‘Post’ reveals why Israel held back from striking Iran’s nuclear sites

On April 13-14, 2024, Iran changed the Middle East forever, ending a decades-long covert shadow war with Israel by openly and directly attacking Israel with 180 ballistic missiles, 170 drones, and dozens of cruise missiles.

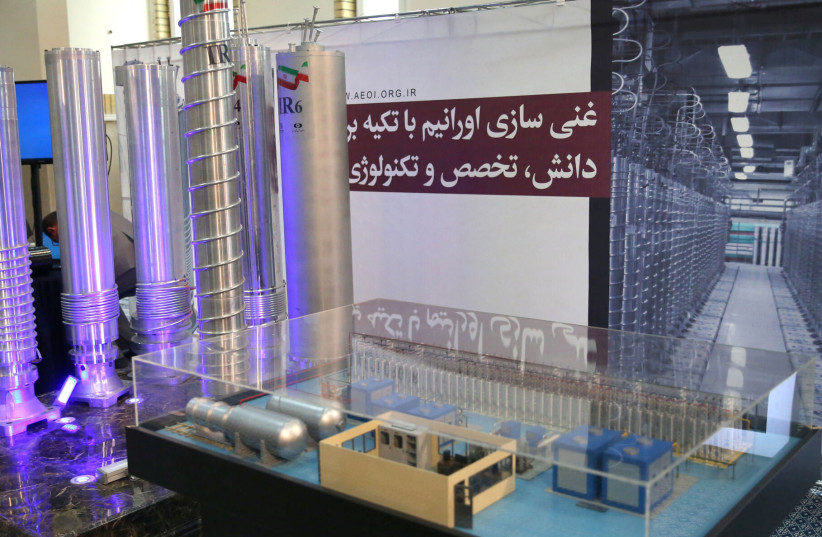

Israel responded on April 19, 2024, by attacking one S-300 anti-aircraft defense system, which was protecting the Islamic Republic’s nuclear facility in Isfahan.

The Jewish state never seriously considered attacking Iran’s nuclear sites in April 2024 like it did in October 2024, but that first direct round between the sides set the stage for the more dramatic follow-up.

Although that end result is well-known, The Jerusalem Post now reveals for the first time the full extent of the debates between Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, then defense minister Yoav Gallant, and then IDF chief Herzi Halevi, then war cabinet ministers Benny Gantz and Gadi Eisenkot, and Mossad Director David Barnea.

Similar but evolved debates came into play in October 2024 after Tehran attacked Israel directly a second time, this time with over 200 ballistic missiles on October 1, 2024.

This time a similar cast of characters debated the issues, but Gantz and Eisenkot were already out of the picture having exited the government on June 9, 2024.

And then there was a third round of the least reported debates after October 26, 2024, but before Donald Trump entered office, replacing Joe Biden as US president.

Here, Gallant was also mostly out of the picture, given that he was fired by Netanyahu on November 5, 2024, leaving Netanyahu along with defense chiefs Halevi, Barnea, and some of their top advisers.

What was radically different in the post-October 26 debates was that suddenly Israel knew it could pulverize Iran’s nuclear facilities almost at will, whereas until then there had been concerns about whether the Israeli air force could sufficiently outplay Iran’s S-300 anti aircraft defense systems for long enough to hit enough Iranian nuclear targets enough times to do the job.

And yet Israel held back.

A limited counterstrike

Although many of the above key decision-makers evolved in their views during the debate about how harshly to respond, roughly speaking, in April 2024, Eisenkot and Gantz were the most concerned about keeping Israel’s counterstrike limited so as to avoid an escalating series of strikes and counterstrikes.

Netanyahu was concerned about overreacting as well, but was sounding some greater readiness to take risks in counterstriking Iran than Eisenkot and Gantz. This was a shift with Netanyahu being more confident about using dramatic military force, given that Gantz had been more ready to invade Gaza faster and harder in October 2023 and Khan Yunis in December 2023 than Netanyahu.

Eisenkot had been ready to use strong military force in October 2023, but already wanted to continue hostage exchanges in November-December 2023 without rushing into Khan Yunis.

Barnea, who is often the lead on Iran issues in the defense establishment, was in favor of a strong counterstrike, but it was difficult to pin down exactly as he wanted US support for Israel’s retaliation choice and for continued broader war goals.

Gallant and Halevi were the most outspokenly aggressive about striking back.

At some point, Netanyahu joined Gallant and Halevi for striking Iran’s S-300 anti-aircraft missile system protecting its Isfahan nuclear facility, and eventually, even Gantz supported this strike, though Eisenkot remained opposed.

After Iran’s October 1 attack, positions had already shifted somewhat.

Gallant and Halevi still wanted to be relatively aggressive, but were much more closely aligned with the US and ready to avoid attacking Iran’s nuclear program in order to keep Washington on board.

In contrast, Netanyahu was becoming more aggressive in his approach to the war across the board and also more ready to defy the Biden administration, given that election day was only a month off and Trump was favored in the polls.

Still, Netanyahu wanted the US and its allies to help Israel defend itself from any potential additional rounds of Iranian ballistic missile attacks, and part of that was also expressing gratitude to America for helping protect the Jewish state from Iran on October 1.

US authorization

Also, Israel wanted US authorization for flying over certain Middle Eastern countries on the way to striking Iran.

Barnea continued to support a somewhat aggressive approach to the Islamic Republic, but always emphasized the need for US buy-in as a restraining factor.

This is how Israel arrived at the decision to strike the four remaining S-300 missile defense systems in Tehran, as well as more than a dozen other air defense and ballistic missile production targets, as well as one nuclear-related target at Parchin on October 26.

The impact of Israel’s attack was to reduce Iran’s ballistic missile production capacity from manufacturing 14 new missiles per week to one per week, with a one to two-year recovery time.

In terms of the impact on Iran’s radar, tracking, and air defense capabilities, Israel’s attack left Iran’s nuclear program completely vulnerable compared to the air force’s capabilities.

Why then didn’t Israel immediately rush out the fateful strike on Iran’s nuclear program on October 27, or in the limbo transition period between October 26 and inauguration day of January 20?

Especially after election day, Biden was a lame duck who could only have penalized Israel so much for defying his will.

The answer actually lies not with Iran, but on two other fronts: Hezbollah and Hamas.

Even if Israel had taken out Iran’s best chance of competing in a heavy exchange of fire between the countries, the Jewish state was still under heavy fire on October 27 and after US election day.

In the North, around one-third of the country was being rocketed by Hezbollah hundreds of times per day, with some rockets also getting to central Israel. True, Israel was overwhelmingly “winning” the exchange, but the country could not indefinitely sustain the level of rocket fire that Hezbollah could keep up.

In the South, Hamas no longer had such capabilities, but still presented a threat, which made it hard to convince southern residents to return to their homes closer to Gaza, and the terror group still held around 100 hostages, half of whom were still alive.

Also, at the time, Israel was facing nearly daily ballistic missiles from Yemen’s Houthis, which each time sent millions of Israelis in the Tel Aviv and central Israel corridors into their bomb shelters.

Removing other threats

In order to be ready for a potentially broad military campaign with Iran, which could involve multiple rounds of exchanges of many hundreds of ballistic missiles more than before, top Israeli officials wanted to remove other threats from the board.

It took until November 27 to get a ceasefire with Hezbollah, and even then, significant Israeli attention was focused on keeping US support for framing the post-war order in Lebanon. This was key to ensure that the Lebanese army would block Hezbollah from returning to southern Lebanon and that the IDF would be free to strike the terror group each time it violated the ceasefire deal.

A deal with Hamas for returning some hostages and a ceasefire did not occur until January 19, the day before Trump’s inauguration.

And there was enormous pressure for another such hostage deal after the last deal had occurred way back in November 2023.

Once again, Israel needed both Biden and Trump’s support to seal the deal, and this might not have happened if Jerusalem had gone head-to-head with Tehran.

There are also some who believe Netanyahu only wanted the Hamas deal to happen once Trump was taking office, so that he could frame the post-ceasefire situation in terms of dismantling Hamas – and not a Palestinian Authority-led Gaza with Hamas still intact in the background.

In any event, the Hamas deal also took off pressure from the Houthis, and before Israel went back to war with Hamas on March 18-19, America was already striking the Houthis far more seriously to keep them busy on the defensive and less on the offensive.

Most top Israeli officials believe progress on these issues could not have happened, and also the 33 hostages who Hamas returned to Israel over January-March could have been endangered, if Israel had launched a larger war with Iran during the Biden-Trump transition.

Also, top IDF and Mossad officials believed that Trump would be open to a full attack on Iran’s nuclear sites at some midpoint in 2025, such that there was not necessarily a rush.

Generally speaking, Israeli officials have felt blindsided by Trump’s turn from calling on Israel to strike Iran’s nuclear program in October 2024, to waving off their attack plans in 2025, and seemingly barreling forward toward a new, highly flawed nuclear deal.

Had Israeli officials realized that such a scenario was just as likely as green-lighting an Israeli attack or coercing Iran into a much tighter nuclear deal, some might have favored launching an attack during the Biden-Trump transition.

Yet, some, even looking back, would say that the strategic importance of obtaining ceasefires with Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Houthis was worth the price of temporarily missing the window to attack Iran.

According to these sources, Israel has prevented Iran from getting a nuclear weapon using covert means for decades, and it can again. Further, if Iran really does try to take advantage of a new weak deal to break out to a nuclear weapon, the air force could still step in in time to strike.

Finally, though no Israeli officials are saying this out loud yet, even a mediocre nuclear deal could buy Israel time by setting Iran’s nuclear progress back for the first time since 2019, when it threw off the JCPOA restrictions.

This is far from the ideal scenario of using Iran’s relative defenselessness post October 26 to smash its nuclear program with a giant military strike, but it may still be a better result than any deal the Biden team could have gotten before Israel put Iran directly in its crosshairs.

Comments are closed.