. Then five were fertilized. And four turned into embryos.

On Nov. 16, 2023, a female embryo was successfully transferred. Kristin and Joe cried tears of joy for the first time in over two and a half years.

“I felt super hopeless through most of it…I felt like it would never happen,” Kristin said. “When it did, I was very excited but also scared something terrible would happen.”

During her third pregnancy, Kristin often visited her midwife for sonograms and checkups. Given her history, she was constantly on high alert. (Photo by Erin Edwards)

‘Let’s See Your baby’

Two months after Kristin was pregnant for the third time, Joe deployed to the Middle East.

In mid-April of this year, two-thirds into her pregnancy, she met with her midwife in a room at the Naval Medical Hospital in Portsmouth, Virginia. Josh Gilliam, 48, has sandy blond hair, rosy cheeks, and attentive eyes. He understands that high-risk patients with a history like Kristin’s will be more comfortable with more ultrasounds and monitoring, which she likes.

“Twenty-four weeks. We’re getting close to that same time again. You’re probably feeling a lot of things. Keep an eye out for signs of preeclampsia,” Gilliam advised her.

“My cough still won’t go away,” Kristin asked. “Will it hurt the baby?”

“No, but I don’t want you going your whole pregnancy with that,” Gilliam said before prescribing Kristin medication.

“That medicine won’t hurt the baby though, right?” Kristin asked.

Gilliam reassured her. Then he said, “Time for the fun part. Let’s see your baby.”

Kristin undid the waistband of her two-piece flight suit, which a neighbor helped expand into a maternity suit since her Navy-issued maternity flight suits never arrived in time for her previous pregnancy. She lifted her shirt to expose her belly. Gilliam measured her stomach, 23.5 inches. Then he placed white paper at the crook of her pants. He made small talk as he applied gel and prepped the ultrasound machine.

He flipped off the lights and as their attention shifted to the screen, he never stopped talking.

“Baby’s head is over here. Left thigh, knee, calf, left foot. Girl bits right there.”

Then the heart monitor appeared on the screen.

Silence. A second or two passed. No one dared to speak. A heartbeat pulsed across the screen, then another, and another.

Only the beating heart filled the air. Kristin stared at the monitor, lost in the rhythm.

“She sounds really happy,” Gilliam said, breaking the silence.

“How quickly would she stop breathing if the umbilical cord wraps around her neck?” Kristin asked.

Her midwife is prepared for questions like this. He retired after 30 years on active duty and continued to work at the military hospital serving only high-risk patients. Gilliam reassured her that a cord wrapping around a baby can be a common occurrence but almost always undoes itself.

Kristin frowned and tilted her head, unsatisfied with his answer. She is used to knowing protocols, following checklists, and rehearsing emergency procedures. If there’s an engine failure, or umbilical cord choking her baby, she wants to know the exact steps required to fight the emergency in time. She wants to rehearse it, memorize it, analyze it, and practice it to near perfection.

He shifted her attention back to the screen. “She almost looks like she’s smiling,” he said.

Kristin looked at her baby and smiled back.

Gracelyn Anne Greets the World

Joe expected he would receive a Facebook message from Kristin the moment she began to go into labor, catch an emergency leave flight from Bahrain and pray to arrive in time for the birth. To his surprise, his command made sure he wouldn’t miss it, sending him on a flight in early July.

After three layovers and 18 hours of travel, he arrived home on July 7. Kristin’s anxiety increased with each passing day, reliving the trauma of her previous pregnancies.

“Any time I didn’t feel her, I went in [to the hospital],” Kristin said, “I had been to labor and delivery several times.”

On the morning of July 12, she panicked again, unable to feel fetal movement, and drove to the hospital to discover everything was normal. When they offered to deliver her a day early, she jumped at the opportunity.

Joe arrived at the hospital carrying a pink blanket and onesie they made special for their newborn. Gilliam and his delivery team performed a cesarean section and a healthy six-pound, 13-ounce baby named Gracelyn Anne greeted the world.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

“Overall it was an extremely stressful and emotionally exhausting roller coaster that luckily ended in everything we wanted,” Kristin said.

Gracie, who has Kristin’s nose and Joe’s smirk, was introduced to her new home a couple days later. She was an easy newborn, never waking more than twice in a night. As a dual military couple, they’ve been prepared for parenthood.

“It’s been noted that being on deployment is basically like living in a series of naps, so that’s pretty much what having a newborn is like,” Kristin said.

Joe started flying again after a month and a half and was sent to provide relief for Hurricane Helene in North Carolina for five days. Kristin’s command is allowing her to work from home for a week at a time. They will alternate each week, taking turns being home with Gracie, who is becoming less predictable in her moods and sleep schedule.

Now, the Navy pilot parents are determined to give Gracie a sibling.

They have a calculated plan in place for their next embryo transfer—June 2025, just before Joe leaves on a future deployment, allowing him to return in time for the birth, and meeting the doctor’s recommendation of having a second child after 18 months.

In their Virginia home, now alive with rattles, bottles, and spit-up rags, Joe tightly wraps a crying Gracie into a blanket and jokes, “Swaddling will continue until morale improves.”

When asked what IVF gave to them, their answer is simple: “Everything.”

Gracie rests with mom and dad near the tattoo on her father’s back of angel wings, a rose and Charlotte Evelyn’s footprints. They will always be sisters, but Joe and Kristin hope to add another sibling to the family in the next year. (Photo by Diane Sebasiano)

This War Horse feature story was reported by Erin Edwards, edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines. Coverage of veterans’ health is made possible in part by a grant from the A-Mark Foundation.

Comments are closed.