The Berlin Wall Would Soon Tumble, Divided States Would Reunite. My Work Was Done.

Editor’s Note: This story was published in partnership with San Quentin News and was written during a writing seminar for incarcerated veterans in April hosted by The War Horse at California’s San Quentin Rehabilitation Center. Tens of thousands of military veterans are incarcerated across the United States, and these stories are intended to shine a light on their unique needs, challenges, and experiences. Learn about the seminar here.

I’d cautiously moved forward some 30 feet in the gloom of salt vapor lights and hulking shapes of tractor trailers and stacks of camouflage when the hair on my neck started to tingle and rise.

The party behind me represented my worst nightmare for the last two decades—avowed enemies who’d lived in my crosshairs and who regarded me just the same. First was the Russian translator. Ten inspectors followed, including four in bearskin caps and three KGB members in polo shirts and faded blue jeans with fat rolls of American money stuffed in their pockets like rebellious teenagers.

A high-ranking member of the Russian Strategic Rocket Forces in a campaign uniform and hat acted as team leader, but the real power was with the four political members, two of them women.

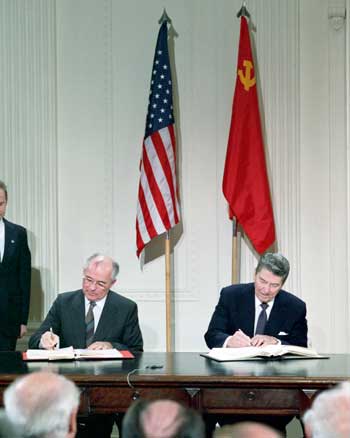

The group comprised the first inspection team of the NATO/Soviet Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force (INF) Treaty. Signed by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev on Dec. 8, 1987, the nuclear arms-control accord would eliminate the countries’ stocks of mobile land-based missiles that could carry nuclear warheads.

I was chief of safety for the U.S. Air Force at the 501st Tactical Missile Wing at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire, United Kingdom.

The slow march continued, its purpose to count the nuclear arsenals—verifying their presence in an operational posture.

That morning, I’d grabbed my briefcase, patted the head of my five-year-old son, Derek, who was dressed in a jumper and shorts for the local infant school, kissed his mother, and said I would be late that evening. I had a busy day ahead.

President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev signing the INF Treaty in the East Room in December 1987. (Photo courtesy of White House Photographic Collection)

I drove from Kingsclere, seven kilometers north to RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire, where the ground-launched cruise missile system was installed in partnership with the Royal Air Force to provide NATO a heavy response to SS-20 IRBMS and 17 divisions of closely positioned armor tanks. Planners speculated Soviet forces, without heavy opposition, were just seven days from the English Channel. Fully deployed, the ground-launched cruise missile system was the heavy opposition.

The walk continued slowly past the transporter erector launchers that faced us to the rear and their impressive, eight-wheel-drive MAN tractors.

The exhaust doors at the rocket discharge end were propped open so the team could count each of the four mounted missiles and keep tabs on the number of transporter erector launchers they observed. On a far wall was a line of X-shaped nuclear weapon warhead shipping containers soon to be put to work. They were light blue in color but of no interest to the inspectors since the treaty only addressed reductions in launchers and missiles. Of course, I knew the KGB was taking account of everything.

Arriving at RAFGC, I squeezed past the women of Greenham Common who lived crowded around the main gate in a tent city, protesting the presence of nuclear weapons in the United Kingdom. They’d been here since before the ground was broken for the ground-launched cruise missile system installation, getting up early every morning to make life interesting as the airmen coming to work ran the gauntlet.

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty was about to give them everything they asked for, but I don’t think they knew it yet. The gate rolled shut behind me, disappointing the women.

A long day lay ahead of me: a final briefing, drilling on what-ifs, and protracted after-action reports. The visitors were slated to depart on their Soviet transport the next morning.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

The walk continued, passing the first flight of four transporter erector launchers. We’d cleared the entrance by 50 feet, and the door opened again to admit the trailing first aid team who’d shadowed us through all the barns. Thereafter, the security team—four of our intrepid flight security personnel—kept a respectable rearguard as we advanced flight by flight until all six were surveyed.

As the count came to a close, I reflected on my own career, first as a young lieutenant in Strategic Air Command’s ICBM operations where I’d spent hours, days 30 feet underground in a Titan II launch control center in the desert of Arizona. We spent days ready to execute the 58-second countdown of the nation’s most powerful weapon, capable of responding with lethality to an attack by Russia or China’s nuclear forces. The threat of counterforce proved its effect during the Cold War.

A view from above the silo housing a Titan II missile at the Titan Missile Museum in Green Valley, Arizona. (Photo courtesy of the US Air Force.)

Later, I watched from the rocky shores of Sheyma as RC-135s plowed their way through fog and slough to arrive over Kamchatka where Soviet ballistic missile tests told the tale of Russian power.

In the 1980s, the tanks and nuclear missiles of the USSR crowded against the Iron Curtain needed a counterforce. The ground-launched cruise missile was that counterforce; it had done the trick. The Soviet SS-20 would draw down, the tank divisions would back off the line, and the ground-launched cruise missile system would stand down. For a time, at least, the world would be a safer place.

As these thoughts ran through my mind, I realized my work was done. The Berlin Wall was soon to tumble, border wire in Romania would no longer contain refugees from the Soviet hegemony, and divided states like Germany would soon reunite. I was just one of thousands who had made this happen, but my part was done. I confirmed in my mind my decision to retire and seek work in the civilian world.

But the count was not finished. We cleared the last flight equipment and made our way, still in line, fur caps intact, through the last door, climbed back on the yellow school bus transportation had assigned to us, cleared the last security check, negotiated the double fence topped by razor wire, and drove slowly to the visitors lodging.

It concluded in all of 45 minutes. The debriefing completed, I walked across the deserted main base, cleared for the convenience of the inspection party’s freedom of movement. To my surprise, I saw the Soviet team’s military chief and his interpreter on a walkaround of the deserted Base Exchange. As our paths crossed, the interpreter suggested we stop to talk.

I agreed, knowing I would be required to report the contact.

The Soviet colonel began talking in a formal way, as if making a banquet speech. His soliloquy seemed memorized and apparently well-practiced, as well as the interpreter’s translation. The event puzzled me. I wondered if this was a rehearsal for a more formal occasion or the frustrated regurgitation of the prepared remarks that would not have the chance to be heard. The speech opened with the standard welcome and accommodation but deteriorated into mild recrimination of the West for antagonism against the Soviet Union that had necessitated the Iron Curtain and buildup of Soviet forces.

Wasn’t it too bad, he said, that America had to go to all the expense of building the ground-launched cruise missile system and installing it to the dismay of the NATO countries. Wouldn’t it be better, he said, if we all just got along?

My blood was up.

One of two keys that would be turned by a crew commander if a missile had been launched from the launch control center inside Missile Site 8. The indicators to its right would have lit up as the launch sequence began. (Photo by Katie Lange, courtesy of the Department of Defense)

His matter-of-fact description of a world sharply divergent from the one I knew unsettled me. I looked around; no one was in sight. In as pleasant a tone as possible, I suggested that missiles and tanks arrayed against the West were sure indications that the fault did not belong entirely with the West. Also, I continued, we certainly would have spared the cost of the deployment had the obvious antagonism allowed a different approach.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

I pointed out that we were relieved that the nuclear standoff had ended, allowing me to go home and live the life that America affords. I could have mentioned, but didn’t, that I hoped the bounty his comrades had purchased from the exchange would satisfy the lust for things that Western productivity had afforded.

He blinked in surprise at my unanticipated rebuttal.

After more small talk, we departed friends. It was the last I saw of him and his team, except in the distance the next morning as the crew of their airline transport struggled to load the sea of shopping bags flooded around the aircraft. Eventually, it all disappeared on board along with the team, and we all waved a send-off as the liner accelerated down the runway and retracted the gear.

I wished them well. The count was done.

Back at home, Derek was happily playing with this Tonka toy on the living room floor, counting the blocks he could load in the bucket.

This War Horse reflection was written by Ray Melberg, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.