Adventure, Tenacity, and Merit Badges—How the Boy Scouts Prepared Me for Military Service

No two American institutions have had a more positive impact on my life than the Boy Scouts of America and the U.S. Navy. When I was in first grade at Hazeldale Elementary in Oregon I saw other students wearing their blue Cub Scout uniforms to school and I wanted to be part of that club. Everything they did seemed exciting, adventurous, and FUN. Go camping! Race Pinewood Derby cars! Learn new skills! But for various reasons, it didn’t happen.

Finally, in the sixth grade, an age when you are too old for Cub Scouts and a lot of boys started to leave the program, I joined my first Boy Scout troop. I quickly discovered I had a lot to learn. All the boys had been in the program for years and had skills and knowledge, while I didn’t even have a proper uniform yet.

Within the first few months, I attended the “district camporee” on Sauvie Island near Portland, Oregon. It was a large endeavor with more than a thousand boys and adult leaders from the local area. The National Guard provided some logistical support for the event. It was my first time being around uniformed military and I was soaking up the experience.

Many of my adult Scout leaders were veterans, and I enjoyed listening to their stories of travel, adventure, danger, and even military bureaucracy. It was a fun way to get to know my leaders and learn about new worlds.

Perhaps the most memorable leader I met was WWII veteran Karl Bierly. Karl was the first WWII vet I had ever personally known. He was always upbeat and exceptionally modest about his service in Europe. To me it seemed like the “biggest thing ever” and to him it was just “something I had to do so I could get back home.”

I’m not going to sugarcoat it, my first year in the Boy Scouts was tough. The older boys took turns hazing me, making me fetch imaginary “bacon stretchers” and “sausage peelers” for breakfast, and taking me on “snipe hunts” when it got dark. I did not have any proper equipment. I was told I needed to start earning skill awards and merit badges and I didn’t even know what they were.

But I persisted. I mowed lawns and picked strawberries to earn money so I could buy hiking boots, a backpack, pocketknife, and other gear. I started working on my progress awards and eventually earned my Tenderfoot and then Second Class rank.

In 1979, Troop 267 spent a summer week at Camp Spirit Lake in Washington. Just getting to the camp was a nine-mile hike that I dreaded. Scoutmaster Mike Davis challenged me: He said if I could complete my canoeing merit badge at camp, I could skip the hike back out and paddle across the lake with him at the conclusion of camp.

This might sound simple, but I was so inept I couldn’t even pass the swim test at Camp Baldwin the previous summer. Not to mention that Spirit Lake was filled with snow runoff that left water temperatures in the 40s. Completing this challenge was a terrifying prospect.

The author earned his canoeing merit badge at Boy Scout Camp Spirit Lake in 1979. (Photo courtesy of David Chetlain)

But somehow I found enough grit and moxie to pass the swim test and complete my canoeing merit badge. I probably smiled with every paddle back across the lake that summer. I felt I could accomplish anything I set my mind to.

The following summer I went to Brownsea-22 leadership training at Camp Clark on the Oregon coast, where I survived another week of tough challenges. Many times during my Navy career I leaned on what I had learned from that week.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

By then I had earned my Star Scout award and was feeling confident about my Scouting experience. I got to represent the Columbia Pacific Council at the 1981 National Jamboree that was held at Fort A.P. Hill (since redesignated as Fort Walker) in Virginia.

About 30,000 Scouts from across the globe descended on this Army installation for the thrill of a lifetime. After touring the surrounding area for 10 days, we pitched our tents at the fort and participated in Jamboree events.

The Navy brought its balloon team to the 1981 National Jamboree. (Photo courtesy of David Chetlain)

The Army was everywhere, but all the other services were also represented. The Navy’s balloon team came. The Army Golden Knights parachute team did a jump. The Air Force had displays. Every day brought new adventures to conquer and new people to meet.

The obligations of high-school life inevitably slowed my Scouting experience, and I stalled at the rank of Star Scout for more than two years. But I knew that I wanted to earn my Eagle Scout Award and it had to be completed before I turned 18, so I bore down.

First up was knocking out all the remaining merit badges followed by my Eagle Scout Service Project to restore the historic Jenkins Estate in Beaverton, Oregon. Though still a teenager, I organized 25 people and we cleared trails, removed blackberry bushes, and fixed the caretaker’s house.

Along the way I had enlisted in the Navy’s Delayed Entry Program the summer I was 17. Three months later I earned my Eagle Scout Award, and then my Bronze Palm the day before I turned 18.

Six months later I was in the naval training center in Great Lakes, Illinois. While there is no direct correlation between the Scouts and the military, many of the principles I learned in my six years of Scouting directly transferred to my military success. I already knew what a chain of command was, and I knew how to seize initiative and take responsibility for my actions.

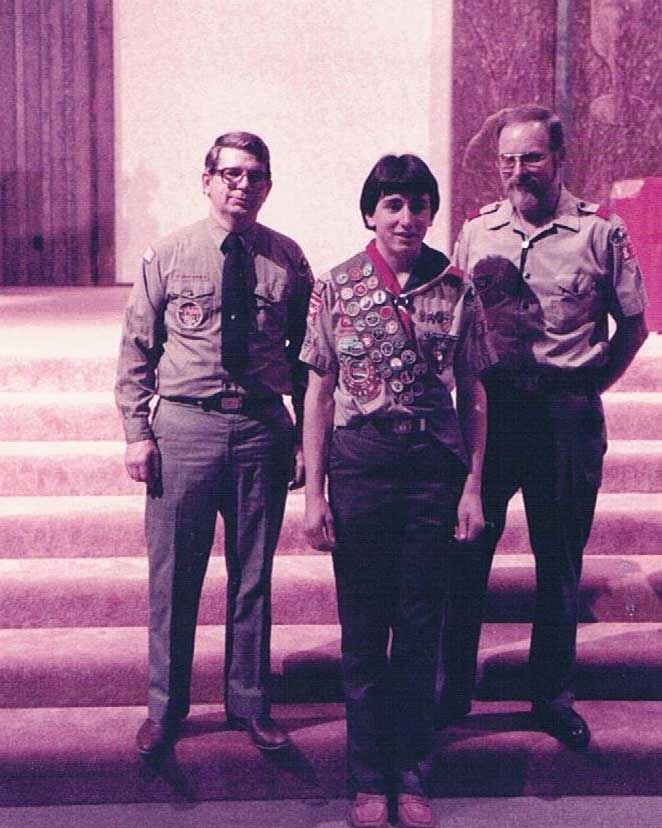

The author at his Eagle Scout ceremony with scoutmasters Mike Davis (left) and Francis Mijo. (Photo courtesy of David Chetlain)

The Boy Scout Law outlines 12 core principles for Scouts to live by: trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent.

I often referred to these principles in my daily Navy life and not once did they ever fail me, though I often failed them.

As a young adult, I felt compelled to give back to the organization that had done so much for me. Once I was stationed at Naval Submarine Base Bangor, Washington, I volunteered as an assistant scoutmaster. My submarine duty obligations meant that I could only be present about five months a year, but I attended meetings and events as my schedule allowed.

In 1991, my commanding officer at the Navy Recruiting District in Portland said that I had the perfect background to become the youth programs coordinator. In this role I was the Navy’s liaison to youth organizations in a five-state area. Among other duties, I attended Boy Scout meetings, chaperoned Sea Scouts, coordinated tours of Navy vessels for youth organizations, and did a lot of public speaking. There has never been a more perfect role for me.

The Navy granted an advanced enlisted rank to E-2 or E-3 to anyone who had accumulated a modest amount of college credit. To my mind, the three-plus years of effort required to earn an Eagle Scout or Girl Scouts Gold award was more significant than a year of community college. So I submitted a proposal that would grant advanced enlisted rank to any Navy enlistee who had achieved those Scouting awards.

My proposal turned into policy in 1993, just a few months before I was discharged. It still stands today and helps improve the Navy’s quality of recruits while also recognizing the young people who earn these Scouting awards. I consider it my greatest legacy.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Historically, people with Scouting experience are overrepresented in the military. In the recent U.S. Air Force Academy’s graduating class, 20% were Scouts and about 10% of the cadets had earned the Eagle Scout or Girl Scout Gold award. This is a remarkable number when one considers that only about 6% of all Boy Scouts go on to earn Eagle Scout.

There are reports that some are pressuring the Defense Department to reassess its relationship with the Scouts, with critics complaining that it’s “woke” since it now allows girls and calls itself Scouting America. I don’t know about woke, but I know it awakened something in me.

When I earned my Eagle Scout Award, my first scoutmaster, Mark Witham, wrote me a letter recalling my early days when I was truly a struggling “tenderfoot.” Since then, he noted, “You have demonstrated that Scouting is a commitment to fulfilling your potential by continuing to learn, to lead, and to participate.”

I have spent the rest of my life trying to live up to what Mark saw in my 12-year-old self.

This War Horse Reflection was edited by Kim Vo, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mollie Turnbull. Kim Vo wrote the headline.

Comments are closed.