Their Bombs Destroyed–and Still Threaten–Villages. Vietnam-Era Veterans Are Going Back to Help and Heal Veterans are struggling with guilt after USAID cuts impact cleanup programs. ‘We have a responsibility to help pick up this garbage’

High in the mountains of Northern Laos, nestled in the Plain of Jars, rests the small village of Laht Saen. Its residents are mostly farmers growing rubber trees, peppers, some pigs, chickens, and small quantities of rice.

Like so many other villagers in Laos, the people there live in a constant state of suspense. At any moment, the ground beneath their feet could explode.

Though the United States military left Laos after the CIA’s “secret war” ended in 1973, the 270 million bombs they dropped did not. Today, more than 79 million unexploded ordnances remain hidden in the shallow earth there, ready to maim or kill anyone who stumbles upon them.

Understanding this constant peril brought U.S. Army veteran Don Super to Ban Laht Saen in 2023 from his remote ranch in Washington state, where he has struggled for decades with his part in the legacy of destruction the U.S. military left behind. Like many fellow veterans, he had returned to help a village—and himself—heal.

It’s an obligation felt deeply by many veterans who fought in Southeast Asia. But this spring, as the U.S. marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, veterans like Super are struggling with guilt again over the Trump administration’s sweeping cuts for international aid that funds many of the programs that have helped normalize relations and clean up the war-torn region of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

The funds the U.S. government has given in the last 30 years is “just chump change” compared to what is needed to finish the job, Super said. “But at least it’s an admission on our part that we have a responsibility to help pick up this garbage.”

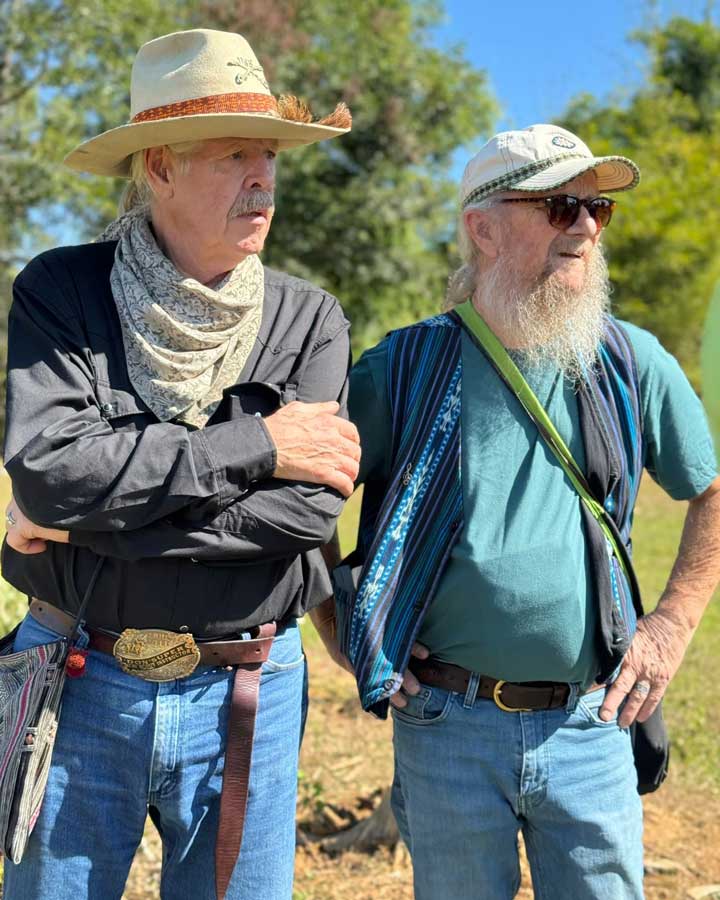

During a visit in 2023, Super worked alongside a small team of engineers and scientists from the U.S.-based environmental consultancy firm Aqua Survey, clearing mines from a patch of land in the village. He stood out like a caricature of an American cowboy with his bushy mustache, a large belt buckle over his blue jeans, and a braid of brown-white hair sprouting from beneath his Stetson hat. Upon this purified ground, the cowboy and his friends had planned to build a school for four to six year olds.

“I didn’t really do much,” Super insisted in a phone call with The War Horse. “I followed along while the experts cleared mines and then helped dig a footing for the building.”

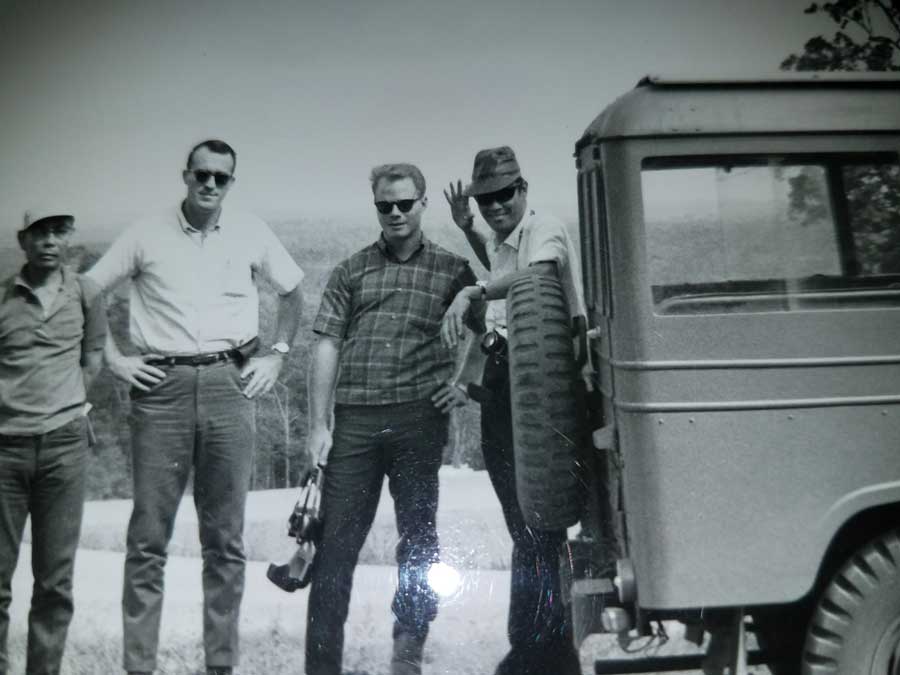

Don Super, second from left, and fellow veteran John Jones, far left, tag along with workers from the U.S.-based Aqua Survey, detecting mines at the site of a school construction project in Laos. (Photo courtesy of documentary film Collateral Damage)

His presence, however, left an impact. When the school was finished, Super was told it was to be named in his honor. Overwhelmed by remorse, the veteran refused. He couldn’t tell them why.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

The United States spent $17 million a day bombing Laos during a nine-year campaign that ended in 1973. From 1969-70, Super was a signal intelligence specialist stationed at Ramasun Station, Thailand, identifying civilian structures and providing coordinates for rescue missions and bombing runs all over Laos. He remembers in December 1969 receiving a transmission about a confirmed “hit” with scores of reported casualties. The target, which he said he personally labeled as a civilian object not to be engaged, was a school.

There are few official records of the deadly airstrikes during the CIA-led war, but historians have shown that the relentless bombings killed tens of thousands of Lao people, mostly civilians. One of those attacks particularly sticks with Super. He had no role in the bombing but every time he goes back to Laos Super visits the site of what’s known as the “Tham Piu Tragedy,” where, according to eyewitness accounts, historians, and a memorial plaque at the site, 374 men, women, and children sheltered in a cave were killed by a single U.S. airstrike.

“Working on building a new school has helped me begin to forgive myself,” Super said, “but I’m never going to share that history with the people who live there; it’s too shameful.”

Super, who turned 78 last month, sees his participation in building the school and similar efforts to clear unexploded ordnance as a minuscule part of a much larger karmic return for veterans and the entire United States.

“I never want to be thanked for my military service,” he said. “I’d rather be thanked for the work I’m doing today.”

‘You’re Going to Get Us Killed’

When the Trump administration announced plans in March to all but scrap USAID, it left hundreds of programs to salve the wounds of American foreign wars scrambling to hang on.

“It is the United States government’s responsibility and moral obligation to clean up the messes its military has made in these places,” says Mike Burton, a former U.S. Air Force officer and pilot who served in Laos during the secret war. “Abandoning that obligation is shameful and makes the countries we claim to support question whether or not they should trust us.”

Before the agency was essentially dismantled, USAID provided assistance to 130 countries, according to a report by the Congressional Research Agency. In terms of dollars spent in 2024, the foreign aid to Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos combined represented a mere .02% of the federal budget. This financial support not only funded programs that cleared land mines and cleaned up contamination from Agent Orange, it also promoted economic development, expanded access to medical services and education, and prevented human trafficking.

Mike Burton, second from the left, was a U.S Air Force officer whose job during the war included winning hearts and minds in exchange for intelligence. (Photo courtesy of Mike Burton)

Across the globe, the cuts have already slashed tens of billions of dollars in funding from about 5,200 programs once supported by USAID. President Trump’s proposed upcoming budget goes deeper, slashing other international affairs and development agencies and programs.

For Burton, it feels personal. During the war, he had been assigned to the 56th Air Commando Wing in Thailand as an “area regional specialist.” The 56th was heavily involved in interdiction warfare against the Ho Chi Minh Trail that ran through Laos. Though based primarily in Thailand, Burton also operated from Lima sites—small airstrips and covert installations that dotted the mountains and jungles of Laos. He trained Thai Air Force pilots to use American aircraft and flew night missions in A-26 Nimrods, dropping bombs over Laos, but officially, his job was winning hearts and minds in exchange for intelligence on the enemy.

“[In] one of the villages I was in very early on, the head man there was a school teacher. … I asked ‘What can we do for you?’ And he said, ‘You can leave. This isn’t our war; you’re going to get us all killed.’”

A few weeks later, Burton was hitching a ride on an O-1 Bird Dog airplane between Air Force Bases in Thailand when they responded to an all-call distress signal: An occupied village in Laos was being attacked, and American special guerrilla units on the ground were pinned down by heavy mortar fire.

“We landed, and the [pilot] told me to go see what I could do,” Burton remembers. “I thought, ‘I’ve been here before.”

Then he discovered the body of the village leader who had urged him to leave just weeks earlier.

“The Pathet Lao or North Vietnamese Army had killed him in a very awful way,” Burton said.

“That’s when everything went sideways for me. I thought, ‘What the hell are we doing here?’”

Since then, Burton has dedicated much of his life to mending the wounds he and so many others left behind in Southeast Asia.

He currently serves as chairman of the board of Legacies of War, an advocacy group that has fought to secure U.S. government funding to clear bombs and mines while raising awareness about unexploded ordnance. The advocacy paid off in 2016, when the Obama administration raised U.S. funding for bomb clearance and victim assistance in Laos from $15 million to $30 million a year.

Legacies of War’s work, in partnership with the Laos military and organizations like the United Kingdom-based Mine Advisory Group, continued temporarily this spring, but many obstacles stood in the way.

“The local [Laos military] troops and MAG staffers there said they would continue to go out in the field where they’d been approved to go for demining, but they can’t get the equipment out there,” Burton said in late March. “They don’t have any money to buy gas.”

At the school dedication, Don Super, third from the right, is honored for inspiring the project. (Photo courtesy of Ken Hayes and the documentary film Collateral Damage)

Restoring Balance

In April 2024, the kindergarten at Laht Saen opened for students. The entire town gathered to celebrate. Despite Super’s reservations, a sign of gratitude welcomed visitors: “This school was inspired by Don Super, who is dedicated to helping the Lao people.”

Super attended the dedication with his wife, Lorah, and their daughter, Lillian.

He and members of Aqua Survey were brought before the village’s elder monk to perform a ritual to restore balance to the soul, a rite known as baci. They were bound together at the wrist by white cotton strings to call back the spirits of the dead and restore harmony. It marked a new period in the life of the village, and in Don Super.

“But this wouldn’t have been possible without someone who wasn’t there that day,” Super later said.

Don Super and John Jones met in the 1980s and have helped each other deal with their guilt over their roles in the wars in Southeast Asia. (Photo courtesy of Ken Hayes and the documentary film Collateral Damage)

That person was John Jones, another U.S. Army veteran. The two became acquainted while working in the forests of Washington state in the 1980s. Super had gone off grid to “try to figure things out” and made a living outfitting pack mules and horses for trail workers and loggers. Jones led a summer program for at-risk youth, cleaning up the trails in the Pasayten Wilderness.

As part of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division during the Vietnam War, Jones patrolled the Cambodian border to ensure no enemy supplies crossed during the tail end of the Tet Offensive.

“I was involved in a lot of operations,” said Jones, 74. “I witnessed the constant bombings and napalming. When you see things like that, you leave a part of yourself behind.”

He remembers the thundering echoes of bombing runs he heard across the border during his deployment and had heard rumors of similar operations going on deep into Laos. On a mission in the spring of 1969, Jones lost his left eye when an RPG struck the ammunition pile in his assault vehicle.

In 2016, Jones had returned to Cambodia to see what the war he’d fought had left behind. With the help of an interpreter and guide, he connected with a Buddhist monk in a small village outside of Memote, Laos.

John Jones was a machine gunner on an armored personnel carrier in 1968 during the Tet Offensive. (Photo courtesy of John Jones)

“The monk introduced me to a former VC soldier, a local leader, who had been wounded about the same time I was,” Jones says. There, amongst the ruins of the centuries-old stupas and wat (a type of Buddhist and Hindu temple seen across Southeast Asia), Jones and his former enemy were led through a forgiveness ceremony. Many of the local schoolchildren and villagers attended.

It was the first real relief he’d felt since coming home from the war.

“Part of PTSD is that you don’t let things go. You mask things with drugs, alcohol, and different abuses,” Jones said. “For me, [that meeting] freed me up a lot, thinking I’m not totally responsible for the actions that were imposed on us during the war.”

In 2017, Jones returned to helping kids work through their own problems on the trail in Washington. He found himself once again working with his old friend Don Super.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

“One night, we were sitting at the campfire talking, and I told him about my adventure of going back to Vietnam and Cambodia,” Jones remembers, “and then he started telling me his story. And I was like, ‘Wow, that’s a lot to deal with… If you ever want to go back, I’ll go back with you.’”

Two years later, the pair made their first trip together to Laos. As they toured across the country, they met residents who’d been permanently disabled by unexploded ordnance in recent years. Super still speaks enough Lao “to get around” to understand their stories. They heard one from a man who approached them while sitting on a skateboard in the city of Luang Prabang, the home of the Phra Bang Buddha, the very symbol of Lao sovereignty.

Don Super chats with Phongsavath “Pong” Manithong, one of the many who have been severely injured by a blast from a mine. (Photo courtesy of Ken Hayes and the documentary film Collateral Damage)

“He had been blown up at the hips and used an old shower thong on one hand to push himself along,” Super says. “He was surprised that a foreigner spoke Lao, but when I asked what had happened, he explained that one day he was tending his rice paddy with his water buffalo when his hoe struck a mine, taking his legs and killing the buffalo. He’s been like this ever since.”

Super reached into his wallet and gave the man a $100 bill. He knew it wouldn’t change the injustice of what happened here. But every story he heard has changed him.

“There’s a healing,” he said, “that takes place every time I go back.”

This War Horse story was edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.