Breitbart Business Digest: Inflation Threatens to Disrupt Rate Cut Plans

A Weft of Warning for Wall Street

In the grand tapestry of economic indicators, the threads of the producer price index (PPI) are all too often overlooked. This month, however, the warp and weft of producer prices came in bold hues depicting with stark clarity a portrait of inflation rising like a phoenix from the ashes.

The index for final demand producer prices rose 0.3 percent, three times the gain forecast by Wall Street’s soothsayers. The core index, which excludes food and energy prices, rose 0.5 percent. Core-core, which also cuts out trade services, rose by 0.6 percent, the largest monthly increase since January of last year.

The report illustrated the shift in inflationary pressures from goods to services. Goods prices fell 0.2 percent compared with the prior month but services prices surged 0.6 percent.

This suggests that we’re in for a prolonged period of high inflation because services inflation is stickier than goods inflation. When prices rise for goods, manufacturers and farmers ramp up production to meet the growing demand. When prices rise for services, it is harder to conjure forth more people to meet demand. Despite Elon Musks’s best efforts at producing Cylons, we cannot yet manufacture workers for most services jobs.

What’s more, there are troubling signs that goods disinflation could be over. Core goods prices, excluding food and energy, rose 0.3 percent, an acceleration after three months of mild 0.1 percent increases.

Peering Deeper into the Economic Fabric

If we peer deeper into the embroidery of the producer price index, we can see more inflation threading through the economic tapestry. The headline numbers for the producer price index report prices of goods and services sold for “final demand.” These are products sold to customers who are government buyers, household buyers, businesses buying capital goods, and foreign buyers. What are sometimes called end-users.

The report also includes indexes covering intermediate demand prices. These are measures of prices of goods and services—excluding capital goods—sold to businesses that then are used to produce goods and services for final demand. In other words, these are what businesses pay for materials, components, and services that go into the products sold to the households, government buyers, and global customers.

While the top index for intermediate demand goods prices declined a bit in January, this was entirely driven by a steep drop in energy prices and a smaller drop in intermediate food and feed prices. Once we strip these out, core processed goods prices for intermediate demand rose 0.3 percent. This was the second month in a row of rising core intermediate demand prices, following two months of smaller declines.

That’s a strong indication that there is more inflation in goods being knitted into the economy further back in the supply chain. As a result, it is likely that we’re nearing an end to the disinflation in goods that has held down overall inflation even while services prices have climbed. We may actually see a reversal, with prices of goods climbing again.

The price index for intermediate services rose 0.5 percent, the third consecutive month of increasing prices and an acceleration from the December pace. The rise was broad, stitching through non-residential rents and legal services to the wholesaling of metals and chemicals. Transportation services prices declined sharply, but this was more than offset by increases elsewhere.

The producer price index report makes it even harder to dismiss the consumer price index or the import prices reports delivered by the Department of Labor this week. Each is a thread wound around the other, contributing to its effect and testifying to the persistent inflationary undercurrents.

The Looming Shadow of PCE Inflation

We’ll have to wait until later this month to see the fourth major yarn of inflation, the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index. This is particularly important because the Federal Reserve uses it as the basis for its two percent inflation target and the forecasts included in the summary of economic projections.

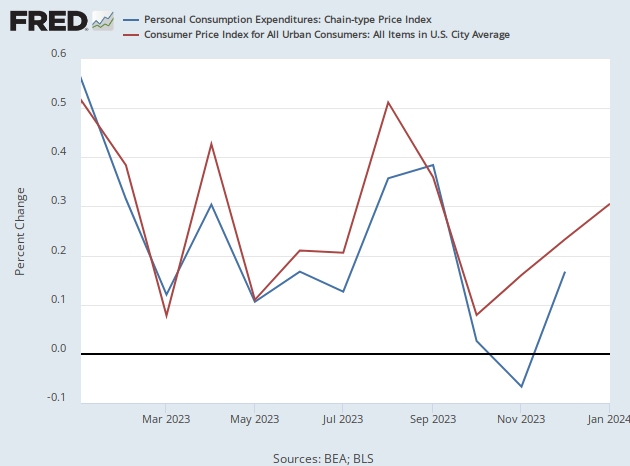

The PCE price index has been running lower than the CPI for the past few months. Some analysts who have become overly attached to their dovish narratives have used this as a way of coping with rising inflation data, pointing to PCE’s lower print as a reason why the Fed might still cut rates in the first half of this year.

That’s always been problematic because PCE inflation does not consistently run below CPI inflation. Over time, they more or less keep up with each other. The real difference is that CPI tends to crest higher and ebb lower than PCE. The rest of the time, they tend to track each other pretty well. So, if you notice that PCE is lagging CPI, you should not assume that PCE will keep lagging.

The January PCE data, which will be released at the end of February, is likely to show PCE catching up. The parts of the producer price index that are harbingers for the PCE index foretell a rise. The only question is how much. Bank of America‘s analysts thinks core PCE could come in at 0.4 percent, writing that “it appears that the wedge between core PCE and core CPI is likely to be small this month.”

The Federal Reserve has lately been signaling a cautious approach to interest rates. After the recent uptrend in inflation, it looks increasingly likely that the Fed will hold off on interest rate cuts until at least June or July—and perhaps until after November’s presidential election, if it cuts at all. This would prove extremely frustrating to the partisans of rate cuts on Wall Street and in the Democratic wing of the U.S. Senate, but it would underscore the Fed’s commitment to stable prices and preserving its independence.

Speaking of Wall Street, the collective breath of anticipation of cuts held by its denizens could well turn into a collective gasp. The overwhelming consensus—as evidenced by a Bank of America fund managers survey where 90 percent anticipate rate cuts this year—stands on increasingly precarious ground. The economy’s stubborn inflationary signals suggest a scenario where the Fed might eschew rate cuts altogether, a prospect that could send ripples of disruption through financial markets.

The disinflationary forces that convinced so many that we were marching into a period of easing have receded, at least for now, leaving in their wake an economy still grappling with inflationary pressures. When Wall Street will recognize the pattern on the wall is still an open question.

Comments are closed.