Pinkerton: D-Day Reminds Us How War Forged the Youthful Steel of the Greatest Generation

Of all the many commemorative speeches about D-Day, perhaps the most famous was delivered by President Ronald Reagan on June 6, 1984—his ode to “The boys of Pointe du Hoc.”

God knows, those Rangers were young. And yet, Reagan continued, they were the men who took the cliffs, the champions who freed a continent, the heroes who defeated Hitler. Intriguingly, their commander, thick in the action, Lt. Col. James E. Rudder, was just 34.

That’s a key reason why the Greatest Generation was so great. They learned early on to grapple with serious matters. Dealing with life and death, they grew up fast, and that maturity propelled them to success in later life.

The same point, about the youth of the D-Day warriors, comes across in historian Alex Kershaw’s chronicle of those who parachuted in ahead of the aerial drop to set up radio links and landing lights to guide the main force. Note the ages:

In the plane’s cockpit was lead pilot Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch. The commander of the IX Troop Carrier Command’s pathfinder unit, Crouch, 33, was considered the best in his business, having previously been the lead pathfinder pilot for the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 and of mainland Italy a few months later. To his right was copilot Captain Vito Pedone, 22. Behind them was navigator Captain William Culp, 25.

Another example: The tall man listening to then-Lt. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower on D-Day Minus One was 1st Lt. Wallace Strobel, who had no time to celebrate June 5, 1944—his 22nd birthday.

General Dwight D Eisenhower talking with American paratroopers on the evening of June 5, 1944, as they prepared for the Invasion of Normandy, in Greenham Common, Berkshire, England, on June 5, 1944. The men are part of Company E, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, at the 101st Airborne Division’s camp in Greenham Common. Photo includes Sgt Russell Wilmarth, behind Eisenhower’s chin, Lt Wallace C Strobel with a “23” tag, Ralph “Bud” Thomas, to the left of Strobel, (and probably Corporal Donald E Kruger, in front row, far right, wearing a musette bag on his chest. (Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

D-Day, Normandy, U.S. Army paratroopers just before they took off for the initial assault of D-Day. (HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Another young man about to prove himself was Capt. Dick Winters, 26, of the 101st Airborne. He would lead his Band of Brothers from the Normandy drop zone all the way to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest.

Even the top commanders who went ashore with their troops were young. Maj. Gen. Joseph Lawton Collins was 48. For another two-star, Charles H. Gerhardt, D-Day was his 49th birthday.

Yes, war is a country for young men. Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., a combat veteran of World War One, was 56 when he landed with the first wave at Utah Beach. Realizing that his troops had missed their target beach, he surveyed the unfamiliar terrain and declared, “We’ll start the war from right here.”

Ignoring enemy fire, Roosevelt directed the follow-on waves as they fought their way inland. For his exemplary courage, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. And yet it was posthumous, as he died of a heart attack in July 1944. Even if you’re not hit, combat can be lethally stressful. Younger hearts might not be braver, but they are sturdier.

The youth of military leaders is, in fact, a steady pattern across World War Two. Writing of one exemplar cut down young, the legendary journalist Ernie Pyle filed this dispatch from the Italian warfront on January 10, 1944:

In this war I have known a lot of officers who were loved and respected by the soldiers under them. But never have I crossed the trail of any man as beloved as Capt. Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas. Capt. Waskow was a company commander in the 36th Division. He had led his company since long before it left the States. He was very young, only in his middle twenties, but he carried in him a sincerity and gentleness that made people want to be guided by him.

Waskow was in fact 25 when he gave his life for his county. So, we can only speculate as to what else he might have accomplished in a longer life.

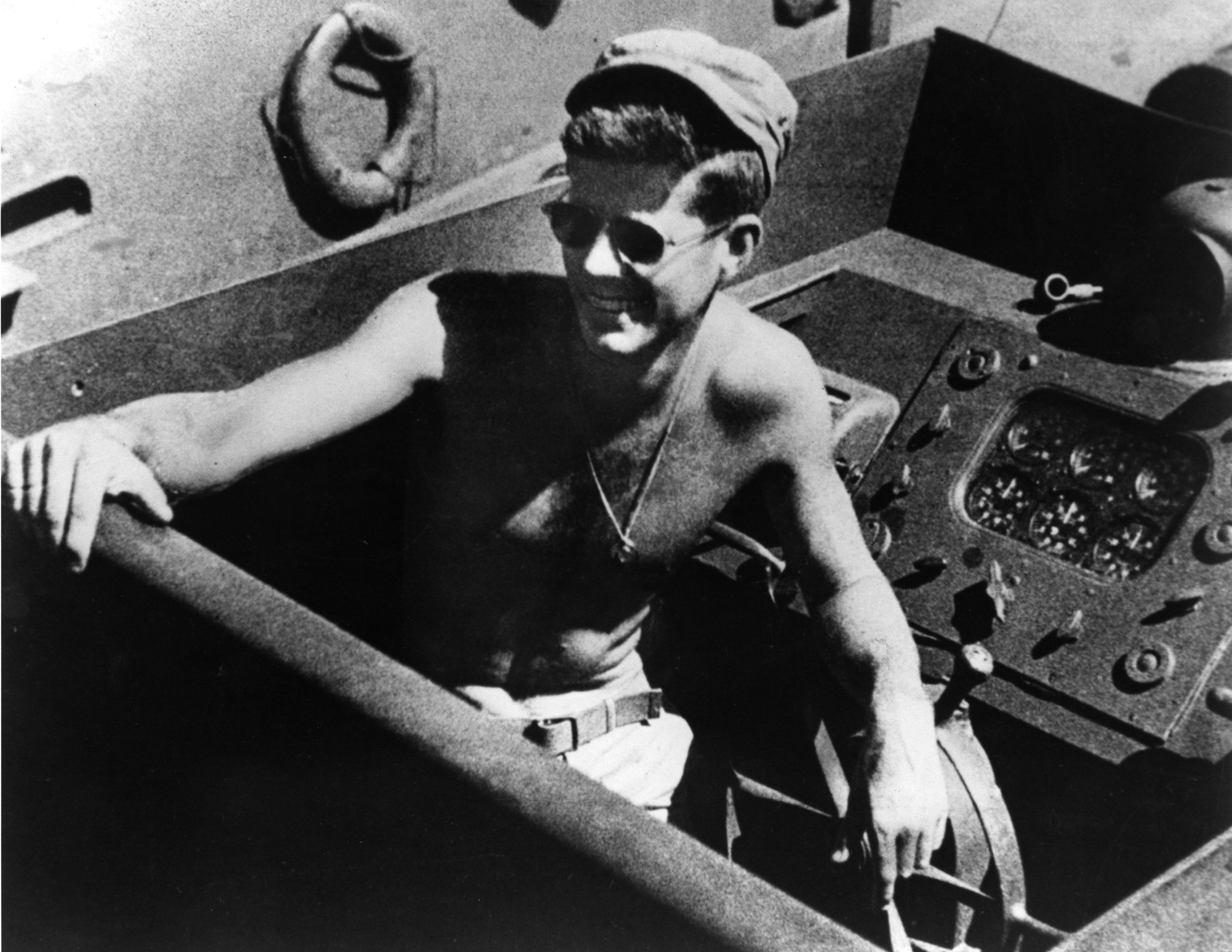

Of course, the vast majority of American GIs survived the war, and some went on to political distinction at an early age. U.S. Navy veteran Richard Nixon was 33 when he was elected to Congress in 1946, and 39 when he was elected vice president. His fellow Pacific theater veteran, John F. Kennedy, was elected to Congress at 29 and elected to the presidency at 43.

Naval Lieutenant and future President Richard Nixon serving in the Pacific during World War II. (Fotosearch/Getty Images).

Naval Lieutenant and future President John F. Kennedy on board the torpedo boat he commanded in the Pacific during World War II. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

Were these new leaders better for their war experiences? The voters certainly thought so. And indisputably, they won World War Two, and then provided the leadership that helped the U.S. prevail in the Cold War.

To be sure, war has always been the crucible in which youthful steel is forged. For further perspective, we might recall the witness of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Born in 1841, Holmes was commissioned into the U.S. Army at age 20, there to fight with 20th Massachusetts in the Civil War. Wounded three times in combat, he was mustered out in 1865 as a colonel. Much later, he was appointed to the Supreme Court, where he served for three decades.

Along the way, in a famous speech delivered to a veterans’ group on Memorial Day, 1884, he recollected the fighting, including the brave leadership of very young men:

I see another youthful lieutenant as I saw him in the Seven Days, when I looked down the line at Glendale. The officers were at the head of their companies. The advance was beginning. We caught each other’s eye and saluted. When next I looked, he was gone.

That was James J. Lowell, killed in action at 24. Then Holmes recalled Major Henry L. Abbott, dead at 22:

He entered the army at nineteen, a second lieutenant. In the Wilderness, already at the head of his regiment, he fell, using the moment that was left him of life to give all of his little fortune to his soldiers.

We’ll never what greater gifts Lowell and Abbott—and all the rest—could have given had they lived longer.

Future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. poses in his Union Army uniform during the American Civil War, circa September 1861. (Authenticated News/Getty Images)

Yet amidst the wistfulness, Holmes offered uplift to his battle-scarred fellows: “The generation that carried on the war has been set apart by its experience,” he emphasized. “Through our great good fortune, in our youth our hearts were touched with fire. It was given to us to learn at the outset that life is a profound and passionate thing.”

That was the genius of Holmes’ oration: The bloody ordeal was actually a kind of gift, the gift of dedication to a cause greater than self:

We have seen with our own eyes, beyond and above the gold fields, the snowy heights of honor, and it is for us to bear the report to those who come after us.

The Civil War veterans are all gone, of course, and yet they report to us—and inspire us—through monuments across the nation. And the vets of D-Day, and World War Two, will all be gone soon.

Yet their glorious youth, all those decades ago, lives on in memorials, such as the wondrously vivid bronze statue at Colleville-sur-Mere, overlooking the Normandy beaches. There, forever, the spirit of youth touches the heights of honor—and our hearts.

If they could do what they did when they were so young–not just fight and die as heroes, but also lead to victory as champions–then all of us, at any age, can be better, be more selfless. And if so, then the boys will not have sacrificed in vain.