My Platoon’s Fight To Survive—and Heal From—The Bloodiest Battle in Iraq A Marine Platoon’s House-To-House Fight Through The Bloodiest Battle in Iraq

November 10, 2004

Crossing Fran

Javelin missiles shriek through the sky. Machine gunners fire from the rooftops. Artillery thumps in the distance moments before a thunderstorm of steel rain pours around us.

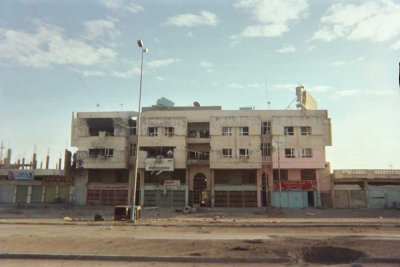

Phase Line Fran was a multilane highway Marines sprinted across on Nov. 10, 2004. (Photo by Thomas Brennan)

Our squad is crammed into a room at the south side of the government complex, waiting to sprint across Route Fran, the multilane highway that separates us from our three-mile, house-to-house battle through the city.

Looking back, Route Fran was a final buffer from the real carnage and a life-altering demarcation point for all of us.

Once we crossed over, life would be different.

The change would be forever.

“One minute,” someone yells.

My heart is racing.

I’m scared.

The time passes in an instant.

Yut. Err. Kill.

Lance Cpl. Michael Briscoe and Lance Cpl. Phil Barker prepare to clear a house in Fallujah. (Photo by Cpl. Trevor Gift)

Sgt. Leo takes off across the road, and we sprint behind him.

I hop over the center median and rush toward the sidewalk. Electrical wires dangle from street poles. Rubble is scattered about. A thick black smoke dances in the air.

We peer through shattered windows and broken doors as we pass by shops and offices damaged by the airstrikes and rockets.

As we rush down the first alley, second-story windows erupt with gunfire. We’re pinned down.

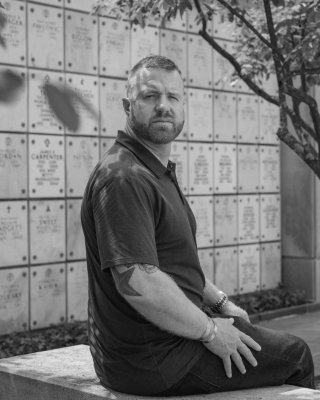

Cpl. Robert “Day Ball” Day — Machine Gunner, Alpha Co. near the National Museum of the Marine Corps. (Photo by Matt Eich for Mother Jones)

Some Marines break off to clear nearby houses. Cpl. Robert Day, a 24-year-old from Mobile, Alabama, sprints to the roof with his machine gun and a team of snipers in tow. Bullets whiz and ricochet around him, peppering him with chunks of brick and mortar. Day presses his shoulder into his machine gun as a fighter with a backpack full of rockets sprints down a street.

Search. Traverse. Fire. Repeat.

Simultaneously, the rest of our platoon maneuvers down the street, returning fire and bounding from position to position.

“Get those rockets up here!” Sgt. Leo screams, from the front of our patrol. He’s standing beside a compound wall and is unfazed by the firestorm surrounding us.

He’s calm amid the chaos.

I prop my launcher on my thigh as my team leader, Michael Briscoe, inserts a high-explosive rocket. Together, we sprint to the middle of the street. I prop the weapon on my shoulder and press my face against the launch tube to look through the scope.

Michael Briscoe rests beside Thomas Brennan during Operation Phantom Fury. (Photo by Cpl. Trevor Gift)

Bullets are hitting all around us as Briscoe turns around to make sure no Marines are standing behind us.

Dozens of them are. But there’s no time for protocol.

He slaps my shoulder and screams in my ear, “Backblast area all secure! Rocket!”

Ten pounds disappear from my shoulder in an instant, and the second story of the house is destroyed.

The gunfire stops. For a moment.

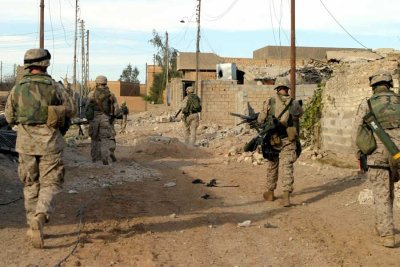

A squad of Marines patrols the streets of Fallujah in November 2004. (Photo by Cpl. Trevor Gift)

The enemy takes pot shots over and around walls as we move from one home to another. We find a network of blown-out walls, allowing fighters to maneuver from house to house. Mattresses are boobytrapped with grenades and cutouts for people to hide inside. We find tripwires and machine gun bunkers reinforced with sandbags.

Sgt. Leo often takes point alongside Lance Cpl. Bradley Faircloth, clearing almost every home we go into. He lobs grenade after grenade over compound walls and has me blow open door after door with explosive charges. Across the street, Gary Koehler gets shot in his leg, and Matthew “Doo Doo” Brown is shot in the buttocks like Forrest Gump. Then Brian Passolt takes a machine gun burst to the stomach.

Back home, the three of them aren’t yet old enough to buy a six-pack of beer.

They’re stacked into the back of a vehicle like a cord of wood and disappear into the distance.

By nightfall, we’re still clearing our first street inside the city and occupying a house for the night. Some sleep in beds, others on pillows and piles of clothes. I am relegated to the rooftop with the boots and sleep beneath a blanket of stars between hour-long shifts of guard duty.

The next morning, we wake up before sunrise and continue our weeks-long journey south.

Eat. Sleep. Shoot. Shit. Repeat.

Marines man fighting positions on a rooftop in Fallujah. (Photo by Cpl. Trevor Gift)

For days, the firefights are constant as we clear house after house. Machine gunners fire from the hip as we rush down streets. I fire dozens of rockets and we use so many grenades that we run out. I begin to prime sticks of C4 for us to throw instead. The blasts break prayer beads and tear Qurans.

In the moment, destroying heirlooms and wedding photos during searches and defecating in bathtubs to avoid being exposed to enemy fire outside feel necessary. But they’re some of the things that bother me most 20 years later.

At one point, an officer specializing in chemical weapons identification tells us that we’ve discovered drums of chemical weapons known as “blood agents” and that we should vacate the premises. We do as we’re told. We also discover a torture chamber. Decades later, I still have nightmares where I’m trapped in that small metal cage.

Munitions explode in the distance as the Marines of 3rd Platoon fight from a high-rise building. (Photo by Cpl. Trevor Gift)

One morning, our patrol stops at the edge of an open field. We’re ordered to run across, and one by one, we sprint hundreds of meters toward a cluster of three-story homes.

One hundred pounds of rockets and explosives press into my flak jacket as I rush across the uneven ground, dodging ankle rollers, barbed wire, and mounds of dirt.

Puffs of dirt jump from the ground as bullets snap and whiz around us as our boots suck into the wet earth.

The charging handle of my rocket launcher digs into my thigh with every step.

My gasps for air drown out the noises around me.

Somehow, we all make it.

We climb the stairs of the building, and the squad mans defensive positions on every floor. The Marines on the roof take cover behind a short wall and begin to return fire as enemy fighters take pot shots from nearby windows and scurry through alleyways.

Our lieutenant quickly realizes we’re at a tactical disadvantage. We’ve been holding our position for too long, and the enemy has surrounded us on three sides.

Cpl. Mike Ergo dragged his wounded sergeants from a rooftop after a rocket attack. (Photo by Matt Eich for Mother Jones)

Shell casings pile up at our fighting positions as enemy tracer rounds penetrate the wall and dance across the rooftop until they fizzle out. Talking machine guns play a game of insurgent whack-a-mole. I watch fixed-wing aircraft drop bombs in the distance.

Mike Ergo, a 21-year-old from Walnut Creek, California, who joined the Corps to play the saxophone, is on the roof smoking a cigarette and scanning for enemy fighters when he hears a whoosh as a volley of rockets slams into the front of our building. The blast briefly knocks him unconscious.

As Ergo pulls himself off the ground, he sees the wall beside him is destroyed. He hears gunfire and tastes explosive residue.

“I’m hit,” Sgt. Leo screams from nearby, as the wall explodes around him. He clutches his leg. A deep purple bruise quickly spreads across his hip and thigh. Then Sgt. Nathan Fox, a 21-year-old from Berryville, Virginia, takes shrapnel in the shoulder. Ergo and another Marine rush to drag them from the roof.

I watch as our wounded are carried downstairs. Leo objects the entire time. He’ll walk it off, he jokes. Our lieutenant worries Leo’s femur is broken and forces him to leave, assuring him he’ll return soon.

For the first time, we see fear in Leo’s eyes.

As the firefight continues, our wounded are driven to the hospital. Morale crumbles. There’s an obvious void as we continue to push through the city.

Sgt. Leo was more of a security blanket than we’d realized.

Comments are closed.