I Learned That Loss Could Bridge the Divide That Separates Us

There is no doubt in my mind that military pilots have egos stretching to the stratosphere. I found out early in my military career that fighter pilots, as a group, are a bunch of assholes. I learned to tolerate most of them, but none considered me a buddy, and I didn’t consider any of them one either. Nonaviators knew flyboys depended on nonflyers to support them, not associate with them.

Then, on a hot, humid day at Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base in 1966, I learned that loss could bridge the divide that separates us.

Fifty-seven years later, I’m still haunted by what happened that day.

Terry Arnold as a first lieutenant at Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. Photo courtesy of the author.

But my story begins four years earlier, in 1962. After graduating from college, I knew I had a critical choice to make, one that would impact my entire life—join the military or wait for my local draft board to send me the infamous “greetings letter.”

I chose to volunteer. I wanted to be a fighter pilot. But I didn’t score high enough on my exams. (I couldn’t grasp how to turn right when I was upside-down!)

Undaunted by this failure, I applied for Air Force officer training. Since I had a college degree in broadcasting, I became an information officer. We were the ones who had to deal with the news media (local, regional, national, and international), inform the troops of the latest Air Force policies, and deal with communities. And information officers did just about everything else that nobody on the commander’s staff wanted to do. We were the public relations warriors constantly portrayed in war movies as bumbling idiots.

In February 1963, I was assigned to the fledgling 388th Tactical Fighter Wing at McConnell Air Force Base, Kansas, a place full of obnoxious pilots. The 388th was a new unit flying F-100 Super Sabers but transitioned to F-105 Thunderchiefs, which soon became the fighter-bomber of choice in conducting the air war to North Vietnam.

I received a new assignment to another F-105 unit at Takhli Royal Thai Air Base in late 1965 and then quickly transferred to Korat, which had no information officer. It was great—since the F-105 family was small, I knew many of the people I had served with in Kansas.

The old Air Force motto is to “fly and fight.” In my case, it was to “fly and write.” The majority of Air Force officers didn’t fly but supported those who did in various ways: Personnel handled records, civil engineers kept the base functioning. There were maintenance specialists, chaplains, doctors, and lawyers.

While pilots thought they were more important than the rest of us, their job—air superiority and ground attacks—was only possible with us. And they knew it. I was a “grunt,” a noncombatant, not one of the elites. I was just a “wannabe.”

Korat-based F-105s are prepared for a mission to North Vietnam.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Until a phone call changed everything.

As I sat in the comfort of my air-conditioned office across the compound from the squadron operations centers, my feelings for pilots were about to change. So was my life.

My phone rang, and I quickly answered, holding the extension away from my ear.

“Get down to the 421st ASAP,” the caller bellowed with self-righteous authority. “We’ve got a 100-mission guy on his way home. Grab your camera and bring lots of film.”

“Yes sir,” I said and hung up the phone.

I had long known that pilots had an insatiable appetite for pictures of themselves sharing glory with their flying buddies. I was a crucial part of the egotistical mysticism ingrained in all fighter pilots, since I had the only official camera on base and I was the only one authorized to use it.

Award-Winning Journalism in Your Inbox

Retrieving my trusty government-issued Kodak 35mm camera from its cabinet, I loaded it with black and white Tri-X film—no color for these guys. I must admit that I smiled as I did this because it gave me a good feeling that a pilot would soon be safely home. It had been a while since anyone had joined the 100-mission club, what we called a pilot who completed 100 missions and had therefore served his wartime duty. Often, F-105 pilots didn’t make the magic number to qualify. They were either dead or residents of the Hanoi Hilton.

As I crossed the compound to the squadron’s operations center, I could hear the jubilance spilling from the party that had started without me. Green flight suits packed the smoke-filled operations room. I squeezed through the crowd and found my contact, who was also a first lieutenant. He told me that the celebrant would land shortly.

His name was Robert Raymond Dyczkowski. Fittingly, his squadron mates called him “Diz.” I could only imagine what was going through Diz’s mind earlier that morning. He was undoubtedly feeling exuberant but also perhaps more tense than usual as tomorrow’s scheduled mission neared. Today’s sortie would be Diz’s 99th, leaving him one more to go.

In war, situations can change in a flash.

Diz’s next-to-last mission that day was routine—armed reconnaissance seeking targets of opportunity to hammer in North Vietnam’s far southern regions. Once a pilot like Dyczkowski was near the end of his 100-mission tour, commanders ensured that they flew only to “softer” targets in the southern part of North Vietnam. No Thud Ridge targets for these guys—a ridge that got its name because so many Thunderchiefs had crashed there. In fact, the nickname for the F-105 was “Thud” presumably because, as the pilots with their sick humor liked to say, that was the sound it made when it hit the ground.

Col. Robert Raymond Dyczkowski was a member of the 421st Tactical Fighter Squadron. On April 23, 1966, he piloted an F-10D Thunderchief on a bombing mission in North Vietnam. He was never seen again. In 2000, modern forensic techniques identified his remains, which had been repatriated in 1977. Photo courtesy of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

As I sat among the fighter jocks, I imagined Diz earlier that morning taxiing his mighty steed to the end of the runway where crews would arm his rockets and bombs. The resident priest would have appeared like an apparition in the rising heat waves, sweating in the broiling sun. The padre was always there when aircraft took to the skies on combat sorties. I pictured Diz giving his usual thumbs-up after the priest gave the sign of the cross, then jockeying his F-105 onto the active runway before accelerating. Easing back on the stick, his Thunderchief would have easily nosed into the brilliant midmorning sky.

The group of partygoers received word from the command post that Diz and his flight of four aircraft had made their final run on the targets they found—time for them to regroup and head for home base. But as his flight neared the Laotian border, Diz’s radio crackled. An aircraft in another flight received anti-aircraft hits, and the pilot had bailed out near them.

Dyczkowski and his flight immediately headed toward the downed pilot to begin rescue combat air control, or “rescap”—flying circles over the downed pilot to keep enemy soldiers from capturing him. Soon after arriving to help, Diz got a “bingo” fuel warning. If he wanted to continue to defend his downed comrade, he needed to find a tanker and take a big gulp of fuel.

Since tankers usually didn’t violate the North Vietnam border, Diz had to link with them over Laos. He filled his tank from the aerial gas station, broke away, and returned to the action. This counted as his 100th mission. Capt. Raymond R. Dyczkowski would join the 100-mission club a day earlier than planned, on April 23, 1966.

As soon as Diz’s squadron buddies knew he was now on the final mission of his war, the “plan” was immediately activated. There would be a parade of “follow me vehicles” on the flight line, flag waving, and ice-cold champagne—a precursor to a wild old time at the O club later that day to celebrate.

Many of the Thud pilots had a streak of black humor and would shout, “There ain’t no way!” to complete the precious 100 missions. But Diz was about to prove there was a way.

I found an empty chair off to the side, sat down, and, through the smoky haze, watched pilots talk like pilots do, with their hands. The old “there I was at 40,000 feet” routine lasted through two world wars, Korea, and Vietnam. What an arrogant group, I thought.

After about 30 minutes of schmoozing, time began to drag. There had been no news. The loud and boisterous frivolity subsided accordingly. Soon, all was quiet. The only noise was the droning of the ancient air conditioner.

Panic began to raise its head.

Nobody seemed to know what to say. The silence broke when one of the younger pilots asked why someone didn’t call the command post to find out how long it would be until the triumphant warrior returned. Why didn’t the commander think of that? I wondered.

We learned the flight was still in the air and had not yet contacted the base. We also learned the downed pilot protected by Diz’s flight was safe, and the rescue combat air control birds had been released.

With that news, some old spirit reappeared, and more good-natured bantering between the pilots returned.

Ticktock, ticktock, ticktock.

More time dragged by. Fifteen minutes seemed like an hour. More quarter hours passed. The room, again, succumbed to silence.

Another of the younger pilots finally shouted to no one in particular, “Where is he?”

His question went unanswered, and the stillness hovered over the room like the suffocating humidity outside the operations hut. The silence brought about a slight change in the squadron members’ bearing. Although far from panicky, their eyes had the look of fear, as if they were all beginning to think something had happened, but they didn’t know what.

Terry Arnold after a flight in an F-105F as a passenger on a maintenance flight check. Photo courtesy of the author.

Being the excellent trooper I was, I sat quietly in my corner chair with my camera loaded with 36 black and white exposures, hoping to document the party. But as time passed, I began to get an uneasy feeling that all eyes were slowly turning toward me, wondering why in the hell the grunt in the green fatigues was here. I asked myself the same question.

The squadron commander suggested everyone proceed to the flight line and wait for Diz. Like sheep, we all quickly piled into the squadron’s trucks and sped to the revetment area where the Thunderchiefs would park upon their return.

As we arrived, other squadron aircraft were returning from other sorties. As those pilots loudly eased their protesting fighter bombers into their stalls, the would-be welcoming party turned and scanned the horizon to the east.

“Here come some more,” someone cried. We all craned our necks to watch the flight of four F-105s break over the field for their base leg, banking left and down onto the runway again.

Diz’s aircraft was not among them. But more flights were returning.

One squadron mate who couldn’t stand still greeted each pilot personally as his plane rolled to a stop. He pleaded with them for any information on Diz. Soon, other pilots followed suit, steadily moving down the flight line to each arriving bird. The pilots raced to them, running at speeds I had never seen. I stayed behind, but from my distant vantage, I could see the arriving pilots shaking their collective heads “no” to the questions asked of them.

Soon, there was no noise. The last of the familiar whine of the Thunderchief engines had stopped.

Diz’s buddies stood in bewilderment. Many milled about, directionless.

Finally, one of the higher ranking officers who had no doubt already experienced similar disappointments directed them to drown their collective sorrow with a few stiff drinks of 25-cent bourbon at the O club.

The perplexed aviators slowly climbed into their trucks and headed across the flight line to gather around the consoling teak wood bar.

Terry Arnold at his Air Force retirement in 1987. After graduating from college in 1962, Arnold knew he had a choice to make—join the military or wait for a draft notice. Photo courtesy of the author.

I was alone. All I could see was the tail end of the last truck with an unidentified driver wending its journey down the ramp. Suddenly, the driver appeared to look in his rearview mirror and slowly pulled to a stop. He put his truck in reverse, backed up to where I stood, and stopped

To my surprise, the driver hesitantly asked me to join them at the club. For the first time, I felt that I was entering the aviator’s inner sanctum. And it stayed that way until I rotated home at the end of my tour eight months later.

We had all experienced a unique closeness that day. I knew we were all silently praying that Diz was on the ground, somewhere, and that he was safe.

My assimilation into the fraternity of pilots would have to wait a few minutes. I had to return to my office to store the camera and lock it up. I thanked the driver and told him I would catch up with them later.

Our Journalism Depends on Your Support

Loneliness enveloped me like a black cape. The stillness of the office reminded me of the squadron operations room and the flight line a short time earlier. I was frustrated. Perhaps the pilots’ black humor that “There ain’t no way” was true. Putting my film-loaded camera into its storage locker, I suddenly couldn’t hold back the tears in my eyes.

Hey, I said to myself. What’s this?

I didn’t really know Diz. I knew who he was, of course. I knew he was a pilot. But I didn’t really know him. Where was he from? Was he married? Did he have children? I wanted to ask him all those things now that I knew how much he was cherished by his comrades in flight and now, by me.

I quickly dried my eyes, left the office, got into my truck, and headed for the club. I needed some of that bourbon. I didn’t want to be alone for one more minute.

I wanted to be with my new buddies.

Postscript

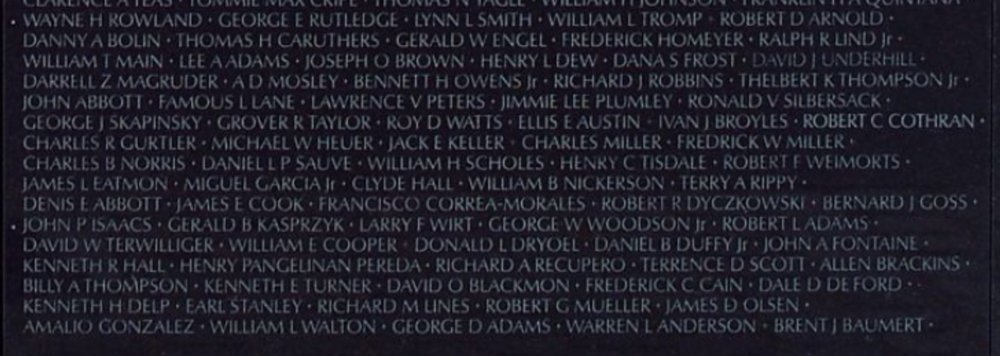

Col. Robert Raymond Dyczkowski’s name appears on panel 06E, Row 129, of the Vietnam Veterans Wall. Courtesy of viewthewall.com

The Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C., has the name Robert R. Dyczkowski etched upon it. The Air Force officially filed a Presumptive Finding of Death for Diz in 1978.

This War Horse investigation was written by Terry Arnold, edited by Kristin Davis, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Comments are closed.