The Story Behind Operation Pineapple Express, a Daring Rescue Effort in Afghanistan

The abrupt departure of the final American troops from Afghanistan last year after two decades of war plunged Kabul into anguished chaos. Watching coverage of the withdrawal at home in Tampa, Florida, Scott Mann sank into furious disbelief.

The former Green Beret had served multiple tours in the country, training Afghan special forces commandos and later working to extend the reach of the democratic government through village stability operations in rural areas. He knew the Taliban’s return to power would unwind the advances of the previous 20 years—and expose the commandos and their families to brutal revenge.

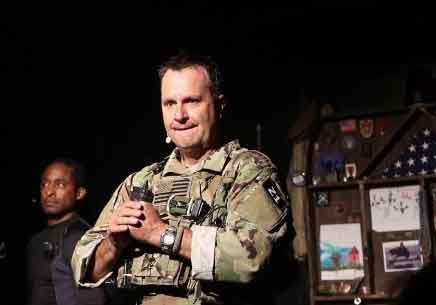

Retired Lt. Col. Scott Mann tells his story in Last Out: Elegy of a Green Beret in 2019. Photo courtesy of Scott Mann.

Mann had hung up his Army uniform in 2012 after 22 years of service, disillusioned by the war’s direction and what he regarded as the career-first mindset of U.S. military commanders. But as his phone filled with text messages from Afghan commandos desperate to escape, and with American forces lacking a cohesive evacuation plan, the retired lieutenant colonel found himself pulled into one last mission from 8,000 miles away.

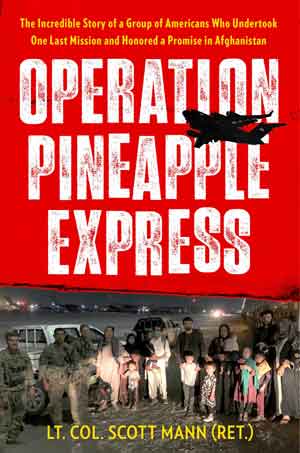

Operation Pineapple Express, which came out from Simon & Schuster in August, offers Mann’s account of enlisting a volunteer team of fellow veterans to build a digital underground railroad for Afghans fleeing the Taliban. Connected by a Signal chat room from points around the world, the group’s members worked with U.S. troops on the ground at Kabul’s airport to guide more than 750 “passengers” out of the country.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Mann’s pride in the work of Task Force Pineapple—the name derived from the code word “pineapple” that a commando used to gain entry to the airport—contrasts with his sharp criticism of American military leaders. He spoke from his home in Tampa about why he considers the U.S. withdrawal a mistake, the sense of duty that drove U.S. veterans to help Afghans escape, and the lasting toll of the longest war in U.S. history.

Let’s go back to before the evacuation. How did you view the decision to pull out all U.S. forces?

We went into Afghanistan on the heels of the most catastrophic terrorist attack on our soil in history. It’s not a stretch to say that the absence of a solid ground intelligence network—and reliable local partners to serve as an antibody to violent extremism—vastly contributed to that attack. For 20 years, our military fought to put in place both an intelligence network and a reliable partnership with the Afghan security forces that could serve as an antibody to al-Qaida and the Islamic State group.

Former Green Beret and Army Lt. Col. Scott Mann wrote a book about the American withdrawal from Afghanistan and the attempt to help Afghans flee the country.

The partner that did the bulk of the fighting was the Afghan special operations forces. You’re talking about 25,000, 30,000 special operators. I believe that our senior administration officials—starting with the president—should have asked themselves, “What do we need to do to ensure that they have what they need to hold the country?”

So the U.S. military should have kept troops on the ground?

We always said, with village stability operations and building capacity with the commandos, you’re talking about decades, not years. Green Berets typically think about it that way: It’s a long game; it’s all instruments of power. What could that have looked like? A small U.S. force that stayed focused on counterterrorism and capacity-building with the Afghan special forces units that were keeping the Taliban at bay.

Would the Taliban have been able to make moves in the outlying provinces? Yes, and maybe there would’ve had to have been an arranged peacekeeping deal. But I do believe we could’ve maintained a presence in that country that was acceptable, particularly if we had continued to work with NATO. We could have continued to help hold space so that the security forces and the relative democracy that was in place could continue to grow. Instead, we literally walked away, knowing how it was going to end.

As Kabul fell into disarray and you began hearing from Afghan commandos you knew, what was your reaction?

At first, I was wrestling with, “I cannot believe nobody else is doing anything,” and, “Man, I really don’t want to get involved with this again.” But at some point, it was just like, “Screw it. We gotta do something.” Then when I started calling some of the others who became part of Pineapple, I saw that they were in the same place. They were facing the same fears and frustrations and guilt, and they were realizing the same thing: We can at least do something.

Nezamuddin Nezami, an Afghan commando, and Scott Mann pose after a combat patrol in southern Afghanistan in 2010. Mann, a retired Army lieutenant colonel, helped Nezami and his family escape Kabul last year after U.S. troops withdrew from the country. Photo courtesy of Scott Mann.

You write that U.S. veterans, beyond a sense of obligation to Afghan soldiers, acted out of despair over what they saw as America abandoning its principles.

Here’s the thing: These veterans know something that the politicians, the diplomats, and the careerist senior military officers don’t know. It is that there is a requirement in our line of work that “I have your back” means something. They know that our failure to honor that promise is way bigger than the moral issue.

One of the veterans in our group said, “Not only did the evacuation wind up on our shoulders, but we find ourselves trying to restore the honor of the United States.” My goodness. What kind of massive task is that? The redistribution of responsibility from our institutional leaders onto the shoulders of our veterans is disgusting.

What have been the effects on veterans who chose to carry that burden?

The people who bore the bulk of the cost of our withdrawal were the Afghans and the U.S. troops that went over there. But there was—and is—an enormous cost to these volunteers in groups like Pineapple: high stress levels, lack of sleep, financial struggles, marital strain, retriggered trauma.

There are groups that I’m still working with through the Moral Compass Federation—18 organizations that banded together whose volunteers are still trying to get Afghans out. These are people who don’t know how to say no. So how does this end for them? The level of moral injury they’ve incurred is staggering.

The impact of the withdrawal on the veterans’ community—as with the war itself—seems all but invisible to most Americans. Do you worry that the country has simply moved on?

A group of Afghans wait at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul during the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan last year. Task Force Pineapple aided their escape from the country. Photo courtesy of Scott Mann.

That’s really the reason I wrote the book: I intend to get as loud as I need to get because this isn’t over. I believe we’re on the front end of a catastrophic fallout with mental health with our veterans and military families. You have 73% of veterans saying they feel betrayed [by the withdrawal]; 67% feel humiliated. So what are we going to be looking at in terms of depression, substance abuse, homelessness? Their sense of betrayal and abandonment—nobody is talking about that. And nobody is talking about the impact in terms of [military] recruiting and retention. You have senior leaders scratching their heads, saying, “Wow, I wonder why our numbers are so low.”

Scott Mann, a former Green Beret who trained Afghan special forces commandos during multiple tours in Afghanistan, stands in a valley in Oruzgan province in 2004. Photo courtesy of Scott Mann.

You call out—by name—those who you think failed to aid Afghan commandos as the Taliban reclaimed power, including two Army generals who are now retired: Richard Clarke, the former head of U.S. Special Operations Command; and Austin Miller, the last NATO commander in Afghanistan. What’s your intent?

It’s about accountability. Senior leadership could have influenced what happened on the ground and helped the commandos to at least develop an underground plan for guerilla warfare and get their families to safety. But there was no effort—at all—by the leaders of the Special Forces and Special Operations Forces. The commandos were abandoned.

What do you want U.S. military officials to learn from the withdrawal and its aftermath?

My dad is my hero, and he was the one who said to me early on (about helping Afghans escape), “Scotty, you guys are honoring a promise, and I’m telling you right now, you don’t want to be on the wrong side of this.”

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

That’s a conversation we need to have with our senior leaders. Careerism is one of the greatest national security risks we face in our military. It has gotten so bad that things like basic humanity and honoring a promise—we don’t stand up for those things anymore at the highest levels, and that to me is as dangerous as ISIS. We need to get rid of those people—fire or demote them—and have people step into those positions who are willing to lead the right way.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This War Horse feature was reported by Martin Kuz, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Jasper Lo, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

Comments are closed.