The Fight After the Fight: My Dad’s War Didn’t End When He Left Vietnam

Growing up, my father had a rule: If I needed to wake him up, I should shout from the doorway. I was never to go near him when he was sleeping because he feared that he would awaken from a flashback dream and accidentally hurt me.

I was just 6 years old, but I had begun to realize that war doesn’t stop when you leave the battlefield.

I used to pester my dad to tell me about his experiences as a Marine in Vietnam, but I can count on one hand the stories he shared. The closest I ever came to learning about his battlefield experiences was when we watched “Full Metal Jacket,” and he said it was more like a documentary to him. When I went to Washington, D.C., with my eighth-grade class, my dad gave me a list of names that he wanted me to photograph on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. I watched him tear up in the theater when we saw “We Were Soldiers,” but even then, he never told me why.

Although he didn’t reveal the specific stories behind his memories, I saw the other effects from his service.

Once, I took him out to dinner, and he mentioned that he had just gotten his new dentures from the VA. I dryly commented that it must be nice to get free dental care. He looked me in the eyes and said, “Andrea, you don’t want to go through what I did to get free dental care.”

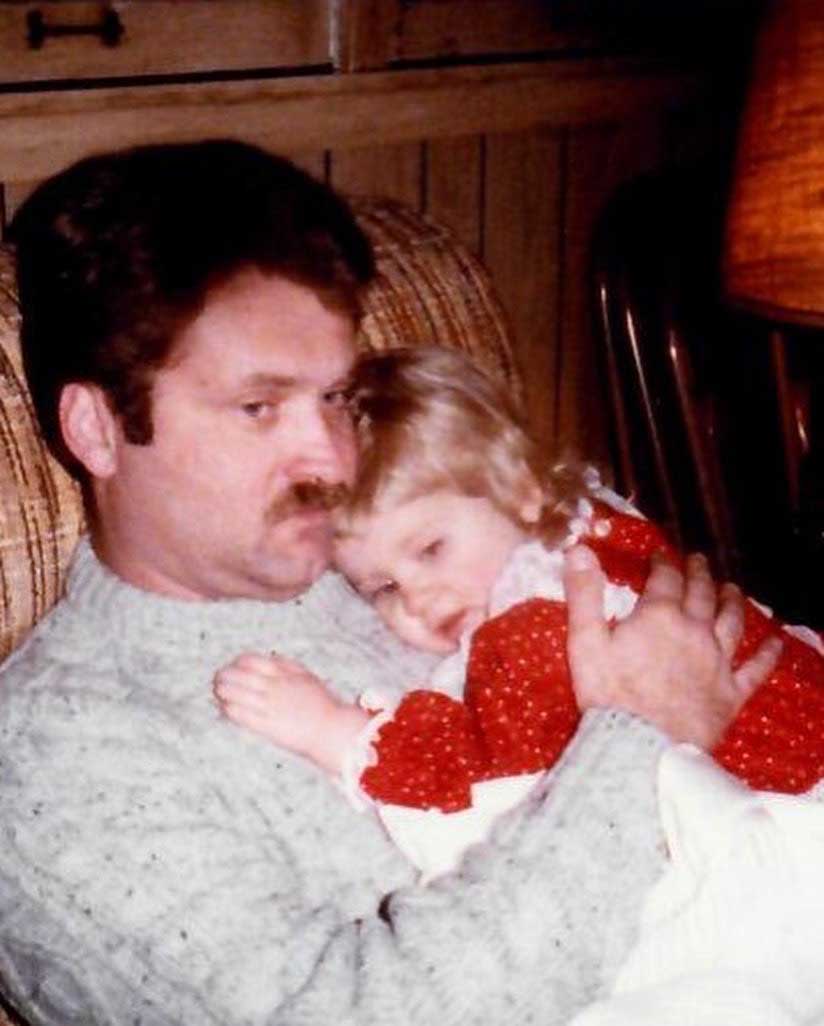

The writer, at age 2, with her father, Roger Madden. When she was sad, she only wanted her father. (Photo courtesy of Andrea Madden)

He was right. The VA considered him to be 70% disabled because of his PTSD, and he lived with prostate cancer due to his Agent Orange exposure. He wore a catheter for almost two years while working full-time and taking public transportation.

But telling the story of a veteran is not just about the hardships. It’s about life after the war. It’s about the fight that comes after the fight, and the joys that come after as well.

My dad was a fighter and the toughest human being I have ever known. Yet he was also the one who took me and my best friend Stacey trick-or-treating every year, complete with a final stop at McDonald’s for ice cream. He was the one who played Nintendo with me and bought me my first CD player. When I was 16 and worked at JCPenney, my dad often visited me at work just so we could eat at the food court during my breaks.

He rescued pit bulls, especially those taken from fighting rings. He thought they deserved a second chance just like he did.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

I adored him. And in many ways, I turned out just like him. He learned everything he could about topics that interested him, and he loved sharing that knowledge with others. As I got older, we would constantly debate politics and social issues. And even though we were on opposite ends of the spectrum, I believe that he was secretly impressed with how strong I was in my beliefs and how stubbornly I stood my ground—just like him.

Roger Madden, on his way to Vietnam. (Photo courtesy of Andrea Madden)

And just like my father, I also struggled with alcoholism. He got sober in 1976, and maintained his sobriety even after my brother passed away at the age of 47. When I got sober in 2021, I remember hearing the pride in my dad’s voice that I was finally admitting to something that he had always known.

He regularly saw a therapist and advocated for mental health care. When I moved from Chicago to western Massachusetts to enter a residential treatment center for mental illness when I was 32, he was my top supporter. His biggest concern was that I would become a Patriots fan, which I assured him would never happen because I was raised to cheer for the Vikings and the White Sox.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

I always thought that a veteran’s strength was measured in what they did on the battlefield, and I spent years wishing my dad would tell me about his experiences. However, those were not my stories to know. Those were his stories to share or keep as he saw fit. He chose to leave his stories of Vietnam on the battlefield and look forward to his life after the war.

He had to find a way to create a life out of his experiences, and I’m here to say that it was a good life. My dad knew how to be tough, but he also knew how to love and laugh and enjoy a good meal. It wasn’t always easy, but I didn’t see the pain or the struggle. I saw my dad.

This War Horse reflection was edited by Kim Vo, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mollie Turnbull. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.