Q&A: Twenty Years after Fallujah – ‘I Hope They See It As a Cautionary Tale’ The War Horse executive director and founder Thomas Brennan on the emotional journey behind his reporting on Operation Phantom Fury.

The War Horse’s coverage this month of the 20th anniversary of the Second Battle of Fallujah is deeply personal.

Our founder, Thomas Brennan, deployed to Iraq two decades ago as a young Marine barely out of boot camp. Within months, his platoon—along with thousands of other American, British, and Iraqi troops—was sent to Fallujah with orders to wrest the city from insurgent control. The battle would later be described as the toughest combat Americans had faced since the Vietnam War.

Twenty years later, Brennan brought his squad together again to document what they had experienced in Fallujah and to honor Lance Cpl. Bradley Faircloth, who didn’t make it back home.

In this conversation Brennan explains the emotional journey behind this project. It’s been edited for length and clarity.

TWH: This project is the result of months of long, hard work. How are you feeling?

Brennan: I’m feeling a mix of emotions. I recognize that I’m closer to the story than I usually am on the things that I report. One thing that’s similar is that in this instance, I cared about my sources, who happened to be the Marines I served with, respecting the story that I told, that trust was well-earned, and that I delivered on a solid piece of journalism, which is what I promised them.

There have been moments where it has definitely had negative mental health consequences for me, where I’ve been depressed or extremely anxious or just trapped in a moment inside my mind. But now that things are starting to roll out, I feel better. I feel lighter. Knowing that the company and that the Marines that I served alongside feel heard and seen and that it’s helping them is helping me at the same time.

TWH: Take me back in time. How did you come up with the idea for this project?

Brennan: Right around the 19th anniversary [of the battle], when the Israel-Gaza war was in its infancy, on the news they were mentioning that Fallujah veterans were being sent in to advise the Israelis. And it really struck a chord with me that everybody was just, “Send this in, send that in, do this, bomb that.” Not once in the conversation did I hear people mention what it was going to do to people like me, or people like Doc [Reinaldo Aponte, the Navy corpsman who tried to save Lance Cpl. Faircloth], or the other people that I served with.

Sometimes military force is necessary. But there should be a robust conversation about its necessity. And in this instance there wasn’t a robust conversation, and Fallujah veterans were kind of thrown out there as a solution to an emerging crisis.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I wanted to make sure that the boots-on-the-ground perspective of the people who actually execute military action was documented, so people can have a more informed conversation.

TWH: A decade ago, on the 10-year anniversary of Operation Phantom Fury, what were you thinking about?

Brennan: Right around the 10th anniversary was just after ISIS had retaken Fallujah. I just remember I really started questioning, “Was it all worth it? What was it all for? Did [1st Lt. Daniel] Malcolm and Faircloth and all the other people who died in that battle, the Iraqis—was it for nothing?”

Ten years ago, I was getting out of the military, and I was just starting to think, to really process that they weren’t just legitimate military targets that I was shooting at.

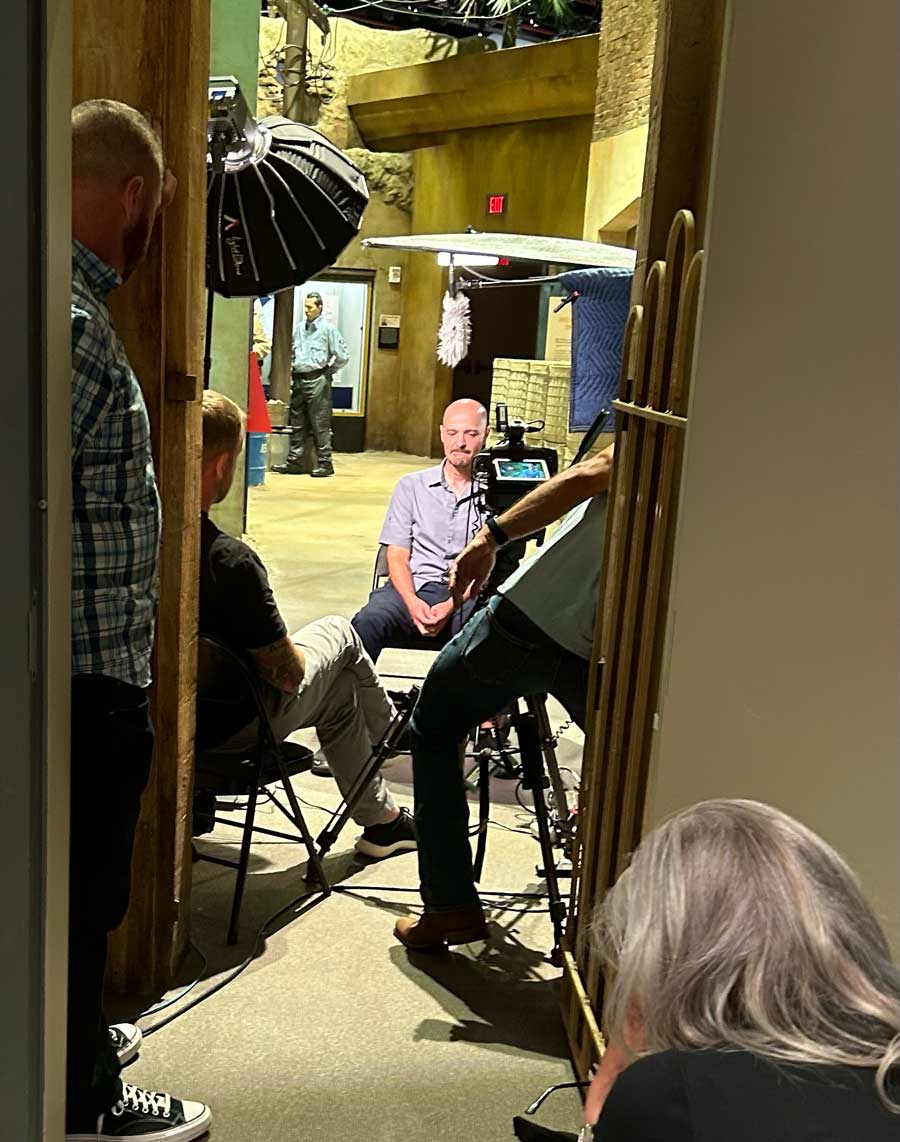

Brennan, seated left, interviews corpsman Reinaldo “Doc” Aponte inside the Fallujah exhibit at the National Museum of the Marine Corps with squad members and mental health specialists there for support. (Photo by Mike Frankel)

I was rebuilding my life as I was getting out of the military, but at the same time, people were rebuilding their lives in Fallujah, rebuilding houses, rebuilding roads, rebuilding government infrastructure. Ten years is where I started to reach a point where I could actually start to kind of process it and think about it and try to make sense of it all.

TWH: Tell me a little bit about your experience reporting out this story.

Brennan: My earliest drafts were just my recollection of specific scenes and elements of the story. And then as I continued to flesh it out, that’s where I was like, “Oh well, this is where [Mike] Ergo was hit. I can talk to him and figure out what the rooftop looked like.” Because all I knew from my perspective for that scene in particular was I was on the second story. But the roof was where all the craziness was. So I had to have those individual conversations with each of the guys for each of the scenes.

Part of what really hurt initially, but has been good in the long run, is I’ve been mad about some things for many years. Learning that I’ve had a wrong memory, or learning additional context about something, or hearing something that gave me closure, was really good during the reporting process. I was able to let go of some of the anger.

TWH: Earlier this year, you brought your squad together for a reunion in the Washington, D.C., area, including trips to Arlington National Cemetery and the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia. Was that the first time you had all come together since the war?

Brennan: We had texted here and there over the years. But a lot of that was really right around the 10th anniversary. We all started saying hello to each other again. [Before that] we all kind of needed our distance and time to process things.

The reunion was the first time that we ever talked about stuff, about what the deployment was like. To hear other people who actually took part in it express some of the same regrets and feelings that I did, it makes you feel less alone.

Brennan put his daughter, Madison Brennan, to work as a photographer, documenting his squad’s reunion this summer. One of the events they attended was a Marine Corps Friday night parade at Marines Barracks in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Trevor Gift)

The other thing we all realized is the survivors’ guilt that we all carry around Bradley [Faircloth’s] death. That became abundantly clear to me. Every single person, regardless of where they were, blames themselves in some way. To actually hear and fill in the blanks made some of the guilt that I carry—I shouldn’t, it’s completely irrational—but it made it feel lighter.

TWH: How did you navigate balancing your own experiences and emotions as a person and a veteran with putting out a journalistic account of your squad?

Brennan: I’ve maintained my objectivity as best as possible as I’ve written this, because I’m too close to say that I’m not biased at all.

The advice—or not the advice, the order—that I got from my squad leader, Sgt. [Billy] Leo, was if you’re going to tell this story, you are going to be brutally honest about what we experienced and not sugarcoat it.

Every one of the Marines and corpsmen and family members that I spoke with, I made that abundantly clear to them, that this was going to be an unsanitized story about our experiences in Fallujah.

The Iraqi voice is missing in the piece. It is. But through the painstaking detail that I think I’ve gone through explaining what we blew up, what we destroyed, the state that we left that city in when we were done, I hope that I’m showing the monumental challenge that Fallujah as a city and Iraqis as a people had to overcome after we left.

TWH: You were on The Daily Show earlier this month on Veterans Day talking about The War Horse and your reporting on Fallujah. What was that like?

Brennan: My happy place is writing a story, wearing a pair of comfy slippers. So being on television is stressful for me.

But Jon [Stewart] was such an empathetic interviewer. What I’m really grateful for is that it wasn’t an interview only about myself and my experiences. What I really don’t want people to see when they read the written piece is that it’s about me. I want to tell the story of the Battle of Fallujah and the story of some of the Marines that were over there. And he gave me the opportunity to talk about Doc, and to talk about what corpsmen and other service members are willing to sacrifice on behalf of the American public.

I think it was exactly the type of conversation that America needs to have on Veterans Day.

TWH: What do you hope people will walk away with when they see the documentary or read the story?

Brennan: I hope that what people see through the brutal honesty and kind of the brutality that I write about, I hope they see it as a cautionary tale.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

I hope they see that service members will be willing to go to war like the American public asks them to. But I hope that when people watch this, they see not only the human impact on the people who have to kick in the doors and fight that battle but also the struggles of the people who have to move back home to wherever that battlefield is, whether it’s Iraq or Afghanistan or Ukraine or Gaza.

America needs to know what it looks like when the dog gets let off the chain, and they need to make sure that it’s a deliberate and thoughtful decision when they choose to do so.

Comments are closed.