Black Veterans Have Always Fought Two Wars, Battling the Enemy Abroad and Prejudice at Home

In the summer of 1946, George Dorsey, a World War II veteran who had served tours in North Africa and the Pacific theater, was easing back into post-war life after five years in the Army. He was working as a sharecropper in Walton County, Georgia, after returning home, and living with his wife, Mae.

On July 25, just 10 months after Dorsey came home, a mob of white men swarmed a car that contained Dorsey and Mae, as well as Dorsey’s sister and brother-in-law. Enraged by a report that Dorsey’s brother-in-law, Roger Malcom, had stabbed a white man, the mob eventually pulled both couples from the car, beat them, and shot them more than 60 times. Although people witnessed the lynching, and although the men in the mob didn’t hide their faces, the police made no arrests. The crime is still officially unsolved today.

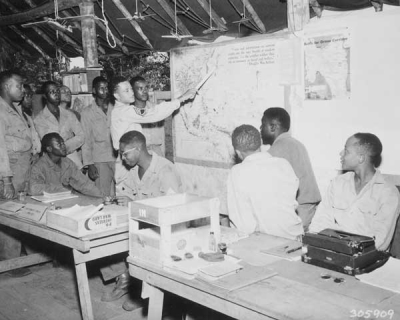

Black soldiers in the 477th Antiaircraft Artillery, Air Warning Battalion, study maps in the operations section at Oro Bay, New Guinea, on Nov. 15, 1944. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

In the years following World War II, in which well over a million Black Americans joined the fight against fascists, troops returned home to a nation that, in many ways, was still decidedly antidemocratic. Jim Crow laws and discrimination, both sanctioned and unofficial, shaped the reality of post-war life for many Black veterans. Just as had happened upon their return home from World War I, American servicemen and sometimes women came back from World War II to bigotry, exclusion, and overt racial violence—precisely because they had served their country.

“They were a threat because they carried themselves with pride,” says Matthew Delmont, a history professor at Dartmouth who has written about Black Americans in World War II. “This is true during the war and after the war—just the sight of a Black person in a military uniform was upsetting to a lot of white Americans.”

Although Black Americans have fought in every conflict since the Revolutionary War, the breadth and dedication of their service, and their distinct experiences in uniform and upon returning home, are often omitted from or minimized in historical narratives of military service—part of a legacy of discrimination that continues today.

“We have to start with the fact that when America thinks about a veteran, they often think about a white man,” says Richard Brookshire, the co-founder of the Black Veterans Project, which works to elevate the stories of Black veterans and servicemembers. “There is an erasure, an erasure to the historical harms and the present-day harms that continue for Black people who serve.”

Hosea Williams was awarded a Purple Heart after facing the Germans in World War II. When he returned home, he helped lead civil rights protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Here, protesters face Alabama State Troopers. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Historians regard the lynching of George Dorsey, his wife, and Roger and Dorothy Malcom—often known as the Moore’s Ford lynchings for the place where they died—as the last mass lynching in American history. The Moore’s Ford lynchings were not the last lynchings in the country, nor were they the last lynchings of a veteran. But their extraordinary brutality, the lack of accountability even after multiple investigations, and that they involved a veteran so recently returned from war ignited a national backlash against the racial violence so many Black Americans faced. This ultimately helped to pave the way to the civil rights movement—a movement that Black veterans, shaped by their experiences in uniform, pushed forward.

“Black Americans have served in every military conflict the United States has ever been a part of, going back to the American Revolution, Civil War, World War I, World War II,” Delmont says. “But that service has always meant a different thing than it’s meant to most white servicemembers.

“Theirs was a critical form of patriotism. They wanted to really fight to make America a country that was worth fighting for.”

We Knew That Not to Be True

In his 1917 speech to Congress asking the United States to enter World War I, President Woodrow Wilson argued that “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

“We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind,” he declared. “We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.”

But in war—as on the homefront, where Wilson’s administration aggressively pursued segregation in the federal government, as well as the removal of Black government officials—the rights of mankind were not equally extended. More than 350,000 Black sailors and soldiers signed up or were drafted to serve in World War I. But they faced discrimination in the ranks: pushed into jobs white soldiers didn’t want and issued inferior gear and equipment. White service members sometimes refused to salute Black officers, who were often barred from officers’ clubs and dining halls, and at times Black soldiers had to eat and sleep outside. Some Black soldiers were even issued decades-old Civil War uniforms.

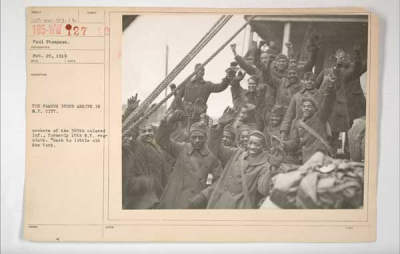

The 369th Infantry Regiment returns to New York after serving in World War I. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Still, within the Black community, many saw benefit in joining. Intellectual leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois initially encouraged Black citizens to join the war effort, both out of a sense of patriotism and in hopes that proving patriotism would open doors to greater opportunity.

“He encouraged Black people to serve because it would be a pathway to equal citizenship,” Brookshire says. “When folks got back from World War I, we knew that not to be true.”

In the summer of 1919, following the end of the war the previous fall, the country was swept up in a spasm of horrific nation-wide racial violence, which came to be known as the Red Summer. Race riots broke out in Chicago, Washington, and many other cities. White mobs lynched dozens of Black Americans. At the end of September, in an anti-Black massacre in rural Arkansas, where Black sharecroppers had attempted to negotiate pay and cotton prices, roaming mobs of armed white men killed more than 100 Black citizens.

Returning veterans were not immune from this violence. Rather, mobs often targeted Black soldiers and sailors who had served in World War I because they had served.

In 1917, Sen. James Vardaman of Mississippi warned against allowing Black Americans to join the military, arguing that it would inflame the fight for equal rights.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

“[I]nflate his untutored soul with military airs,” he said in a speech on the Senate floor, adding, “It is but a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected.”

It was a sentiment that echoed in communities across the south, where many white citizens felt compelled to prove those rights would not be respected. In Kentucky, just a month after the end of the war, a recently discharged Army private named Charles Lewis was arrested while wearing his uniform after a white sheriff accused him, without evidence, of robbery. Upon hearing of his arrest, a crowd of nearly 100 men broke into the jail where Lewis was held and murdered him by hanging him from a tree.

Likewise, in Texas, another recently returned veteran, Ely Green, was beaten by four white police officers for wearing his uniform in public. During the summer of 1919, Lucius McCarty, a Black veteran in Louisiana, was shot more than 1,000 times after he was accused of trying to assault a white woman. In Arkansas, a Black veteran named Frank Livingston was burned alive after a white mob tortured him into confessing to murdering a white couple.

Second Lt. Freda le Beau serves Maj. Charity Adams a soda at the opening of a new snack bar for the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion in Rouen, France. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Active duty sailors and soldiers were also targeted. In 1917, the Black 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment was sent to Houston, where police officers and local citizens harassed them. The abuse eventually led to an armed riot in which four Black soldiers and 16 white civilians died. Nineteen Black soldiers were later sentenced to death and executed.

In May 1919, hundreds of white Navy sailors stormed into a hotel in New London, Connecticut, where Black sailors from the nearby naval base often congregated, pulling their fellow sailors outside and beating them.

“What does that say to African Americans, let alone any other group, that on one hand, you desperately need us—you tell us it’s our responsibility, that we are American citizens. We need to step up to the plate,” says Charissa Threat, a history professor at Chapman University who writes about gender and race in veterans’ history. “We want to step up to the plate. But we are met with both discrimination while serving, violence while serving, and certainly [when] coming home.”

They Will Not Send Their Sons to War Again

In the years between World War I and World War II, the organizing power of Black activists expanded as anger grew over persistent inequality and the waves of racial violence. Membership in the NAACP, founded in 1909, swelled from 9,000 in 1917 to more than 90,000 just two years later. The organization and Black activists pursued legal cases challenging discrimination and segregation, and worked to document the extent of the violence Black Americans faced. Professional organizations for Black workers excluded from white organizations also grew and fought for more equal working conditions.

As World War II loomed, so did the same questions about patriotism and equality Black soldiers and sailors in World War I faced.

“You have veterans who have served in World War I, who have done a lot of work during the 1920s and 1930s, and who are very vocal that they will not go or send their sons or their grandsons, in some cases, to war again, if something doesn’t change,” Threat says.

Black leaders pushed for greater equality and better treatment on the homefront and in the military. Walter White, the executive secretary of the NAACP, and A. Philip Randolph, the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, pressured the Roosevelt administration to end segregation and discrimination in the military branches—Black citizens were not allowed to join the Marine Corps until 1941—and the defense industry. Activist organizations sought, again, to connect a willingness to fight with the need for equal rights.

Members of the 369th Infantry Regiment return home on the U.S.S. France. The men “covered themselves with glory,” according to the original cutline. But upon their return home, they faced discrimination, abuse, and even death. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

“They were not just talking about access to military service or improvements for Black servicemembers,” Threat says. “They were also talking about—how do we use military service to then leverage political change or social change as well?”

Ultimately around 1.2 million Black soldiers, sailors, and airmen served in World War II. While some stories, like that of the Tuskegee Airmen, the all-Black Army Air Corps squadron, are well-known military lore, African Americans’ service during the war—much of which was in service, logistical, and construction positions—has largely been sidelined.

But the positions in which many African Americans served were critical to the Allied victory, Delmont says.

“If you think of something like the Red Ball Express truck drivers, that were primarily Black truck drivers, they fueled the logistical effort in the weeks and months after D-Day,” Delmont says. “They moved 400,000 tons of ammunition, food, and fuel that really made it possible for America’s troops to push across France and eventually into Germany.”

“Those aren’t usually the stories we tell about World War II,” he says. “They’re not glamorous or not sexy stories, but it’s the reality of how a war was won at that scale.”

The Military Chose to Default to Local Prejudices

In January 1942, a Black veteran named James Thompson wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most respected and widely read Black publications in the country.

“Like all true Americans, my greatest desire at this time, this crucial point of our history, is a desire for a complete victory over the forces of evil, which threaten our existence today,” he wrote of the war.

But he suggested that the fight against tyranny abroad paralleled the fight for civil rights in the United States, arguing for a two-pronged campaign. The effort, known as the Double V campaign, quickly took hold in African American communities, as activists championed victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home.

“They saw their military service as part of a larger battle,” Delmont says. “They absolutely wanted to defeat the Nazis and Axis forces. But they knew that wasn’t enough. They knew that they also had to defeat racism and white supremacy in the United States.”

The movement built on interwar organizing efforts, but Black service members continued experiencing extraordinary racism. Many of the military’s bases were in the South, where Jim Crow was still the law of the land. And Black soldiers from Northern states often encountered the legal racism of the South firsthand at the same moment they had stepped up to serve their country.

Pvt. William A. Reynolds, an ambulance driver, exhibits a .50-caliber machine-gun bullet that lodged above the windshield of his vehicle when he was strafed by a German plane while driving at the front in France in 1944. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

“This was federal property—whether these bases were in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Massachusetts, wherever they were—this was federal property,” Delmont says. “And yet, the military chose to default to whatever the local situation was, the local prejudices were, with regards to race.”

At the same time, Black GIs sent to other Allied countries found cultures unaccustomed to the same levels of racial prejudice as in the Southern U.S.—a fact that sometimes infuriated white commanders.

“You have military officers often from the South, who have every expectation that they could transport Jim Crow to England or to Australia, and that it would be accepted by the local communities,” Threat says. “Sometimes it was, but oftentimes it was not. And then you have Black service members who are in that space, who are allowed to do things or are welcomed in different ways. And so that is also creating tension between white service members and Black.”

The same tension greeted service members upon their return home, just as it had after World War I. In 1946, a Black veteran named James Stephenson, who had worn his Navy uniform with his mother to a store at home in Tennessee, pushed a store worker after the worker slapped his mother. In the aftermath, an infuriated white mob attacked local Black businesses. Stephenson and his mother managed to escape, but more than 100 Black people were arrested.

Hosea Williams, who had been captured by the German army and was later awarded a Purple Heart for an injury gained in Europe, was on his way home to Georgia when he tried to drink from a white-only water fountain. He was attacked by a mob that beat him so severely they assumed he was dead and called a Black funeral home to come to pick up his body.

“The war had just ended, and I was still in my uniform, for God’s sake!” he later said. “But on my way home, to the brink of death, they beat me like a common dog. The very same people whose freedoms and liberties I had fought and suffered to secure in the horrors of war … they beat me like a dog.”

I Was in Two Wars

Nineteen years later, in 1965, Williams helped to lead nearly 600 civil rights protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. State troopers armed with tear gas and nightsticks, along with private citizens, deputized just that morning, waited on the other side. Williams attempted to speak with the commander in charge of the Alabama state troopers, but the commander refused to speak with him, and police began to brutally attack the protestors, beating them with billy clubs and whips, in a day that would come to be known as Bloody Sunday.

“I had fought in World War II, and I once was captured by the German army, and I want to tell you the Germans never were as inhumane as the state troopers of Alabama,” Williams later said.

Williams was far from the only civil rights leader who had served in the military and been shaped by his experiences. Medgar Evers was a World War II Army veteran. James Meredith, the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, had served in the Air Force. Ralph Abernathy, who helped create the Montgomery Bus Boycott, had been a platoon sergeant in the Army. Jackie Robinson, before his baseball career, was court-martialed during his Army days for refusing to sit in the back of a bus.

A kitchen was set up along the beach at Massacre Bay, Attu, Aleutian Islands, for a battalion as they unloaded the boats. Here, the men enjoy a hot meal on May 20, 1943. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

“It was a small victory,” Robinson later wrote of his offense being acquitted, “for I had learned that I was in two wars, one against the foreign enemy, the other against prejudice at home.”

The civil rights movement ushered in a fairer world for Black Americans—but the fight for equal rights continues and the legacy of discrimination endured by Black soldiers still echoes today. Widespread disparities in accessing GI benefits, like housing loans and education stipends, meant that veterans of color were regularly denied the benefits that many white veterans relied on to establish their post-World War II lives. Veterans Affairs itself encouraged Black veterans to apply for vocational assistance, rather than money for higher education. Banks regularly denied VA loans for Black veterans. This systematic discrimination still bears consequences for the children and grandchildren of those veterans today.

“The results of service don’t always lead to increased or full benefit rights,” Threat says.

Even today, internal VA documents obtained by the Black Veterans Project show that Black veterans are less likely to be approved for benefits for post-traumatic stress, according to an ongoing lawsuit against VA.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

“There’s been such an emphasis on the physical violence,” Brookshire says. “But we have a responsibility as a society to hold equal weight to the economic violence, and spell it out.

“Because it has a real tangible impact—a tangible impact on the life outcomes of people, the health outcomes of people, the possibility [for] their children.”

This War Horse feature was reported by Sonner Kehrt, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

Comments are closed.