I Left My Platoon a Day Early. I Listened as the Viet Cong Killed My Replacement

My platoon was about 100 miles from Pleiku City, searching for the Viet Cong within South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The mountainous elevation offered little protection from the humid air that left us staggering as if intoxicated.

I was the platoon’s forward observer, and March 31, 1968, marked the end of my fifth scary month stationed in South Vietnam. In 48 hours, I would begin a seven-day leave in Bangkok.

The resupply chopper would bring in my replacement, Frank, and fly me out. I was excited about traveling to Bangkok after listening to stories from guys who took their leave there: days of girls, bars, and beer.

The battalion XO requested the platoon’s resupply a day earlier, so I got to leave a day ahead. When I relayed the good news to the platoon lieutenant’s aide, he gave me a typical military reply: “Lucky you, asshole.”

But first we had to march to the landing zone, a miserable nine hours of tramping up and down hills, spending a hellish part of the journey trekking through swampy areas full of mosquitos, snakes, blood-sucking leeches, and unbearable humidity.

Once there, the resupply chopper could land, pick me up and drop off Frank, and unload the supplies.

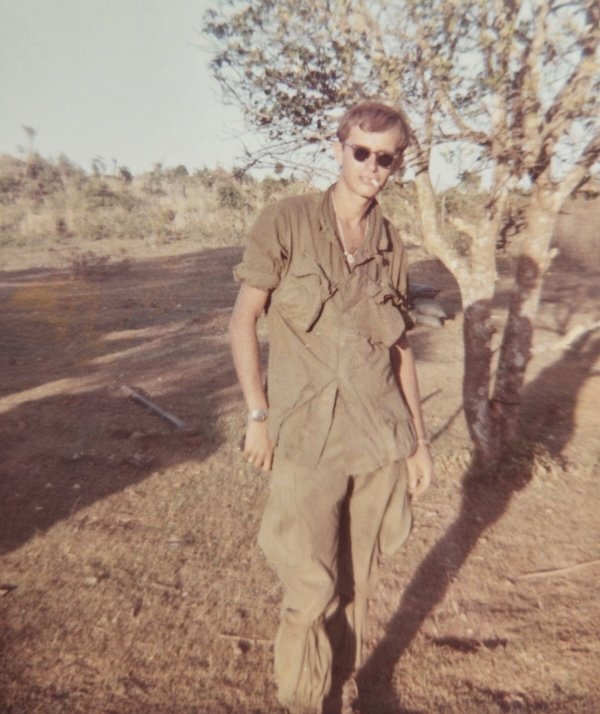

The author taking a smoke break while setting up camp in Vietnam in 1969. (Photo courtesy of Stanley Ross)

Upon reaching the campsite location, a patrol scoured the surrounding area, searching for recent signs of the enemy near the camp’s perimeter. I didn’t join the patrol because the lieutenant wanted to ensure that I was packed and ready to go.

The patrol leader reported there were no recent signs of the Viet Cong close by.

Early the next morning I grabbed my backpack and weapon and headed to the landing zone pronto. I gave the aide my cigarettes and packs of instant coffee.

The resupply choppers landed just as I arrived. The pilots signaled with a thumbs-up and I waved to the guys while the chopper lifted off, the treetops quickly fading into the distance. This would turn out to be my last goodbye with some of my friends.

The artillery base was a few miles away. I prepped my cot with an inflated air mattress and poncho liner, preparing for a night’s stay before flying out the next morning.

Back at my platoon, Frank had reported hearing frequent noises around three sides of the platoon’s perimeter. Everyone concluded that the noise originated from a large group of monkeys passing by, though prior experience showed that monkeys were often quiet during evening hours.

I later learned that the lieutenant did not order the platoon to dig foxholes because they didn’t see sandal prints, broken tree branches on the nearby trails, or other signs of recent Viet Cong activity.

Frank and the lieutenant asked that artillery units fire precautionary shots into the surrounding areas. This was a common safety practice used by American units in the field to locate or frighten away any Viet Cong guerillas or North Vietnamese soldiers who might be lurking nearby.

They fired high explosive shells. Unfortunately, the shells fired well beyond the location of the noise and didn’t hit the enemy that we later learned was inching closer.

Creeping up to the platoon’s perimeter was a common tactic when the Viet Cong prepared to attack an American campsite. Once they infiltrated the perimeter, Americans would be reluctant to spray artillery fire, in fear of hitting other American troops.

I awoke early the next morning, startled by the sound of people rapidly moving and yelling. Outside my tent, I was surprised to see South Vietnamese artillerymen preparing the 105 mm artillery guns. There was no gunfire, and their weapons were pointed up, so I knew it wasn’t the artillery base that was being attacked.

I ran to the command bunker for an update on my platoon.

Listening to the nearby radio, I could hear Frank screaming for immediate artillery support and requesting the assistance of helicopter gunships. Frank sounded frightened—his voice quivering, anguished, and panicky as he reported an attack from a large Viet Cong force. My platoon was being overrun.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Hearing Vietnamese voices over the radio meant that the enemy had penetrated the perimeter. The sound of shots firing from M16s along with the rapid firing of an M60 machine gun matched by the rattle of AK-47 gunfire was unnerving.

The request for artillery support came too late. With the enemy inside the perimeter, firing artillery would injure Americans along with the Viet Cong.

Ron Puls and Stanley Ross with two South Vietnamese soldiers in 1968. (Photo courtesy of Stanley Ross)

Frank began screaming, “They are all around us!”

An instant later he yelled, “I am hit, I am hit. Holy shit!”

Those words haunt me to this day.

The growing sound of Vietnamese voices indicated that they were closing in on Frank’s position.

His voice then rang out: “I am shot again. I am dying.”

A quick burst of gunfire silenced Frank and deadened the radio.

I later learned that the Americans who survived the initial attack scattered after the Viet Cong penetrated the campsite. Troopers apparently ran helter-skelter to avoid crashing into Viet Cong.

Half the platoon survived and escaped to a defensive position, including two walking wounded. The survivors hunched along the protective barrier they constructed from tree limbs, waiting for another attack.

After an hour passed with no assault, the lieutenant convinced the captain that the chances of another assault were negligible.

The choppers were then sent out. One of the choppers took me to Pleiku City en route to Bangkok to start my vacation. The other resupply chopper brought the wounded and dead Americans to the medical center in Pleiku City.

The images of the lifeless bodies consumed my thoughts. I kept thinking about Frank’s anguished cry for help. I imagined him lying on the ground with his life ebbing away towards death.

To this day, I frequently replay the sound of Frank’s voice, the voices of the Viet Cong, and the sound of the gunfire.

Why did I survive and Frank die? I’ve often wondered. I can never answer that question.

My guilt was overwhelming. Frank’s last moments tormented me. I visualized him enduring the agony of his wounds, though I couldn’t picture myself in Frank’s place. The picture disappears almost as soon as the image begins forming.

Still, I shook as I contemplated the thought that Frank’s death could easily have been my destiny. I have often thought about Frank’s family and their mourning. I was thankful that I did not suffer Frank’s fate. My mother would have been devastated; I was her only child.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

I pictured the faces of the other deceased Americans. Men I knew were dead, lost to me and their families forever.

They were not strangers to me. These were men I ate with, joked with, marched with, and fought with for months. People bond fast out in the field, where it is life and death.

In the aftermath, questions gushed from my mind: Why was I ordered to leave a day early? Why did the lieutenant choose to forgo digging foxholes?

The only answer I’ve drawn is that life is precious and I must guard it with my entirety. Simple decisions can lead to drastic consequences. In war, mistakes happen. Sometimes the end result is a visit from the Grim Reaper.

This War Horse reflection was edited by Kim Vo, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Kim Vo wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.